Mid-leap, a young Chinese woman bares her billowing white skirt for what seems to be the thousandth time today. Beneath her feet reads the phrase: “5,000 years of civilization reborn.”

To many of us, the image is all too familiar; every winter, billboards, buses, flyers and online media advertisements incessantly herald the arrival of the Shen Yun touring season. In this article, Verde decided to investigate the mysterious production. From a diligent advertising coalition to a religious group’s stories of persecution, one thing is for certain: Shen Yun is much more than its advertisements suggest.

Marketing madness

Despite its ubiquitous marketing, Shen Yun itself spends no money on advertising. Instead, the organization relies on networks of volunteers throughout the world to raise money and promote the show in their areas.

With volunteer contacts in 11 cities in the Bay Area alone, according to Falun Dafa’s official website, including Palo Alto, San Francisco, Sunnyvale and Fremont, it is easy to see why we so often feel like we are barraged by Shen Yun’s ads.

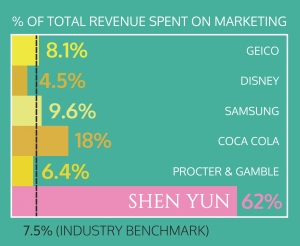

In 2017, Shen Yun-linked nonprofit groups spent at least $18.5 million on advertising in the United States, while Shen Yun’s total revenue for that year was $30 million, according to IRS tax returns compiled by the San Francisco Chronicle. That results in a marketing to revenue percentage of 62%, whereas the industry benchmark is 7.5%.

“By looking at those relative figures, my belief about Shen Yun is that they are more interested in getting their message out than generating revenue and making money,” said Eric Bloom, an economics teacher at Palo Alto High School. “My understanding is that Shen Yun has a different agenda.”

So what is the motivation behind such dedicated pro bono advertising? These advertising entities are linked to Shen Yun through a surprising connection: a religious movement called Falun Dafa that once boasted over 70 million worldwide followers,W many of whom are now dead, imprisoned or practicing behind closed doors.

Those who remain, like Mountain View resident Jianglan Xiong, have dedicated their lives to sharing their stories and practice, and spreading awareness of religious persecution at the hands of the Chinese government.

Religious roots

Falun Dafa, also known as Falun Gong, emerged from the “Qigong boom” of the 1980s and 1990s, a social phenomenon that saw an explosive rise in the popularity of Qigong, a tai chi-like practice that claimed to promote health and spirituality through specific movements and breathing techniques. At its peak, it is estimated that the number of Qigong practitioners reached up to 200 million worldwide.

Falun Dafa is a prominent submovement of Qigong first taught publicly in 1992. It focuses on moral philosophy — specifically the three tenets of “truthfulness, compassion, and forbearance,” according to Falun Dafa’s primary text, Zhuan Falun. The text holds that Falun Dafa practitioners can acquire supernatural abilities through a combination of moral cultivation, meditation and exercises.

“My understanding is that Shen Yun has a different agenda.”

— Eric Bloom, Economics teacher

Independent from the state, uber-zealous and ambitious, Falun Dafa quickly landed on the Chinese Communist Party’s radar.

“The government was worried about the threat to their power,” Xiong said. “An enormous number of people, and even some high-level government members, were practicing Falun Dafa.”

By 1998, the CCP forced Falun Dafa’s mysterious leader, Li Hongzhi, to flee to the U.S., which worsened tensions already brewing due to the state-run Chinese press’s negative coverage of the movement. During this time, Xiong was teaching as a college professor in China. She and a few scores of her students attended a demonstration demanding fair media portrayal of Falun Dafa as well as its official recognition as a religious organization. Ultimately, according to Xiong, they achieved neither.

Fed up with the Chinese government, Xiong left her job and family to come to the U.S., slipping out of reach mere moments before the CCP dramatically tightened its grasp on Falun Dafa. According to a 2002 report by the Human Rights Watch, just after midnight on July 20 1999, public security officers seized an estimated several hundred to 5,000 Falun Dafa practitioners from their homes in cities across China.

The infamous 2006 organ harvesting reports by Canadian human rights lawyer David Matas and former Canadian parliamentarian David Kilgour are believed to trace back to this date. According to the reports, Falun Dafa practitioners and other political prisoners in China were executed “on demand” in the lucrative black market trade to provide organs for transplant recipients.

To escape persecution by the Chinese government, Falun Dafa followers find sanctuary in different countries throughout the world where they are able to freely practice their religion — countries like the United States.

American ambivalence

As a nation built largely by settlers seeking refuge from religious persecution in their native countries, the United States historically has been a landmark for religious freedom throughout the world. If that’s the case, though, and considering Falun Dafa’s long history coming out of China, why are Americans not more sympathetic to their plight?

“I think that Falun Gong has some practices we would question, and that’s the really sensitive part. Is it a religion, or is it a cult? And part of that would be up to interpretation.”

— Eric Bloom, Economics teacher

The culprit may be a combination of Falun Dafa’s bait-and-switch marketing strategies and ultraconservatism — including their anti-evolution and anti-LGBTQ+ teachings.

Despite much of Shen Yun focusing on Falun Dafa’s spiritual benefits and political pleas, advertisements leave out any mention of the show’s religious affiliation. Instead, they exclusively market themselves as “5,000 years of civilization reborn” and a “demonstration of Chinese culture and tradition expressed through dance.”

“It’s not a program about the exultation of Chinese dance or arts; it’s a venue by which to spread an evangelical message — and there is nothing necessarily wrong with that,” Bloom said. “But then, why don’t you say it?”

During a majestic soprano performance by Tian Li when Verde watched Shen Yun in January, audience members were taken aback when the lyrics “Beware evolution’s deceptive doctrines/ Modern thought and ways change humankind” echoed through the hall. Meanwhile, at a Falun Dafa lecture in Switzerland, “Master” Li Hongzhi shared Falun Dafa’s teachings regarding gay people.

“When human beings overstep those boundaries [homosexuality], they are no longer called human beings, though they still assume the outer appearance of a human,” Hongzhi said. “So gods can’t tolerate their existence and will destroy them.”

Perhaps our quickness to label Falun Dafa as a cult and disregard its political pleas is rooted in one simple fact: its views stand in sharp conflict to our own.

“I think that Falun Gong has some practices we would question, and that’s the really sensitive part,” Bloom said. “Is it a religion, or is it a cult? And part of that would be up to interpretation.”

Related stories

Sisterhood of Salaam Shalom: Similarities make a world of difference

In the belly of buddhism: A hidden community that prevails against common misconceptions

Alina Taratorin: Inside the world of a competitive ballerina

The orthodox paradox: Orthodox Jews reach out to community youth