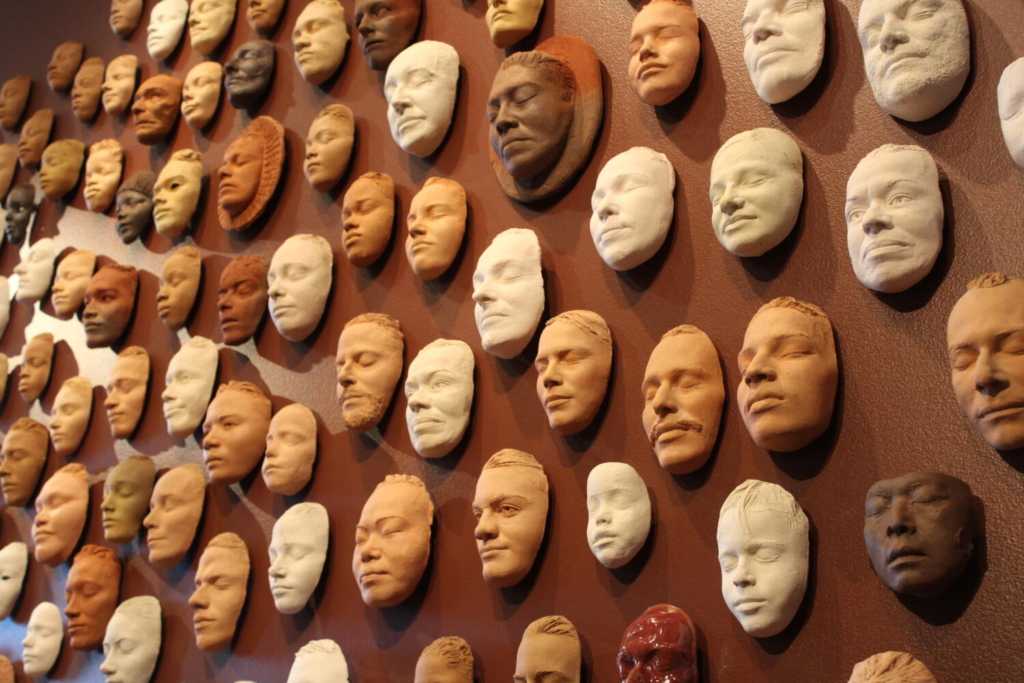

Down the marble corridor of Stanford University’s Cantor Arts Center, one exhibit captivates the eyes of many: “The Faces of Ruth Asawa.” Clay masks of 233 unique faces line the exhibit’s wall, natural light accentuating every detail. Asawa’s mask rests on the top right corner, as if watching over the crowd.

As part of its recent Asian American Art Initiative, the Cantor is displaying the clay face masks cast by the late Japanese American artist to honor her work and her contribution to art education, especially in Northern California.

Asawa is most known for her wire sculptures that experiment with color, form, transparency and shadow.

“The faces on a wall is another side of Asawa that people don’t usually associate with her work,” Aiko Cuneo, Asawa’s daughter and an art educator, said. “And everyone young and old can identify with the group of faces.”

Collaboration was essential to Asawa early on, from working on her family’s farm, learning from Disney cartoonists in a Japanese internment camp to working with prestigious European artists at Black Mountain College. While raising six children, Asawa continued to complete her art, often working early in the morning when the rest of her family was asleep. Asawa’s son, ceramic artist Paul Lanier, describes the house he grew up in as a “hub of activity.”

“The faces on the wall is another side of Asawa that people don’t usually associate with her art.”

— Aiko Cuneo, Asawa’s daughter

“When people would come over to the house, she would say, ‘Wow, you have such an interesting face! Can I cast your face?’” Lanier said.

Asawa’s guests would lie on a table, covered with a sheet, while Asawa applied plaster to their faces. She would layer Vaseline onto her subjects’ skin and eyebrows first so the plaster wouldn’t stick. The process took 20–30 minutes. Afterward, clay was pressed into the mold and fired in the kiln, resulting in incredible definition and variation in the masks.

“When we cast a face, it’s not just capturing a completely unique human being, but also a moment in time when they’re that age,” Lanier said.

According to Cuneo, when Asawa would cast the face of one of her students, a large group of students and teachers would surround her to observe.

“Even though it was one child having his face cast, the community got to watch and be a part of the process,” Cuneo said. “She liked the idea of involving the community in arts projects, giving all those who contributed a sense of pride and ownership.”

“She shared her knowledge by teaching others that they could find joy in the experience of making art.”

— Aiko Cuneo, Asawa’s daughter

Asawa believed that all students should have the same experience learning art that she did. In 1968, she co-founded a program to improve art education at her kids’ elementary school, focusing on projects with inexpensive materials, such as egg cartons, yarn scraps and flour.

“She really wanted art to be considered part of the child’s education,” Cuneo said. “We had it just by virtue of being her children and seeing it around us. But a lot of kids didn’t have that.”

Today, Asawa’s influence can be seen in Northern California, including the Ruth Asawa School of the Arts, a public arts high school she co-founded in San Francisco and a San Jose memorial to Japanese Americans who were interned during World War II. Her work has also gained recognition across the U.S. and abroad. In 2020, the U.S. Postal Service released postage stamps bearing Asawa’s wire sculptures, and in 2021, she had her first show in Europe.

“I’m totally amazed at how her story and work have found new audiences,” Cuneo said. “The path she took as an artist shows her quiet determination.”

The collaboration that fueled Asawa’s art is evident when visiting the “Faces of Ruth Asawa” exhibit.

“She shared her knowledge by teaching others that they could find joy in the experience of making art, whether they were alone making the art or together as a community,” Cuneo said. “The arts bring community together.”

INTERVIEW WITH AIKO CUNEO — Aiko Cuneo, Ruth Asawa’s daughter, and Verde staff writer Asha Kulkarni discuss the specifics of Asawa’s clay masks and the philosophy with which the late artist approached her work. “She [Ruth Asawa] was always experimenting,” Cuneo said. “She was always trying something new.”