As a class discussion is about to commence, Palo Alto High School sophomore Michelle Park glances up — only to be met with silence as heads hang low over tiny screens and fingers furiously tap away.

Park is among the few students on campus who remain without the one thing 95% of teenagers have according to the National Institute of Health: a smartphone.

Despite the increasing pressure to own a phone, Park has remained without the device, hoping to lead a productive lifestyle and avoid developing the habit of mindless scrolling she has observed among her peers.

“Every single second of their [students’] lives, they are … looking at their phones and scrolling through social media,” Park said.

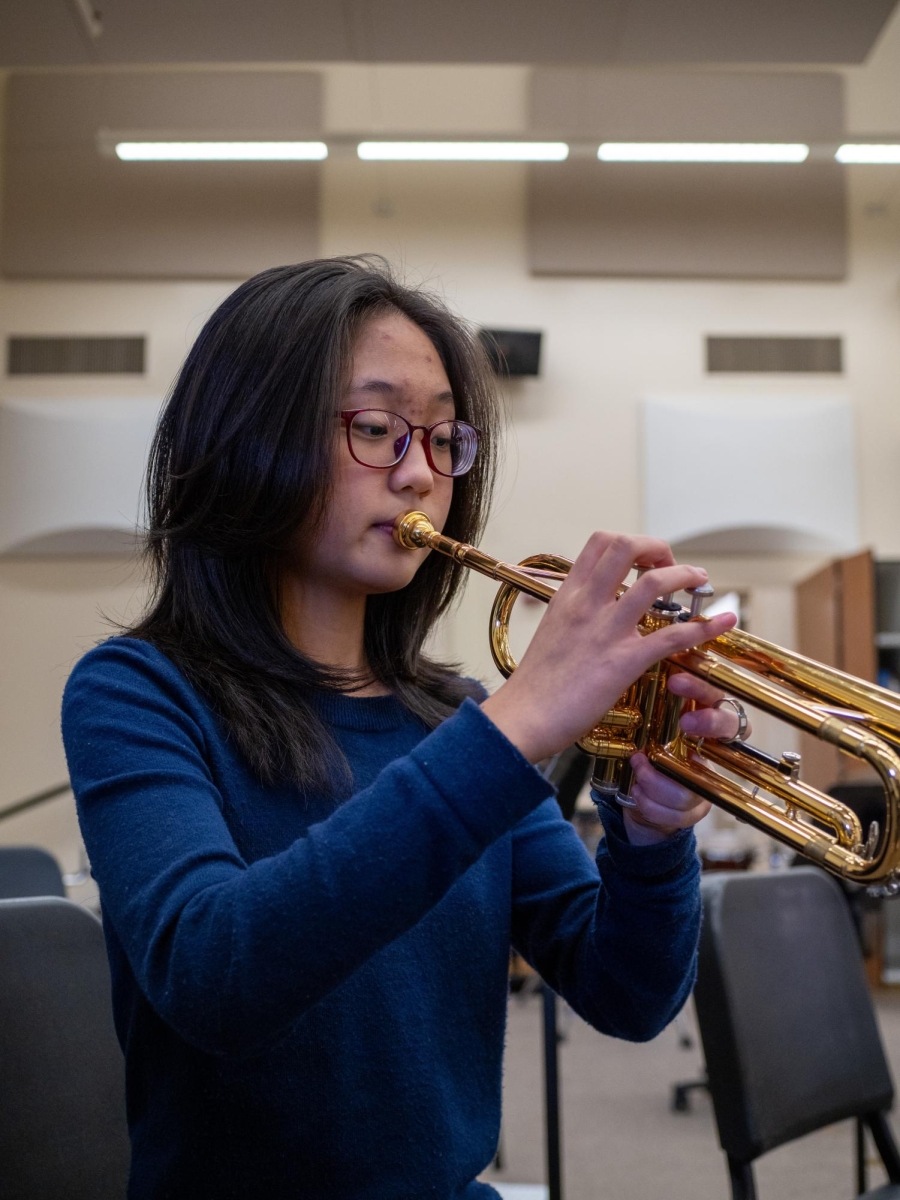

Park said that her minimal screen time allows her to focus on schoolwork and prioritize her hobbies. In place of scrolling, Park typically spends her time practicing music — an activity she strives to excel at.

“I play trumpet so I go to a lot of international competitions, and that’s because I don’t spend hours on a phone,” Park said. “If I had a phone, then I wouldn’t have as much time to play trumpet, so it [her decision to not buy a phone] is completely my choice.”

Similarly, screen time consultant Emily Cherkin, a former middle school teacher who now helps families become less tech-reliant, said that technology should be used conservatively and should not be a substitute for participating in everyday activities.

“It [technology] has the potential to be amazing, and potential to be destructive,” Cherkin said. “The three things I say [about technology use] are: later is better, less is more and relationships first.”

One of the biggest reasons why Cherkin believes technology should be limited is the distraction it poses in the classroom.

“If you didn’t have the option of having it [a phone], it wouldn’t be distracting,” Cherkin said.

In a school with such a large phone presence, Park has struggled to carry out certain assignments.

While her peers easily pull out their devices to take photos or scan codes, Park has been forced to waste time manually entering links — or consulting with her teachers to find different, low-tech approaches to assignments.

“Teachers are now asking their students to take out their phones and use them for school stuff,” Park said. “This is really hard for me because if I have to scan QR codes to access a Google form, I have to type in the entire link to my computer.”

To promote more productivity, Cherkin said she believes parents should refrain from buying their children a smartphone unless absolutely necessary, and that a line of communication should be established through “old school” devices such as flip phones.

“From my perspective, I think it’s better to wait … as long as possible,” Cherkin said. “My 12 or 13-year-old daughter doesn’t have her own phone, and she’s definitely one of only a few kids. I always recommend that parents start with flip phones … All you need is to … tell your parents that you’re running late or ‘Pick me up here’, and you don’t need the internet to do that; you just need a communication tool.”

In addition, Cherkin said that another big issue of smartphones is the increased exposure to social media — particularly the addiction that results from excessive usage.

“It’s really important to point out that social media isn’t made for kids,” Cherkin said. “The law says you have to be 13 or older to use it … but people have started using it well before 13. It’s designed to be addictive. There’s something called persuasive design … so any notification or a bottomless feed causes you to scroll constantly through any platform, no end, because that’s how these companies make money.”

Similarly, Park recalls her own experiences observing abuse of social media.

“When the teacher is talking, they [students] are browsing through … reels, scrolling through posts,” Park said. “It’s distracting for them, but it’s also distracting for the people who are sitting next to them.”

Park believes that one contribution to this misuse is the overusage of technology in school settings, and feels that schools are failing to meet the needs of students who don’t own phones.

“With AI and the rise of technology … people are starting to rely on it [technology] more for school and for work,” Park said. “If you spend more time looking at a screen, whether that be for school or other stuff, then … you just want to look at it for long periods of time and that’s how the hours go by without you noticing.”

Park said she hopes that teachers will consider this challenge moving forward and offer more paper-based assignments to facilitate the needs of students in similar situations.

However, she also understands that the transition must be gradual.

“It’s going to have to be a gradual procedure,” Park said. “This is an addiction. This is a drug. You can’t just say ‘You can’t have this.’”