“L’chaim.”

We raised our glasses, following the motions of those around us. As secular Jewish teens, this Shabbat dinner was a flurry of the foreign and the familiar. The prayers of men in kippot — brimless caps often worn by male Jews — as they faced East toward Israel, swaying and turning under the rabbi’s direction: these were parts of a different world we’d stepped into. But the other attendees exclaiming “Shabbat Shalom!”, the dancing, as the men came together in a circle, going around and around, their hands on each others’ shoulders — this all felt warm and familiar.

We’d come to this Shabbat dinner considering ourselves largely as observers of an inner sanctum, two outsiders with a camera — that is, until sundown, when all technology had to be put away — but we were treated as friends. Perhaps thanks in part to our Jewish backgrounds, we were encouraged to participate in songs, to introduce ourselves and our reporting. Alongside us, families shared stories — all in Hebrew — of their children’s experiences in the rabbi’s after-school program and struggles teaching them their parents’ native language.

Behind this gathering was Rabbi Menachem Landa, one among a Palo Alto Orthodox community intent on stitching together pieces of the local Jewish population. Speaking with him, one gets the impression that Landa exists in some other-worldly plane. In response to our questions, he rarely offered direct answers but rather began philosophizing — about God, about life. From time to time he closed his eyes, speaking with a husky gravitas, unhurriedly, as if time were infinitely replete.

Landa’s home — the site of our Friday night dinner — serves as an Israeli-Jewish gathering place where Landa frequently hosts holiday celebrations. Landa is an Israeli immigrant and part of Chabad-Lubavitch, a Jewish Orthodox movement that has unexpectedly grown roots in majority-secular Palo Alto. And yet, in contrast with stereotypical secluded religious enclaves, Chabadniks interact frequently with unaffiliated Jews, hoping to strengthen their relationships with God and their Jewish identity.

“When people ask me how many people do you have in your congregation, I say 40,000 Israelis of the Silicon Valley — that’s my community,” Landa says. “The opportunity for a Jew to feel Jewish, to feel his identity — that’s the goal.”

Although we approached this story as reporters, we quickly realized we were part of Landa’s target demographic — Palo Altan teens Jewish by heritage and culture, not faith.

We set out to write this story from the outside in — what we envisioned would be a coveted look into veiled communities of Hasidic Palo Altan Jews. But gradually, our narrative shifted. The Palo Alto Jewish community, we found, is extremely diverse, spanning from secular Israeli immigrants to tiny Orthodox communities, and yet these groups are inextricable. The definition of Jewishness straddles the line between ethnicity, culture and religion. And as Palo Alto Orthodox communities strain to keep up with progressing Silicon Valley views, they also work to bridge the divide between an older, more observant generation and one increasingly younger, more secular and less attached to Israel.

Searching for answers, we talked to six Jewish teens with different attitudes about faith, and with two Orthodox rabbis intent on bringing those teens into a more religious world.

Connecting the disconnected

Our first stop after our Shabbat dinner was Palo Alto High School, where we met with senior Naomi Levine Sporer, a member of the Reform Jewish Congregation Beth Jacob.

At school, her closest friends all come from different religions. They often talk about their varying beliefs and holidays, and Levine Sporer, too, shares stories — of honey and apples on Rosh Hashanah, of her bat mitzvah and of childishly exhilarating searches for afikoman, a piece of matzah bread traditionally hidden for children to find on Passover.

Meanwhile, a few times each week after school at a local Jewish youth group called United Synagogue Youth, Levine Sporer enters a world where her beliefs are implicitly understood by those around her. The close-knit community prays before meals, lights Shabbat candles and holds fun social activities on Saturday nights.

“It [USY] is a great way for me to keep my Jewish faith and be proud of it and … learn more about it,” Levine Sporer says. “Not a lot of people around me when I go to school are Jewish and so it’s a nice way to make friends that have something in common.”

This urge to find common ground also compels sophomore Ori Gal, a secular Jew and a member of the Jewish youth organization BBYO, Inc. The group, made up mostly of secular and Reform Jewish teens, provides Gal with a kind of kinship that is hard to find at Paly alone, he says.

“Paly sets high academic standards as well as the Silicon Valley’s fast-paced lifestyle and the focus on going to college,” Gal says. “It’s easy to neglect one’s Jewish foundations, and only view Judaism as a cultural piece of one’s life. I was definitely guilty of that.”

It is precisely students like Levine Sporer and Gal, and us, that the local Orthodox community is trying to reach. In fact, BBYO recently invited Landa to speak about Jewish history and faith.

“It’s really awesome to hear Rabbi Landa has a mission to engage Jewish teens — having one more way for Jewish teens to discover their character,” Gal says.

“The opportunity for a Jew to feel Jewish, to feel his identity — that’s the goal.”

— Rabbi Menachem Landa, Chabad of Greater South Bay

Looking to gain a second Orthodox perspective, we made our next stop at Palo Alto’s Congregation Emek Beracha, where Rabbi Yitzchok Feldman stands in many ways as an antithesis to Landa — a native English speaker, he was born into a non-observant family.

It was only as a young adult that Feldman traveled to Israel on a lark, hoping to visit a kibbutz, a communal Israeli farm, merely as an observer of an intriguing historical place. However, an almost prophet-like encounter stopped Feldman in his tracks, when a man explained to Feldman that every modern Jew has a relative a few generations removed who was Orthodox, but someone later in the family decided to disconnect from religion.

“They knew that they were making a choice,” Feldman says, relaying the words which would spark his religious awakening. “And you inherited that choice. You have no idea … what you are rejecting or what you could have.”

Feldman emphasizes that while many find the Orthodox lifestyle esoteric, for him it was largely a natural moral progression — an objective decision to choose religion as his unequivocal truth.

“I hadn’t spent all that time in the humanities talking about what’s right and wrong and what’s true and not true in order to embrace a lifestyle which was not true,” Feldman says. “There are people in any synagogue, including Orthodox synagogues, for whom it [Judaism] is a lifestyle choice and it’s not necessarily a choice between right and wrong. But that’s not the way I relate to it.”

Feldman’s goal in the midst of an overwhelmingly secular Palo Alto Jewish community is to ensure every Jew has this kind of religious agency. His kids were never forced to adhere to religious beliefs but rather encouraged to mold their own path, Feldman says. Still, they have all remained with the Orthodox community, including Feldman’s 16-year-old daughter Malka who we visited next at Meira Academy, a tiny 15-person Orthodox girls-only school on the third floor of the Palo Alto Jewish Community Center.

Growing Orthodox roots

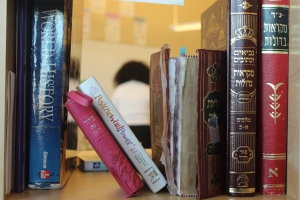

Torahs with ornate gold lettering on their tattered spines stand between biology textbooks in the student lounge at Meira Academy. A poster with the Hebrew alphabet hangs over electron orbital diagrams. A student prepares a microscope slide beneath a window adorned with colorful block letter stickers spelling “Shabbat.”

Walking into Meira, this juxtaposition can be found at every step: the observant life of an Orthodox Jew and the academic mindset of any modern Palo Alto institution.

“It definitely helps to come to school every day and be surrounded by other people who have the same values as you, who celebrate the same holidays,” Malka says.

One of 10 kids, family life in Palo Alto is near to Malka’s heart. But in the future, Malka envisions moving somewhere else — a place where the Orthodox community is met with more warmth and integrated into mainstream life.

“It’s kind of hard to raise an Orthodox family here because there aren’t all the resources you could have,” Malka says, explaining her frequent struggles even with trivial things like finding suitable clothes or places to eat. “I love growing up here — it’s amazing — but I feel like I would probably live in a more central Jewish place — maybe Israel, or even New York.”

As Malka and her friend chat with us during their lunch break at the JCC cafe, Malka explains that, as an Orthodox teen, she has more flexibility and room for individuality than some may think. Like many Paly students, she hopes to attend college and pursue a career in the field of psychology — that is, after attending religious seminary for a year post-high school.

“No one should think that being Orthodox takes you away from being able to go to college or get a great education or get a good job or … [have] a social life,” Malka says. “You’re still able to do all those things.”

Yet finding a school that combines these opportunities with a religious safe space often proves difficult. Meira is the only Orthodox high school for girls within a six-hour-drive radius — and a suitable school for boys, or for girls who feel that such a small school may not be the right fit, is even harder to find. This is what Feldman calls “the major demographic story of this community,” and it’s through him that we meet junior Danelle Tuchman, one of 14 Palo Altan teens who currently attend Jewish Community High School in San Francisco.

“A Jewish education is super important to me and my family,” Tuchman says. “My school is very much like, you practice Judaism in the way you want to and we’ll support you with doing that. … It’s just a very open environment.”

Tuchman’s commute to school? A 40-minute train ride followed by a 20-minute shuttle — a drowsy miscellany of Starbucks, music and knitting — “Honestly, if we were having this conversation after my commute in the morning, I would probably be saying very different things,” Tuchman admits, laughing.

Still, she has grown to enjoy these unique moments of camaraderie, and would rather make the commute than remain an outsider at a local public school or even at Kehillah Jewish High School in Palo Alto.

“No one should think that being Orthodox takes you away from being able to go to college or get a great education or get a good job or … [have] a social life.”

— Malka Feldman, Meira Academy sophomore

And so, our final stop becomes Kehillah. According to Rabbi Feldman, the school has weakened its Jewish affiliation and Judaic Studies offerings over the years to boost inclusivity — a move Feldman says has ironically alienated the Orthodox community that aims to preserve its traditional educational values.

Cameron Golub, a junior at Kehillah seeking a more conservative Jewish lifestyle both in and out of school, feels the effects of this diversification firsthand.

“Kehillah Jewish High School provides me with a Jewish learning experience, but not the kind that I hope to have,” Golub says. “The school is very liberal in terms of Jewish thought, and its acceptance of non-Jews has made it very hard for the school to maintain Jewish values and integrate Jewish practice.”

One of the only places Golub says he can practice his faith freely is Camp Ramah, a religious Jewish summer camp located in Ojai, California. At Ramah, Golub prays three times a day and follows strict Judaic customs such as Shabbat. However, when he returns home every autumn, these values fall to wayside yet again, overcome by academic workload and the minutiae of daily Palo Alto life.

“I am currently not living my ideal life in terms of [religious] practice, given that I live in an area where it is hard to live strictly by Judaism,” Golub says. “For the past few years I have wanted to live with a more strict practice as an adult but it all depends on where I end up and my career path.”

A Jewish journey

With Golub, our dive into the Palo Alto Jewish community had come to an end. We anticipated a story that would require covert journalistic tactics to observe a secluded community of Orthodox Jews. But the interviews and photos we gathered instead painted a portrait of an intertwined Palo Alto Jewish community, where outreach from Orthodox groups toward more liberal Jews preserved a collective religious identity.

“A lot of people picture observant Jews as men in Brooklyn with long black coats and hats,” Tuchman tells us over the phone as she walks home from the Caltrain stop, seamlessly traveling between her two worlds — an observant school and an overwhelmingly secular Palo Alto environment. “One thing I’ve learned from being an observant Jew in Palo Alto is that … we all do things a bit differently. There’s an outline that we all follow but everything else stems from family and from personal connections to God. I feel like if there were a bigger observant community people would affiliate only with people who practice in the exact same way they do, and I think that’s the beautiful part of being observant in Palo Alto.”