The new era of exchange: travel programs adapt post-pandemic

Green seed pods of okra are boiled, seasoned and prepared into obe lla, the Yoruba name for a flavorful stew and staple of Nigerian cuisine. Palo Alto High School graduate Oluwatunwumi Ogunlade grew up eating it during her childhood — but when she encountered the vegetable while on an exchange trip to Louisiana, she was startled to see the same vegetable served pickled, a strange departure from the recipes familiar to her.

After graduating from Paly in 2021, Ogunlade spent a week of her summer living with a host family in Lake Charles, Louisiana.

Ogunlade’s trip was organized and paid for by the American Exchange Project, a nonprofit that connects cohorts of high school seniors to hosts across the United States. Founded in 2019, AEP is part of a new era of exchange programs.

Paly’s first year participating in the program was 2021, and Ogunlade’s cohort was the first to participate since the program was halted by the COVID-19 pandemic.

“It [the exchange program] just made me more open minded,” Ogunlade said. “There were certain conversations I had that were pretty interesting, and being there helped me empathize with why people would think certain things about the world.”

The broader student exchange program industry has struggled to revive in the post-pandemic era.

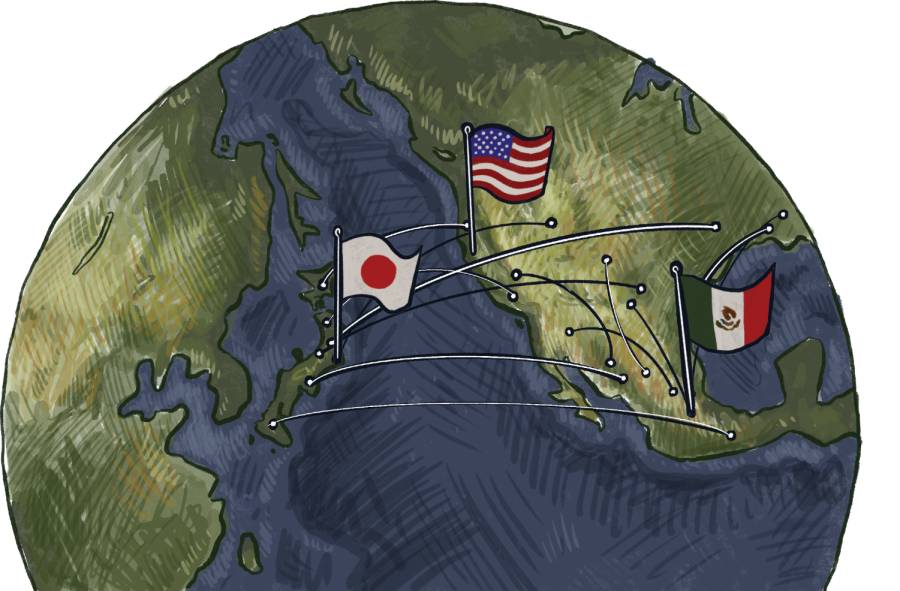

Sarah Burgess currently serves as the president of Neighbors Abroad, a nonprofit that has connected local students with host families in Palo Alto’s sister cities worldwide since 1963. When Burgess was a teenager, over 50 students (including herself) applied annually for their summer exchange to Mexico. In the past few years, she’s struggled to fill a single spot.

“Last year, I did not have any students going [to Oaxaca],” Burgess said. “I truly beat the pavement trying to find students.”

Burgess points to multiple key factors in the declining participation, from the COVID-19 pandemic to a shift in priorities in local culture. As the academic climate surrounding college applications grows more intense — especially in Palo Alto — fewer students are seeking a longer experience focused on language and cultural immersion, and many of the students who are interested in exchange programs gravitate towards more expensive for-profit programs.

“Our real competition is with paid programs,” Burgess said. “People were paying $4,000, $5,000 for their kids to go on a pre-college program … or a short period of a service project with other students [from the U.S.]. I almost wondered whether there was a feeling of safety, or that you’re getting a better product if you were paying a lot of money.”

Participants in Neighbors Abroad’s exchanges are required to cover little more than approximately $1,000 airfare and chaperone fees, along with the costs of hosting a visiting student, and the nonprofit provides additional scholarships.

Despite these challenges, this year, things are looking up for Neighbors Abroad.

A cohort of 10 middle school students will visit Palo Alto’s sister city, Tsuchiura, Japan this summer in a Neighbors Abroad program not connected to the school district.

Prior to the pandemic, 16 local middle schoolers participated annually in Neighbors Abroad’s exchange with Tsuchiura. This summer’s trip will be the first between the sister cities since 2019. Additionally, the French teacher at Jane Lathrop Stanford Middle School is working with Neighbors Abroad to plan an exchange with Albi, France next summer, and has also begun a letter exchange with students there.

Burgess credits this revival to demand from the community to continue fostering international, interpersonal relationships.

“With the Japanese exchange, we just had persistent parents who wanted to be involved in keeping it ongoing,” Burgess said.

Japan’s COVID-19 restrictions limit Neighbors Abroad from arranging a complete exchange. Regardless, Burgess sees the upcoming trip as a significant step forward from lukewarm attempts at virtual pandemic-era experiences.

Even before the pandemic, the purpose and aims of exchange programs in America have been significantly evolving.

In 1956, the Eisenhower administration created the Sister City program to foster international relationships and understanding post-World War II and to prevent another global conflict. Now, programs like AEP aim to promote intercultural unity even within the nation’s borders.

According to Paly history teacher Caitlin Drewes, who serves as the school’s AEP exchange coordinator, the program purposefully matches participants with communities significantly different from their hometowns in order to create a more meaningful experience.

“We’re politically divided, culturally divided,” Drewes said. “There are all these huge divisions in our country. So [AEP]’s goal is to help bridge that divide with relationships.”

Drewes herself has participated in exchange programs and served in the Peace Corps, and she emphasized how impactful staying with a local family can be in building intercultural connections — especially in comparison to tourist-oriented travel.

“It’s very important for people to become immersed, actually living somewhere, even if it’s only for four weeks,” Drewes said. “With a family, you’re finding out what’s important to them — you’re finding out that they eat their main meal in the middle of the day and all sit down together, or that they go for walks together, you know.”

But Drewes also said that such a fully immersive experience exchange program might not be right for every student.

“Let’s face it, it’s kind of scary to leave your house at 15 and go live in another country [or community] for months,” Drewes said. “I think it takes a really certain kind of person to do it.”

That “type of person” doesn’t have to have previous international experience, but according to Ogunlade, it certainly helps. Having lived in Nigeria until high school, Ogunlade said she is no stranger to culture shock.

“I’ve said that phrase [culture shock] over and over again,” Ogunlade said. “Because once you immigrate somewhere, it is just a part of your everyday life.”

Exchange programs can be especially eye opening for students from Silicon Valley, according to Ogunlade. In her experience, exchange trips like AEP can help open students’ eyes to the diversity of cultures across the country and world.

“Palo Alto is a very, very tiny little bubble,” Ogunlade said. “Especially if you were raised here, you don’t know how big the world is until you actually explore it, and AEP is a great way to get out of that bubble.”