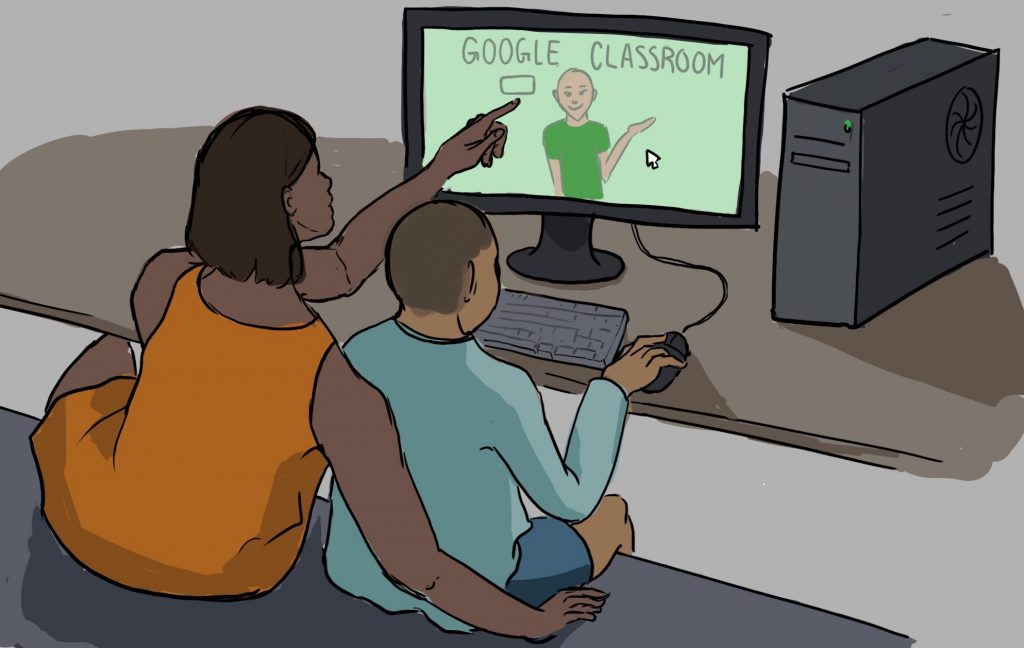

Sarah starts each day at 8 a.m. by putting on her teacher hat for an hour. She works with her elementary-aged child — who has an Individualized Education Program and requires a one-on-one aide at school — to complete the curriculum she has set for the day. They plow diligently through a series of online worksheets and activities, with Sarah — whose name, as with all of the parents mentioned in this story, has been changed to protect the identity of her child — taking note of her child’s successes.

When 9 a.m. rolls around, she switches over to her professional work until 5 p.m. This is the new normal for Sarah, who has almost entirely opted her child out of Palo Alto Unified School District learning for the duration of the shelter-in-place order. For her child, learning in a group online just isn’t viable.

“I don’t think that, on the screen with the teacher and 18 kids together … he’s able to learn,” Sarah says.

While this specific experience may be unique to Sarah and her child, many parents of children with IEPs across the school district have also found the transition to online learning challenging, and the services provided inadequate. As one parent put it, this may be a “lost semester” for some students, who will have to pick up where they left off — or even further back before the pandemic began, if they have regressed — once the schools open again.

Service cutbacks

For the portion of students with IEPs who receive services such as speech and behavioral therapy at school, the beginning of Phase III of the district’s online learning plan meant attending shorter, virtual versions of these sessions.

Audrey, the parent of a high schooler with an IEP, says that her child has not received any of their accommodations during this period of online learning. Audrey contacted the principal of the school many times but has yet to receive a response, she says.

“I feel like if they [PAUSD and the high school] cared, they would already be … reaching out to the students with special needs … and they’re not,” Audrey says. “When you reach out to the principal, or you reach out to the case manager and you get nothing, it’s kind of like nobody really cares.”

Various PAUSD and Palo Alto High School administrators declined to comment on the state of Special Education at this time. Paly Special Education teacher Christina Dias provided a written statement.

“Special Ed [Education] is following the same requirements that General Ed [Education] is doing and we are in alignment with them,” Dias, referring to the reduced service minutes, stated in an email.

“When you reach out to the principal, or you reach out to the case manager and you get nothing, it’s kind of like nobody really cares.”

— Audrey, parent

Although most parents report that they are still receiving services, the reduced minutes have had an impact on some students.

“It’s hard to argue because you know, they [services providers such as therapists] are not there, so they can’t provide the minutes,” says Kate, the parent of two children who have IEPs. “But it’s difficult because they’re not getting the overall support that they really do need to survive.”

Digital barrier

The concept of digital learning itself also poses a problem to some students with IEPs.

“For Special Ed, there are different obstacles … the executive function and the occupational skills aspects are, I think, even more exposed in this situation,” Kate says. “If you’ve got motor planning issues, fine motor issues, it’s the typing that becomes the barrier to doing your assignment.”

Eva is the parent of a middle schooler who has an IEP and who participates in the FUTURES Program, an alternative pathway for some students in Special Education.

The program accounts for students with a wide range of disabilities. However, with such a diverse group of students, Eva says, the video assignments do not work for everyone.

“For some kids it’s just completely irrelevant,” she says. “I know several parents of kids like my son whose kids are maybe less able to sit opposite to a computer — they’re just not bothering.”

The Community Advisory Committee for Special Education in Palo Alto recognizes that individual instruction is essential to the educational opportunities of some students in Special Education.

“In this unprecedented time when it is difficult for almost every family, there are definitely unique vulnerabilities for many of our Special Education students in terms of regression and trauma,” CAC District Advisory Co-Chair Kimberly Eng Lee stated in an email.

The CAC has been attending weekly meetings with PAUSD Special Education directors and communicating with members of Palo Alto’s Parent Teacher Association. They have also sent out surveys and additional resources to the families of students in Special Education.

“For the most part, there seems to be contact and support for our Secondary FUTURES kids. This two-way communication builds trust and engagement during times of crisis, and identifies student baseline and family capacity for distance learning,” Eng Lee stated.

Regression

The regression of students’ academic and social skills is of concern to some parents with children who have IEPs. Although Eva sometimes feels like giving up on formal learning for the rest of the semester, she knows that it is too much of a risk to take.

“With kids like my son, it is often two steps forward, one step back,” Eva says. “So when you’ve made those strides forward, it’s very hard to just let it go and say we’ll catch up in the fall because you may regress so much that … the six months of work that he’s lost may take you two years to get back.”

Kate also worries about regression in her children, especially in social skills.

“I think right now we’re just trying to maintain where we were in March without too much regression,” Kate says.

According to Dias, regression is not a particular concern for students in Special Education.

Missing teacher’s aides

“He [Audrey’s child] is expected to do everything that all the other students are expected to do. There’s nothing different because he’s in Special Ed [Education],” Audrey says. “So usually he has accommodations for different things, as well as the support [Special Education] class, in which the teacher would help him and the aide would help him with all of his assignments, and that’s all gone.”

Teacher’s aides can play critical roles in the educational careers of students with IEPs. Since online learning began, however, aides have been unable to talk one-on-one with students because they do not have the same credentials as teachers.

“I think it’s such … a wasted resource for some of their children,” Eva says. “And I think my son could benefit from some of his familiar aides who know his IEP goals [and] have worked with him on his IEP goals.”

“We’re trying to just kind of keep it together without too many extreme things happening.”

— Kate, parent

According to Dias, aides are available at the request of students and parents, and continue to work under the supervision of teachers.

After parents voiced their concerns about the limits on the services that aides can provide at the May 12 Board of Education meeting, Superintendent Don Austin said that the district would be waiving some of these barriers.

“Our CSEA [California School Employees Association] association is not asking for less to do; they’re asking for the opposite,” Austin says. “They’re asking to be invited to all meetings, to participate, to be those resources … [it’s] definitely part of our plan.”

At the same meeting, Board Member Melissa Baten Caswell noted that online summer school could be an opportunity to put into place some of these changes.

“It’s some additional adults who know how to work with kids with special needs,” Baten Caswell says. “How can we use them in a way that maybe helps us be more productive with these kids?”

Parent perspective

For working parents like Sarah, teaching a child with high needs while also working for eight hours a day can be stressful.

“It sounds nice that I don’t need to commute [to work] anymore, but my commute hour’s now filled with the one hour teaching for my son, so my brain has no moment to take a break,” she says. “Now I just don’t have the energy to do anything else.”

Around the world, people are taking up all sorts of new hobbies to pass the time at home, but this is not always true for parents who have to dedicate most of their time and energy to supporting their children with their learning.

“I am not bored and I’m not getting anything done. I’m not learning a language. I’m not baking bread … I’m not gardening,” Kate says. “We’re trying to just kind of keep it together without too many extreme things happening.”