“How much money is that, Mark?”

“Two dollars.”

Erika Magagna, a Special Education instructor at Palo Alto High School, asks freshman Mark Pace to hand over the change. In doing so, Mark has completed another step of his training for the smoothie business that Magagna’s class runs every fourth period.

In a spacious kitchen, other students wipe down the supplies used to make the smoothies at the back of Room 409.

“We work as a team,” says freshman Aarun Visuthikraisee, as he wipes some utensils.

After all the dishes have been put away, the work of counting the profits begins. Sophomore Sofia Lieb pulls out a black folder — she is in charge of bookkeeping for the day. Freshman Victor Cascaval counts up the money on the calculator; freshman Grace Liang sorts the dollar bills into ones, fives, 10s and 20s; and Pace counts up the change. After three weeks of training, the students are ready to begin running their smoothie business for students and staff across Paly.

“We work as a team.”

— Freshman Aarun Visuthikraisee

The smoothie business — which sells and makes beverages for a variety of classes, including Social Justice English and Science — is only one of the different services offered through the special education program. The Futures Program, a selection of classes that includes Functional Academics, Vocational Training and the smoothie business, is specifically designed for students who are not aiming to go to college because of a learning, intellectual or developmental disability. It is Paly’s solution to the issue of how they can provide for students who cannot go on to college because of these needs.

Not only that, but how can a student receive instruction that provides for all of his or her needs, while keeping broader future plans in mind? The Palo Alto Unified School District is a full-inclusion district, meaning that it must include all students in non-Special Education classes, as long as the student is learning in these classes. To keep this rule in practice, Paly has also hired two new teachers to adapt non-Special Education material to the needs of students who require a modified curriculum.

Then, the students’ schedules combine classes that prepare them for both the year ahead and the more distant future. Sometimes, it is hard to keep both these ideas in mind. Ultimately, students with such disabilities work toward the primary goal of finding a fulfilling and meaningful place in the workforce and, at large, a comfortable life.

Futures

Behind Magagna, the kitchen that houses the smoothie business is dark. The bell has just rung, leaving her spacious room devoid of the students who consider this classroom “mission control” in schedules that take them across campus and into the wider Paly community. Magagna teaches Futures, a class centered around four major categories: vocational training, functional academics, community-based instruction and inclusion in general education. The student-run smoothie business, along with a lunch-order service and a weekly cafe, comprises part of the vocational training section of the curriculum. These businesses create a real-world environment to learn in, and provide students with skills needed in the workforce.

“My main focus is to help students work on a specific set of soft skills that anyone would need,” Magagna says. “I need them within my teaching career, lawyers need them, in any job you need to be able to get along with your co-workers, have appropriate, professional behavior and initiate tasks.”

To learn these communication skills, students perform tasks such as filling smoothie orders efficiently, dealing with unsatisfied customers and developing relationships. The vocational classes also include academic components — tasks such as counting change and doubling recipes help students apply math skills to everyday life. The third component of Futures, community-based instruction, is incorporated through the lunch order business, in which students go to Town and Country and bring back lunches for teachers.

“Generally, students in the Futures program are on a track to earn a Certificate of Completion,” Magagna says. “The classes that we offer, we want them to be the most meaningful to that student life-long. A lot of times, taking Chemistry or history or Government, just the level is maybe a little bit too difficult. So we want to focus on what’s going to make them the most independent and the most successful and make them have a meaningful life after high school.”

Although the academic path for special education students is well-defined, the overall process is still fraught with complications. Even with Individualized Education Plans that are meant to address the intricacies of each student’s needs, and are supported by the diversity of classes offered through the Special Education department (even beyond Futures), it can be difficult to find an educational option that accounts for all the needs of a particular student. This can create difficulties in the relationship between the parents or guardians of the students and the school district.

Issues with Transparency

Emily, whose name has been changed to protect her privacy, has a son who is enrolled in the Futures program at Paly.

“I find the Special Education program to be restrictive for the students that are in the Futures program,” Emily says.

Her opinion stems from frustration with the fourth component of Futures, which is general education inclusion. She says the district’s policy of inclusion has not worked properly in regard to her son.

“It is very hard to find information about his class [and] about the regular education class,” Emily says. “That is something that really needs improvement. The only way to find information is to call other parents and start asking, ‘What is your son or daughter doing this year? What are they taking? How is it going?’”

Emily is dealing with a host of problems that arise when contemplating how to ensure that her son is prepared for a future after high school that will not involve college. The greatest friction occurs when communication breaks down between the district and the parents of a child who cannot self-advocate. The issue with advocacy is one of the central reasons why trying to find a plan for the future is hard — how can a parent decide for a child, even if the child cannot advocate their feelings? While Emily has run into these problems with the district, she also feels that there is some positive change happening.

“I think they are trying to do their best with the resources they have,” Emily says. “Even this year, [my son] has access to a lot of the other classes in the school, which is great. And next year, I hope that they keep adding on more and more classes for special education students with supports and material modifications.”

Emily maintains a positive outlook for her son and for increased progress in the district. However, the issue of transparency is a topic perhaps worthy of discussion so that parents can make clear-cut decisions regarding their children.

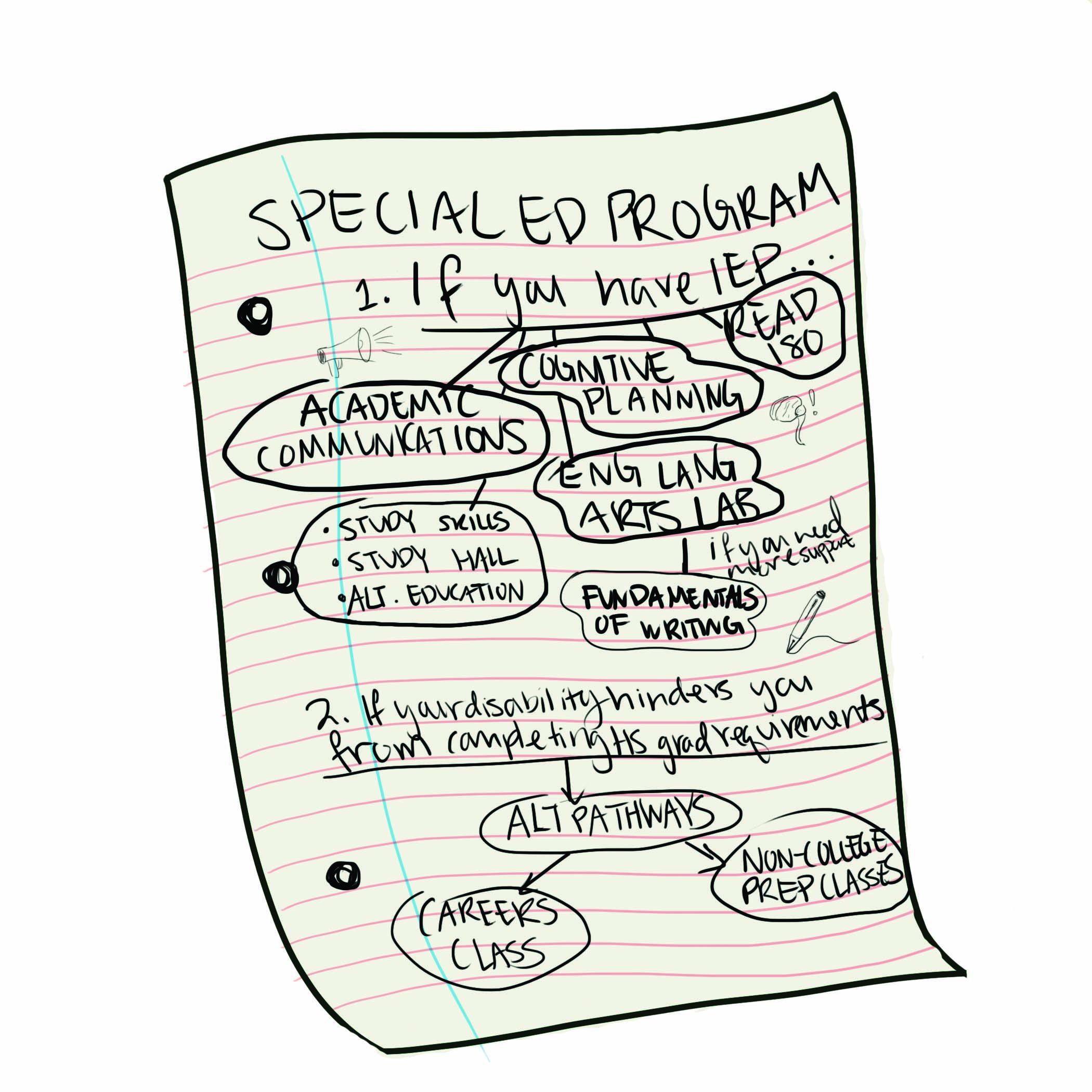

Paly offers several classes beyond the Futures Program that are meant to adapt to a Special Education student’s standard education curriculum. These courses include Academic Communications, Cognitive Planning, English Language Arts Lab, Fundamentals and Read 180. Alternative Pathways, a collection of Non-College Prep classes, is also offered for students who cannot fulfill all graduation requirements due to a disability, as well as those who can, but are interested in pursuing a vocational path after high school.

Post-Secondary

It’s a few minutes after school, and the PAUSD district office is finishing up business for the day. Amid the last-minute rush, Chiara Perry, the director of Special Education for PAUSD, stops and thinks for a heartbeat before continuing to speak in a meeting.

“When our students leave school, there is no special education outside of school,” Perry says. “We want them to be a part of the learning environment just like their peers.”

Every student must ultimately leave high school. While special education mainly provides education through high school, PAUSD also has programs designed to assist students beyond high school graduation.

“All students who receive special education services have included in their individual education plan something called an individual transition plan,” says Celia Roddy, a special education teacher with Santa Cruz City School District. “It is meant to help the student, starting when they are 16, have and reach goals for independence in their education, employment, and living situation.”

When I get a job, [Futures] will help me focus on my tasks.

— Freshman Grace Liang

PAUSD also provides the Post-Secondary program for post high school life. Legally, a student with an IEP has a right to free education until they receive their diploma or until they reach the age of 22. The Post-Secondary program provides this free education in various ways.

“They [the students] are all around the community; some of them take classes at Foothill, the adult school in Mountain View or here,” Perry says. “The instructional aide will help them with travel to that place where they are trying to go in the community.”

The Post-Secondary Program not only provides services that help students find a career path, it also provides opportunities for students to socialize, which include dances.

“It’s really fun for them to go out and spend time with students that are similar to them,” Perry says.

The Post-Secondary Program also offers an opportunity for students called Project Search, a nine to 12 month internship at Lucille Packard Children’s Hospital, where students can gain experience in fields like housekeeping and gift shop selling.

After high school, the school district also provides a transition specialist with the Department of Rehabilitation to help students find jobs. The Department of Rehabilitation provides housing and support for students who require those state services due to their disabilities. Maria Grosskopf is a Palo Alto parent whose son Johan went to high school in Concord, California. He now works at Safeway and lives in independent housing. She says that the Department of Rehabilitation is a crucial service for those who need assistance with finding jobs and housing.

“They will hook you up to a local agency that provides employment services to people with disabilities,” Grosskopf says. “Johan went first to a place in San Mateo, where they did two things. They helped him with interview practice and then they tried to get him into Project Search.”

The Department of Rehabilitation is a state-supported program; however, there are other local programs like Abilities United, Parents Helping Parents and Hope Services that provide assistance, information and day programs for people who cannot maintain a job.

The range of programs under the umbrella of the school district is quite large in measure. With the Futures Program, the standard education classes and all of the services in between, Paly has a complex infrastructure in place for its special education students. The uniqueness of a child’s needs and the ultimate goal of living a productive life intersect in different ways — but in instances similar to that of Emily, frustration arises when there is a lack of communication. Yet the end-goal for all parties seems to remain clear: to find a suitable path for the students’ futures.

To Perry, one of the biggest goals for the future in the Special Education program is to ensure that students have a sense of belonging.

“We want to make that every student feels included, that their parents feel good about [their inclusion], that any fellow student can say, ‘Hey, this student might have a disability, but they can learn just like me,” Perry says. “They can be a part of something great also.”

And Liang, sitting contently after a block period of making smoothies, is already thinking of how Futures will help her after high school. “When I get a job, [Futures] will help me to focus on my tasks,” Liang says.