For Superintendent Don Austin, it was a call to arms. The most recent round of California Assessment of Student Performance and Progress results presented during the Oct. 15 Palo Alto Unified School District Board of Education meeting highlighted the age-old achievement gap widening alarmingly.

“I want to lead with my observation after being here a year that our gap between advantaged and disadvantaged is the largest and most pronounced I’ve seen anywhere,” Austin said before disclosing the data at the meeting.

According to Austin, all students are dissatisfied with the current math laning system.

“I think we have very little to lose in looking deeply here,” he said.

Austin imposed a two month deadline for educational leaders and administrators to come up with a brand new system.

“You might say ‘Well, why December? How’s that going to give us time?’” he said. “Well, how many more years of data do we need to collect before we can come back and say that ‘Here are some things we should probably look at?’”

Approximately two months later at a Dec. 10 board meeting, changes were proposed to make large-scale program reforms.

“The course offerings, based upon the Common Core Standards and the Standards for Mathematical Practice, will focus on building conceptual understanding, problem solving skills, and procedural fluency,” Superintendent of Educational Services Sharon Ofek stated in the meeting documents.

Although adjustments are still being made, the plan was praised by a number of board members, instructional leaders, parents and one student at the meeting.

However, some PAUSD parents hold opposing views when it comes to strategies for dealing with such a contentious subject.

The three most prominent changes to the math program include the plans to delane classes, revise the math placement process and update metrics to measure student improvement.

Delaning

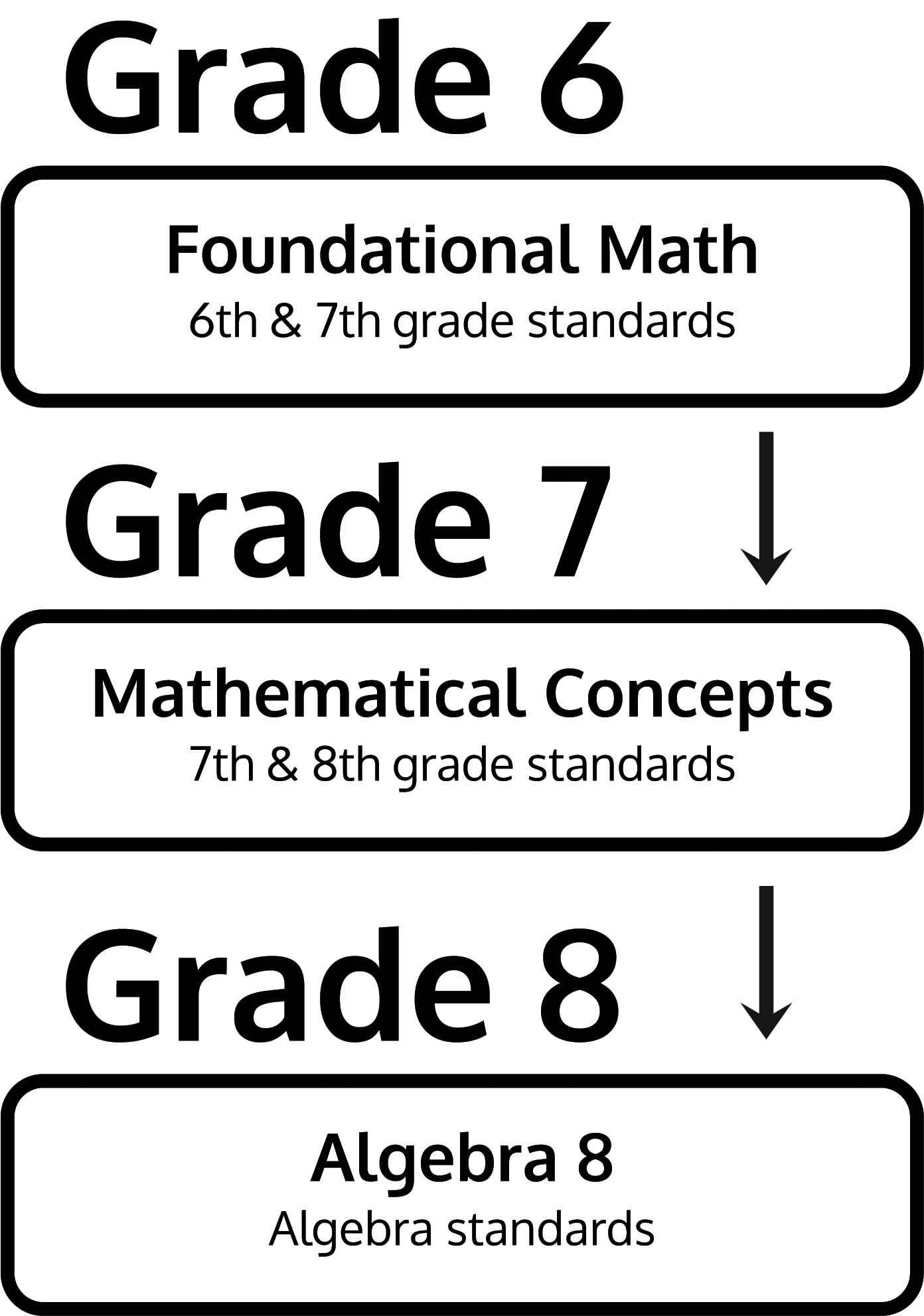

Starting in the 2020-2021 school year, the district intends to merge all students into a single math lane in seventh- and eighth-grade math classes, creating heterogeneous classrooms that would ideally prepare all incoming high schoolers to take a Geometry course having confidently passed Algebra I.

According to Jennifer DiBrienza, former math teacher and member of the PAUSD Board of Education, kids are often portrayed as the problem, instead of the system itself, and this change serves to boost student self confidence.

“Something that we as a district have missed is that if scores were low, we say ‘let’s get some extra help’” DiBrienza said. “Instead of acting like there’s something wrong with a kid, let’s change our system so that all kids feel a part of the system. I think that they are going to do better now, and the district is starting to take that approach and look at the systemic inequities that exist.”

“Instead of acting like there’s something wrong with a kid, let’s change our system so that all kids feel a part of the system.”

— Jennifer DiBrienza, Palo Alto Unified School District Board of Education member

This idea faced pushback from many parents, with the most concerned individuals representing the PAUSD parents2parents Math Advisory, an advocacy group composed of parents hoping to enhance math learning for all students. Avery Rault-Wang, a Paly parent and member of the PAUSD parents2parents Math Advisory, cited research from Prashant Loyalka of the Rural Education Action Program at Stanford University that opposes this concept.

“The speculation would be that maybe the kids feel bad about themselves if they’re in the lower lane,” Rault-Wang said. “But studies show that this is not actually a big factor. If you’re in the lane, most students don’t compare themselves against kids in other lanes. But the kids who are differentiated where you have a huge range of abilities in the same class are reminded every day that they are not as good as other students in the class.”

Suz Antink, former PAUSD Teacher On Special Assignment for math-related Common Core support, says that part of the solution will likely draw from current mixed-lane sixth grade math classes.

“Students will likely be given the option to do ‘spicy’ problems in addition to ‘mild/basic’ problems, much like the current heterogeneous sixth grade math classrooms, giving students who are passionate about math the chance to challenge themselves while also covering the basic Common Core Standards for students who aren’t as advanced,” Antink said.

Parents2parents member Edith Cohen expressed a concern with heterogeneous classrooms, in that the teacher in a classroom with a wide range of abilities will have less instruction time devoted to tailoring to every student’s specific needs.

“Secondary classes have rigid structure and significant time is spent on instruction and class work,” Cohen stated in an email. “Students already proficient can get detached and will impact others as well … It is also not a solution to those misplaced in more advanced classes due to the acceleration quota.”

Placement

Another major change that comes with revamping the math system is the process of placing students into appropriate classes. Students looking to accelerate beyond their grade level in math may only do so in sixth or seventh grade and will be limited to only one year of acceleration. Ofek explains that this ensures every student the opportunity to take Algebra I in middle school.

“Algebra is a foundational course that we value and know that it provides a really solid foundation for higher level courses later on,” Ofek said at the Dec. 10 board meeting.

While the importance of Algebra I is indisputable, Cohen and the members of the parents2parents Math Advisory stick to their opinion that students should be placed appropriately based on skill level, regardless of grade.

“They should not stop kids in sixth grade from doing seventh- grade math and have them bored the whole year,” Cohen said. “If they are ready for Pre-Algebra in sixth grade they should do Pre-Algebra in sixth grade. The right thing is to support everybody to go as high as they can, allow everybody to reach their potential, but the thinking is ‘maybe it’s easier to limit the top.’”

Metrics

PAUSD has consistently used Northwest Evaluation Association-Measures of Academic Progress testing as a way to measure a student’s progress in middle schools. However, starting in the 2020-21 school year, PAUSD will no longer be using the NWEA-MAP test, and will instead transition to the Mathematics Assessment Resource Service test.

According to the board documents, PAUSD will be transitioning to the MARS assessment, which tests students ability to apply mathematical concepts in “routine” and “non-routine” problems.

Members of the parent group collectively agree that the NWEA-MAP test should not be eliminated and say that the greater resolution offered by the test is crucial when evaluating the effectiveness of curriculum changes. “The NWEA-MAP test is superior to typical standardized tests in that a student cannot study for it, nor can a teacher ‘teach to the test,’” the parent group states on their online petition to keep MAP tests. “It is an adaptive test that quickly skips through topics that a student has already mastered and allows more accurate assessment of a broader range of topics in a much shorter sitting time.”

The greater reliance on MARS has evoked disapproval as well.

“The MARS test doesn’t tell you the content areas that the students know,” Allyson Rosen, a parents2parents member professionally trained in clinical neuropsychology, said.

Rosen is concerned that the elimination of the NWEA-MAP test will make it so that there is no way to assess the consequences of these changes.

“MAP tests have identified a weakness in a subgroup of students,” Rosen said. “It’s important to continue administering those same tests, to measure whether an intervention is effective. You can’t see change unless you administer the same test after.”

Related stories

CAASPP results spark action: Demand to restructure middle schools

Committee to deal with ongoing achievement gap