Oh, you play the drums? What kind of drums?” In the eight years I have been playing Taiko, I still receive this question when the topic of musical instruments comes up. No matter how many times people ask me that same mundane question, I never quite know whether to take the extra 30 seconds to explain the art of Japanese Taiko drumming or simply say that I play on a drum set at home. But either way I always just wish I had kept quiet.

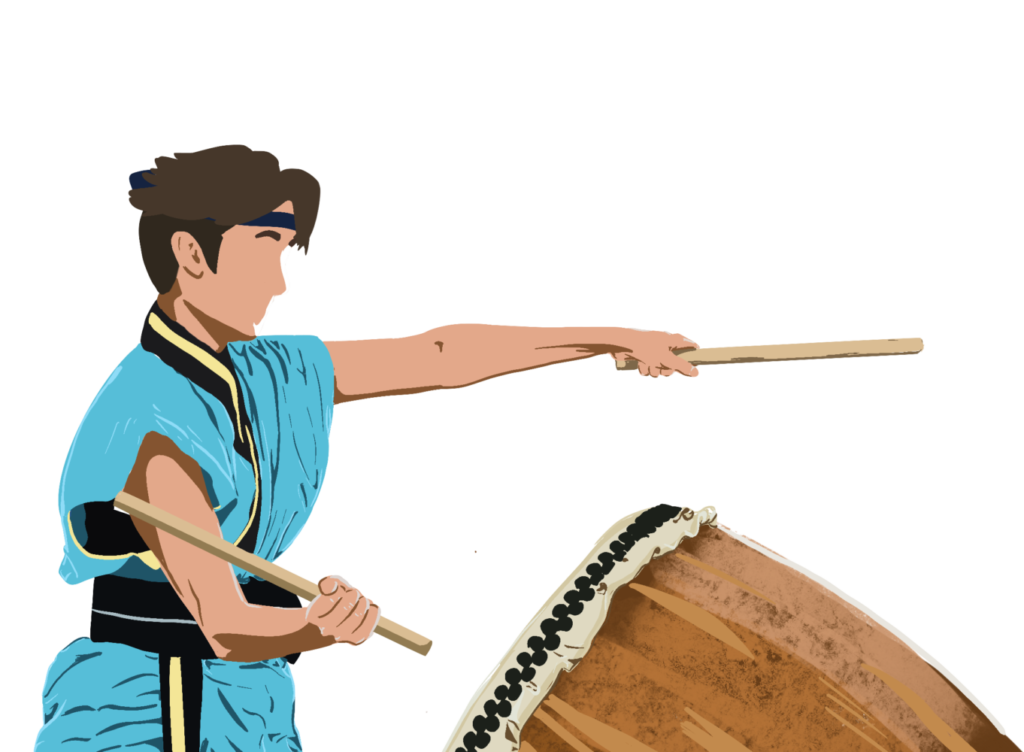

Every Sunday, for as long as I can remember, my mom has taken me to the Palo Alto Buddhist Temple. I recall being mesmerized by Taiko festival drummers who performed at the annual summer festival and scurrying up to the giant drums after the performances, excitedly peering over the ones that were almost taller than me.

However, playing Taiko began to seem increasingly dull as the people around me who played in the band or orchestra didn’t view it as a “real” instrument. My peers grew increasingly suspicious as I made excuses that “I had Japanese school” on Sundays, because taking a foreign language was far more acceptable to my private school classmates than playing a cultural musical instrument. Starting in sixth grade, I picked up violin to fulfill my middle school’s music requirement — allowing it to take over most of my time — a byproduct of which was a further disconnect from Taiko.

Taking a foreign language was far more acceptable to my private school classmates than playing a cultural musical instrument.

Story continues below advertisement

My bachi, the heavier wooden drum sticks, were no longer held with the motivation to play. In addition, an alarming majority of my fellow Japanese American classmates — and even friends — who were familiar with Taiko shunned me for playing it because they also thought that it “wasn’t normal.” These comments confused me more than hurt me. Of all people, I thought those who could relate to me would offer support when I needed it the most.

It took what felt like an eternity to rediscover my love for Taiko. This discovery was driven by the new pool of students in middle and high school who exposed me to classmates who also participated in cultural extracurriculars — for instance, Bharatanatyam, the oldest classical form of dance that originated in India. Seeing others enjoy their unconventional activities allowed me to feel confident in expressing my cultural identity as well as accepting it within myself.

With this acceptance came a change in my mindset toward Taiko. Instead of seeing its unique qualities as negative, I realized that playing Taiko was a way to connect with people who share a similar cultural background. This realization motivated me to pursue Taiko more seriously. I am currently part of San Jose Taiko’s Junior Taiko Performing Ensemble, a group that performs around the Bay Area at various events and festivals.

Instead of seeing its unique qualities as negative, I realized that playing Taiko was a way to connect with people who share a similar cultural background.

Though I originally had to explain what Taiko was in conversation, the mainstream attention that Taiko has received recently has changed the nature of their people’s reactions. Now when I tell people I play Taiko, I hear “That’s so cool!” or the cliché, “Wow, that’s going to look so good on your college applications,” as if I was being forced to do it instead in my own interests.

Despite this, I am extremely grateful that a part of my cultural identity can be expressed with less negative backlash than before. From my personal experiences with Taiko, I believe that instead of quickly forming rash assumptions –– whether it be about activities, food or customs –– fully understanding cultures can ensure a more welcoming community for all.