The sun streaming through the stained glass windows paints the pews with light as Palo Alto High School junior Sophia Krugler takes a seat with her parents, as they do every Sunday. Waiting for the service to begin, she flips through the hymnal, and the stresses of junior year fade to the back of her mind.

“It’s a time for you to relax every week and sort of just think about your religion and block out all the other stresses of life,” Krugler said.

While religion remains an important aspect of Krugler’s life, the role of religion in the lives of young people today is changing as they grow up in a world vastly different from that of their parents and grandparents.

Among 270 Paly students of 13 classes surveyed by Verde Magazine in January, 54.0% reported not being religious*, compared to the 29.9% of the American population who consider themselves not religiously affiliated, atheist or agnostic, according to a 2014 Pew Research survey.

The fact that Paly students are nearly twice as not religiously affiliated than the average American can be attributed to location as well as age, but it is not only Paly students who are less religious. Across the country there is a trend of people moving away from religion, especially from Christianity. According to a 2014 Pew Research Poll examining the religious landscape of the United States, the fastest-growing group is made up of people with no religion and those who identify as “religiously unaffiliated.” This group, also known as “nones,” grew 6.7% while the percentage of those identifying with Christianity declined 7.8% from 2007 to 2014.

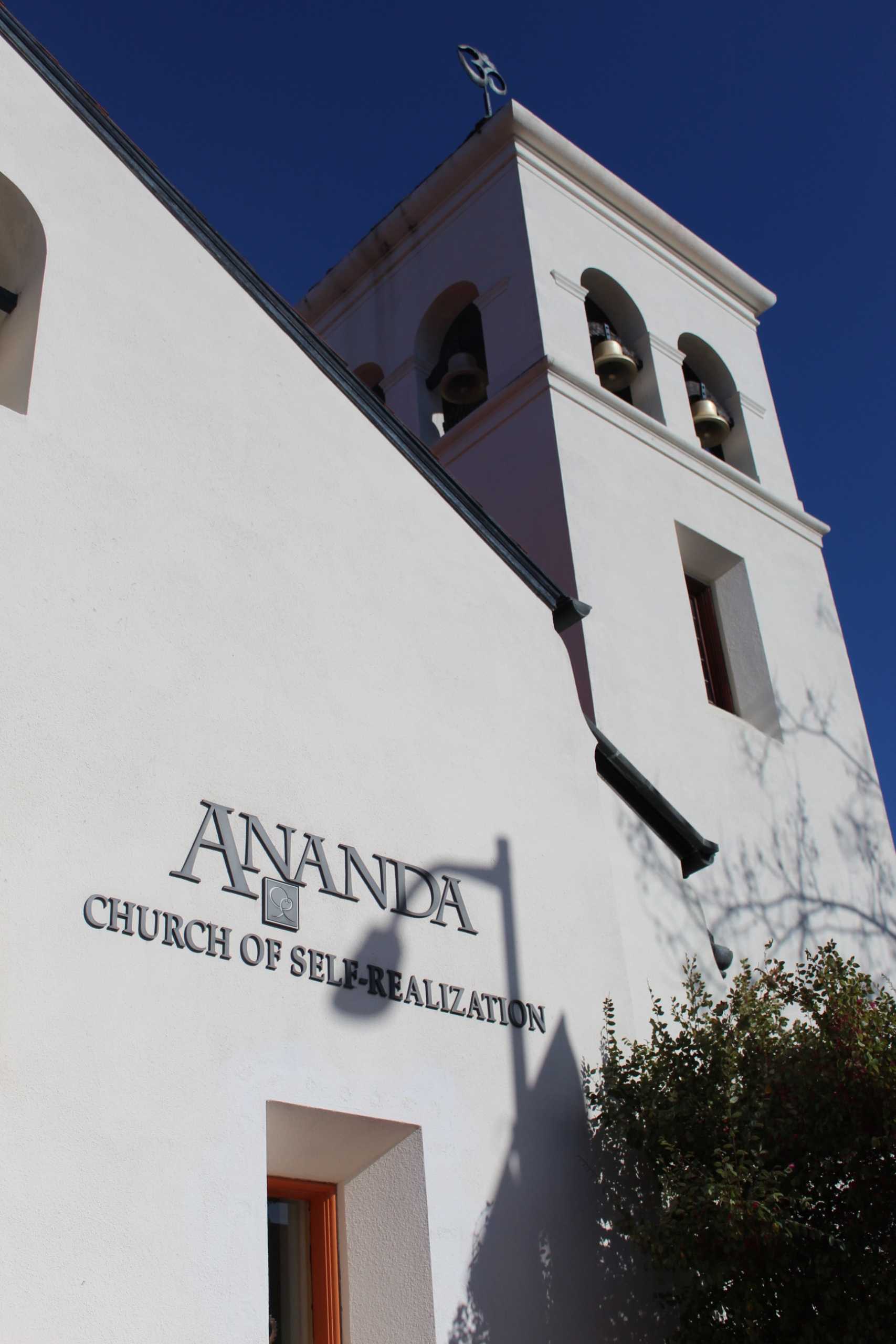

Religion in Palo Alto

The effects of these changing religious dynamics are highlighted in the closing of the local First Baptist Church. As one of the oldest churches in the area, First Baptist saw a drastic decline in congregation size from over 600 at its height in the mid-1900s to around 25 people by October when it was considering potential buyers.

“I believe we’re in an age and a place where fewer and fewer people are looking for a traditional church,” the church’s pastor, Rev. Randle Mixon, said in an interview with Palo Alto Online in October. “And while we may be one of the first of the mainstream churches in Palo Alto to fold our tent, I’d say other churches are wrestling with what we’re wrestling with.”

Paly junior Nina Hunt grew up in a religious environment with her Hindu mother and Catholic father, and attended both church and temple services on a regular basis in elementary school. But increasing commitments to schoolwork and extracurriculars have squeezed religion out of her weekly schedule.

“I’m kind of in a gray zone, I think, where I’m not like super religious, but I’m not atheist either,” Hunt said.

“[Church] is a time for you to relax every week and sort of just think about your religion and block out all the other stresses of life.”

— Sophia Krugler, junior

For Hunt, religion provides a source of community and allows her to connect with her culture. Praying is also a calming practice that allows her to destress. For these reasons, religion is still a part of her life, though she may not have the time to go to church or temple on a regular basis.

“I think that in religion, you don’t necessarily have to go to church or to the temple to practice it,” Hunt said. “You can always pray on your own at home. So if I ever feel like I’m going through a hard experience where I feel like I need to pray, I still have that time for myself.”

Behind the change

Though Hunt is one example of how teens in Palo Alto are losing touch with more traditional church-going practices, the reasons behind this shift in religious affiliations are varied, and differ from person to person.

Paly freshman Sophie Gu sees the value of religion for other people in her life such as her Christian mother, but says she feels too young to get involved.

“It’s important for some people because it is a source of light when they’re feeling down,” Gu said. “I’d like to focus on other things in my life before I decide whether or not I want to become religious.”

Barbara Pitkin, a senior lecturer in Religious Studies at Stanford University, affirmed that this is a common trend that explains why many teens or young adults are less religious than those of older generations: It is not necessarily that they do not value religion, but rather that they are not at a point in their life when they want to settle into a specific faith.

“Some [college] students might join a religious community as a way of finding community in their new phase in their life,” Pitkin said. “But most young adults don’t really get actively involved in religion until they settle down, get married and have children.”

Another potential answer as to why rates of religious affiliation are dropping is because of an increase in interfaith marriages. Pitkin explains that, as a result, religious pluralism has become more prominent — people are less committed to a single religion and therefore more likely to stop practicing.

This also explains why some religious groups, such as Muslims and Hindus that have lower rates of interfaith marriage, are actually increasing in size rather than decreasing with the overall trend.

As for younger people who are actively religious, their ideas for engagement in their religious communities are different from those of older generations, highlighting another generational distinction. David Howell, the senior pastor at the First Congregational Church of Palo Alto, observes that younger church attendees are more interested in taking action and making a difference in people’s lives than older members.

“They [younger people] will sign up and show up to go on service trips every summer, or they’ll show up to go and serve meals, or do things where they’re directly making an impact,” Howell said. “They aren’t as likely to just sit and listen to somebody talk, which is what a lot of older folks will do — they’ll come listen to speakers, they’ll come listen to sermons. It’s different at different ages.”

The way people look at religion is changing as well. According to Pitkin, people are now more comfortable stepping away.

“I think it is more culturally acceptable to say I’m not religious, or I’m an atheist than it certainly used to be in some places,” Pitkin said.

Pitkin also explains another change in the perception of religion that came about in the 1990s with the rise of the religious right wing which people saw as the politicization of religion. She says that this then pushed people away from Christianity. More recently, the exposure of cases of sexual abuse within the Catholic Church have had the same effect.

“That made people somewhat question ‘Are religions ethical?’” Pitkin said. “If those highest representatives are leading very unethical lives and the institution is not protecting children from them –– where’s the ethics there?”

Incidences of misconduct such as these are additional factors that push individuals away from religious communities, and make such changes more understandable and acceptable for the general public.

“Some of the loudest voices in Christianity … aren’t speaking words of love, they’re speaking words of exclusion. And I think that goes against our message, and that hypocrisy turns people off.”

— David Powell, senior pastor at the First Congregational Church of Palo Alto

“That [these scandals] certainly played into some people’s unwillingness to be involved in religion,” Pitkin said. “They’re real problems and real pain that some people have experienced.”

Howell says Christianity is often inaccurately portrayed, even by Christians themselves. He says the resulting misconceptions of religion, especially regarding sensitive topics such as the exclusion of the LGBTQ+ community, often drive people away.

“Some of the loudest voices in Christianity … are not the most faithful to our message,” Howell said. “So they aren’t speaking words of love, they’re speaking words of exclusion. And I think that goes against our message, and that hypocrisy turns people off.”

The future of religion

It is clear that religion is changing, but what religion will look like in coming years and how its role in people’s lives will develop is up for debate.

“I think denominational differences will keep getting less and less important,” Howell said. “You know, there’s lots of different types of churches, and lots of different ways of practicing religion. I think those kinds of things will get less and less important.”

While Howell believes religion will change with time, he predicts that it will continue to play an important role in the lives of many individuals and in society as a whole.

“I would say that religion is a very dynamic thing. I think it is still very important, even in our modern technological society, to our common life.”

— Barbara Pitkin, senior lecturer in Religious Studies at Stanford University

“I think the idea of the community aspects of it [religion] will get more and more important, as social media and technology continue to improve,” Howell said. “I think the communal aspects of people gathering to try to figure out ways to work together to make a difference in the world are going to get more and more important.”

With developments in technology and resulting greater connectivity in society, the way people regard and practice their religion continues to evolve as well.

“I’ll have students come and say, ‘Look, I can do confession on my phone. Something that I used to go into church for, I can do through an app now,’” Pitkin said.

According to Pitkin, with these changes in technology and changes in society, religion will continue to evolve.

“I would say that religion is a very dynamic thing,” Pitkin said. “It’s not static. And it’s always something that we want to keep our eye on. Because I think it is still very important, even in our modern technological society, to our common life.”

*Source: Verde Magazine collected statistics from 270 Palo Alto High School students in thirteen randomly selected English classes in late January.

RELATED STORIES

Why Paly should teach religion

Sisterhood of Salaam Shalom: Similarities make a world of difference

In the belly of Buddhism: A hidden community that prevails against common misconceptions

The orthodox paradox: Orthodox Jews reach out to community youth