Vegan feminism: the philosophy that because women are treated like meat, and because meat itself is a gendered product, a feminist should reject animal products completely.

This philosophy draws controversial reactions across the board, from understanding to anger, agreement to disgust. In this article, Madhumita Gupta and Tamar Sarig discuss the pros and cons of vegan feminism, Gupta on the pro side, Sarig on the con.

“Strip Meat”: Pork, Pornography, And Vegan Feminism

By Madhumita Gupta

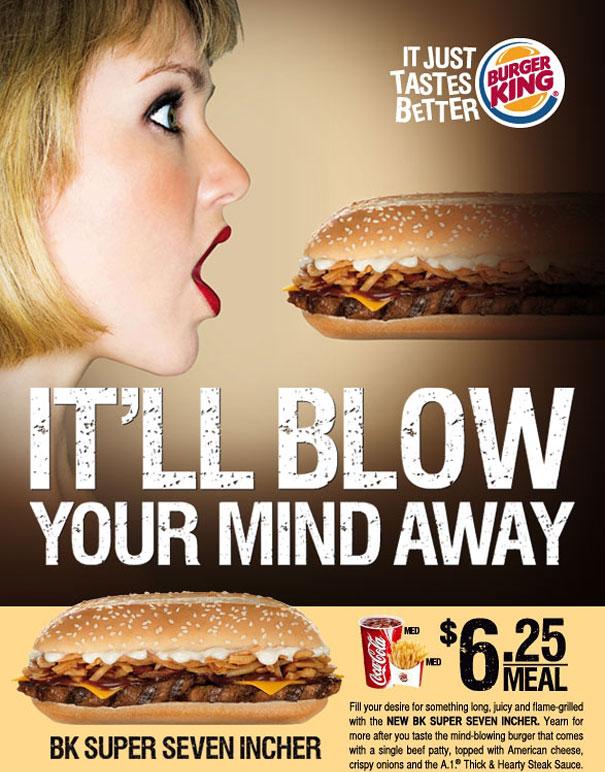

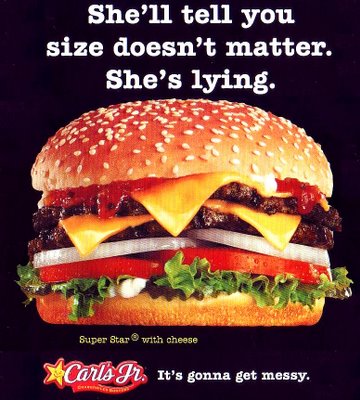

“It’ll blow your mind!” With an open mouth and brightly painted red lips, a woman gasps in surprise at a large, meat-filled burger. The implication is clear — she’s fellating the burger. This is an advertisement for the Bacon Burger, produced by Carl’s Jr., and unfortunately, isn’t the only case where sex is used to sell food. To sell chicken wings, an advertisement pictures a woman pictured naked from the waist up, with the caption, “Nibble On These!” Two recurring themes through these ads: always sexualized women, and always meat. The meat industry relies on one rule for advertising: sex sells. Which is why a vegan feminist should stand up for women by giving up all animal products.

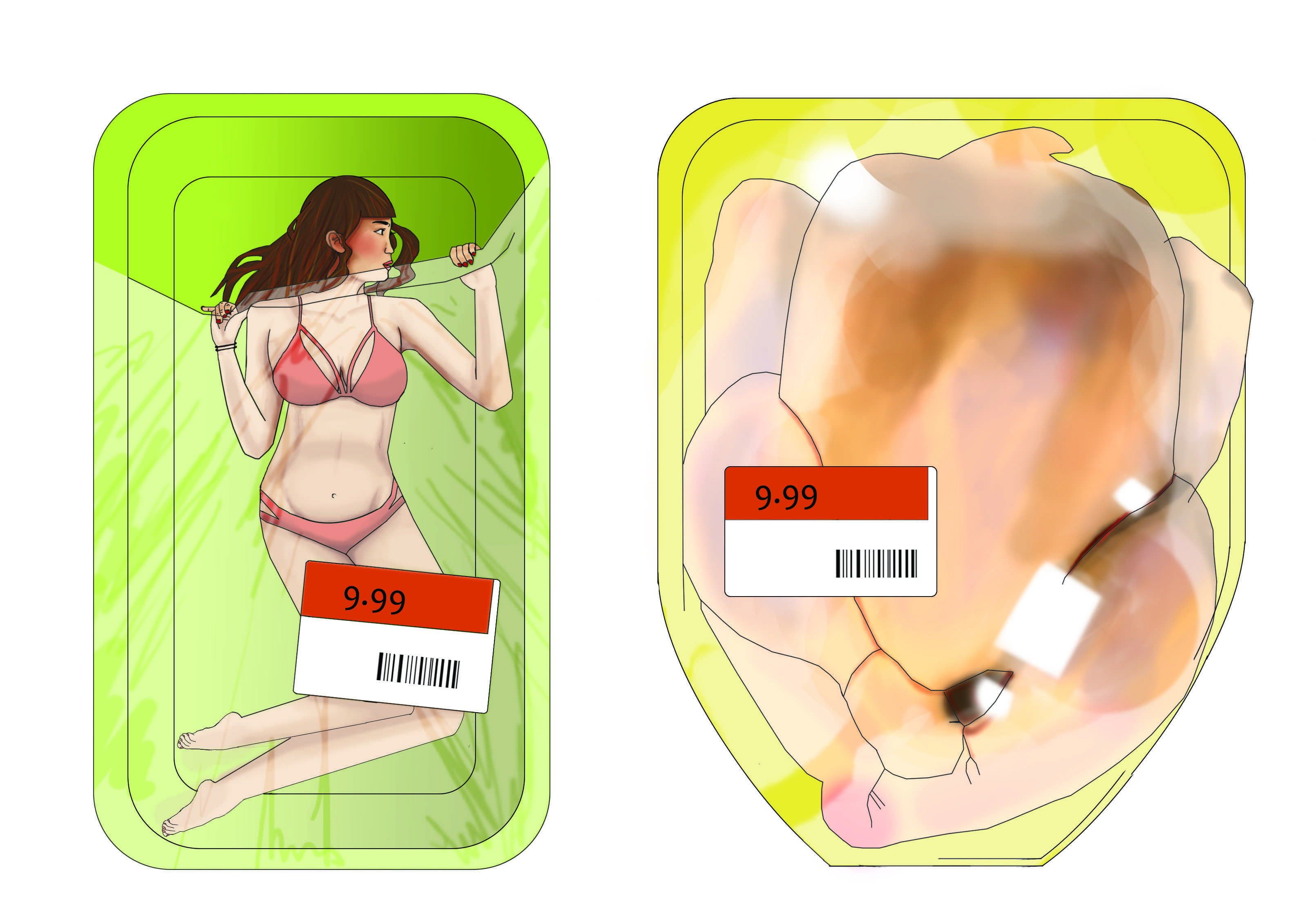

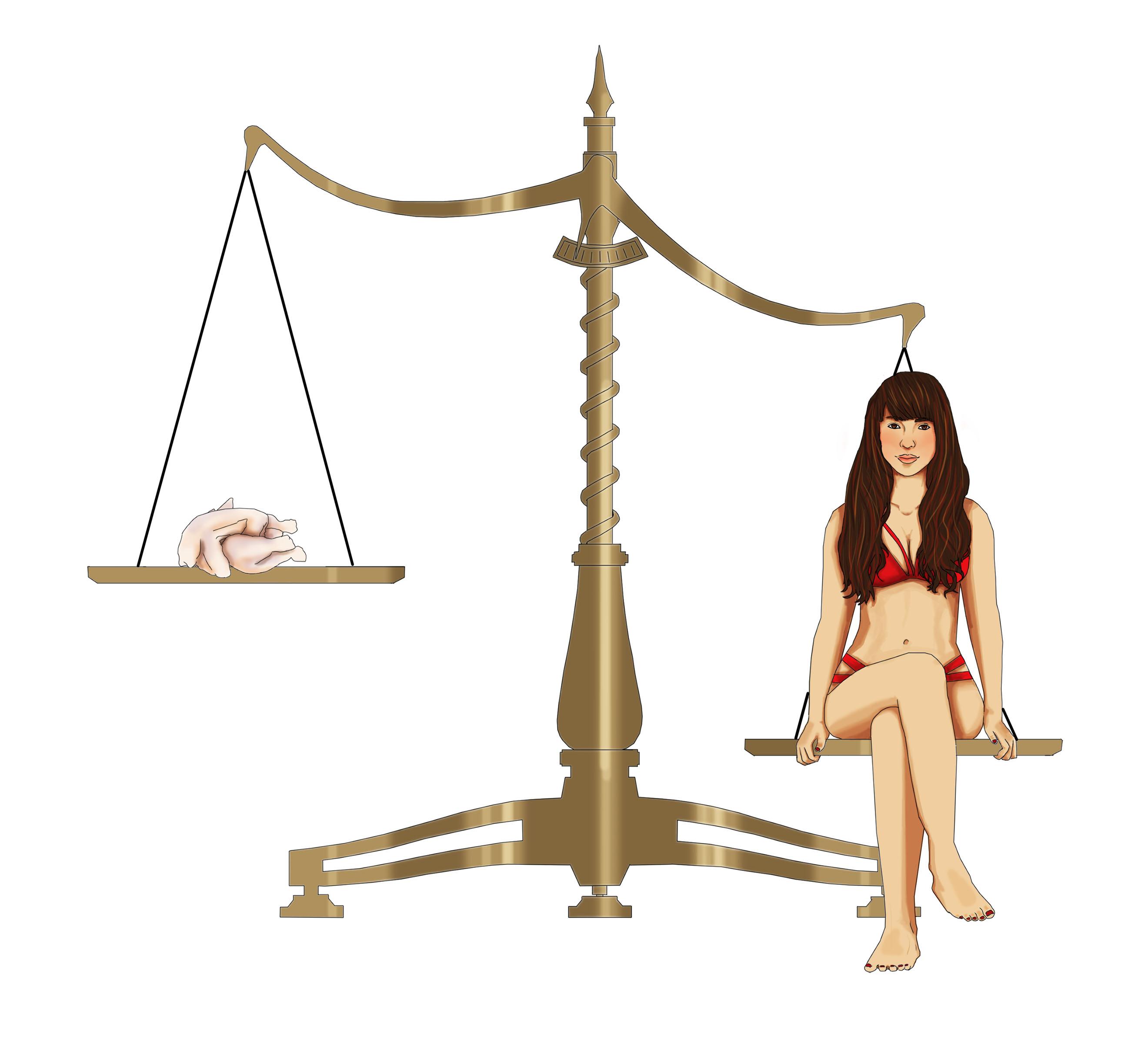

My reasons for being vegetarian have changed frequently. In fifth grade, it was because I loved animals. In middle school, it was because of the environment. After I discovered Carol Adams’s “The Sexual Politics of Meat,” the answer became clear. I am vegetarian because I am a feminist. Adams’s book helped me notice that our society treats women like meat, and I will not support an industry that uses sexist culture to sell food. In fast-food chain advertisements where supermodels wear bikinis and eat cheeseburgers, everything in the image is meant for consumption. The model’s body is carved up by the viewer — lips, legs, breasts, butt — the same way a chicken is carved for eating — wings, legs, breasts, thighs. The woman and the animal become a sum of parts. Neither is understood as a being with thoughts, an individual with feelings.

Meat eating is also inherently connected to power. In Adams’ book “Defiant Daughters,” multiple women talk about their experiences with vegan feminism, and a common theme runs throughout — when a woman experiences sexual harassment or sexual violence, she has the strong desire to eat meat. Why? Because she feels powerless, and the best way to feel empowered again is to exert unnecessary force against someone who can’t talk back. Because meat means power, and meat is considered “manly”. Meat platters are advertised as a “man’s plate.” The Sausage-Bacon Burger from McDonalds is advertised as “Sausageness. Baconess. Manliness.” The idea that meat is for a man makes no sense until we see advertisements for “Rosie the Organic Chicken” and pigs dressed up in high heels and jean shorts, spreading their legs, advertising “strip meat.” By rejecting meat, I am opposing the idea that empowerment must come from expressing dominance over another species.

Dairy products and eggs also fall into the category of products to block, because they count as “feminized protein,” or protein that has been taken from female animals by manipulating their reproductive systems for our gain. Chickens are artificially inseminated to provide eggs. Cows are given reproductive hormones to force extra milk production. Even though they are produced without killing the animals, dairy and egg requires a kind of sexual slavery of female animals in particular, which is why vegan feminists avoid them.

Sentient beings should not be treated as objects. Animals are not objects designed for consumption, just like women are not objects created for pleasure. Meat plays a key role in the gender imbalance of power, so you cannot reject the latter without rejecting the former.

An Omnivore’s Defense: The Ethical Failures of Vegan Feminism

By Tamar Sarig

I grew into my feminism so early that I may as well have been born burning a bra and quoting Simone de Beauvoir. For as long as I can remember, I have been passionate not only about women’s rights but about the way women are viewed in society, the standards to which they are held and the ways in which they are so often devalued. So why does the concept of vegan feminism — an ideology that seems, at face value, to be a reasonable extension of the fight for gender equality — strike me as such a blatant slap in the face to the values of the movement I hold so dear?

For starters, it rests on a central tenet that doesn’t hold up to much logical scrutiny. Assigning a complete moral equivalence to all living things is misguided at best, and leads to some uncomfortable results when stretched to its logical conclusion. Feminism, a movement based on equality between human beings, does not necessarily demand equality between all living things for a very simple reason: human rights and animal rights are separate conversations, fraught with different moral issues that can’t be condensed into the same neat ideological package.

Furthermore, the vegan feminist insistence on interspecies equality, while a touching and admirable belief, collapses under pressure. How do we decide which organisms are covered under our belief in equal rights? Any definition is arbitrary, and necessarily reflects an uncomfortable but undeniable human belief: that some living things, no matter how much compassion we may have for them, are simply not equal to us.

In most real-life situations, we are capable of recognizing that social justice does not apply with equal fervor to all living things. Even the most devoted of animal rights activists would bristle at the suggestion that the meat industry, which has certainly killed more living things than Adolf Hitler ever did, is an atrocity comparable to those of the Holocaust. And when faced with the choice between saving a child or a cat from a house fire, the vast majority of rational people would rescue the human being before the animal.

But the insistence that feminists renounce all animal products in order to remain ideologically consistent is more than just logically flimsy. More perniciously, it devalues women, placing us squarely on the level of livestock — a place we have fought for centuries to rise from. No, a human female is not comparable with a non-human animal. A woman lives, thinks, feels, experiences the world, contributes to society and suffers from oppression in ways that her nonhuman counterparts simply do not. And the movement formed to fight for her, to elevate her to the status of her fellow human beings, is right to see her as a special case, to fight for her without treating her as if she were no different from a dog, a squirrel, a spider.

That’s not to say, of course, that I don’t find the abuse of animals to be unspeakably horrible and repulsive. The same values that infuse and strengthen my feminism — compassion, empathy and a drive to improve our society — lead me to care deeply about the fair treatment of other living things. Without insisting that human women are on par with nonhuman animals, feminists can extend our passion for a more just world to fight against animal cruelty. The consumption of animals need not involve torture or suffering.

By all means, if your conscience demands it, extend your belief in equal rights to animals and go vegan. I may not join you, but I’ll respect the strength of your convictions. Just don’t try to stretch feminism — a movement concerned with human rights and the inequality of human society — to cover every aspect of your personal moral code. Change your own diet if you feel you should; luckily. feminism leaves you plenty of room for personal choice.