Self-styled “foodpreneur” Nicholas Phan recalls his trip across the Atlantic Ocean on a visit to Los Angeles late last year. As founder of Biju, a London boba tea store that he says strives for accessibility and quality tea, Phan found himself in an environment where boba was considerably more mainstream.

“There are a lot of Asian Americans in the West Coast, and a lot of them love boba,” Phan tells Veritas in a Skype conversation. “It’s more popular there, and it became more popular a longer time ago than it did in the U.K.”

The presence of boba stores like Teaspoon, ShareTea, Pop Tea Bar, Gong Cha, and T4 in Palo Alto alone help demonstrate Phan’s point. Paly junior Angel Trach believes that the drink’s popularity is due in part to the toppings paired with it.

“If you think about most drink stores here now, like Starbucks and Peet’s, you don’t add toppings to your drink,” Trach says. “The fact that you drink but you’re also chewing is kind of interesting.”

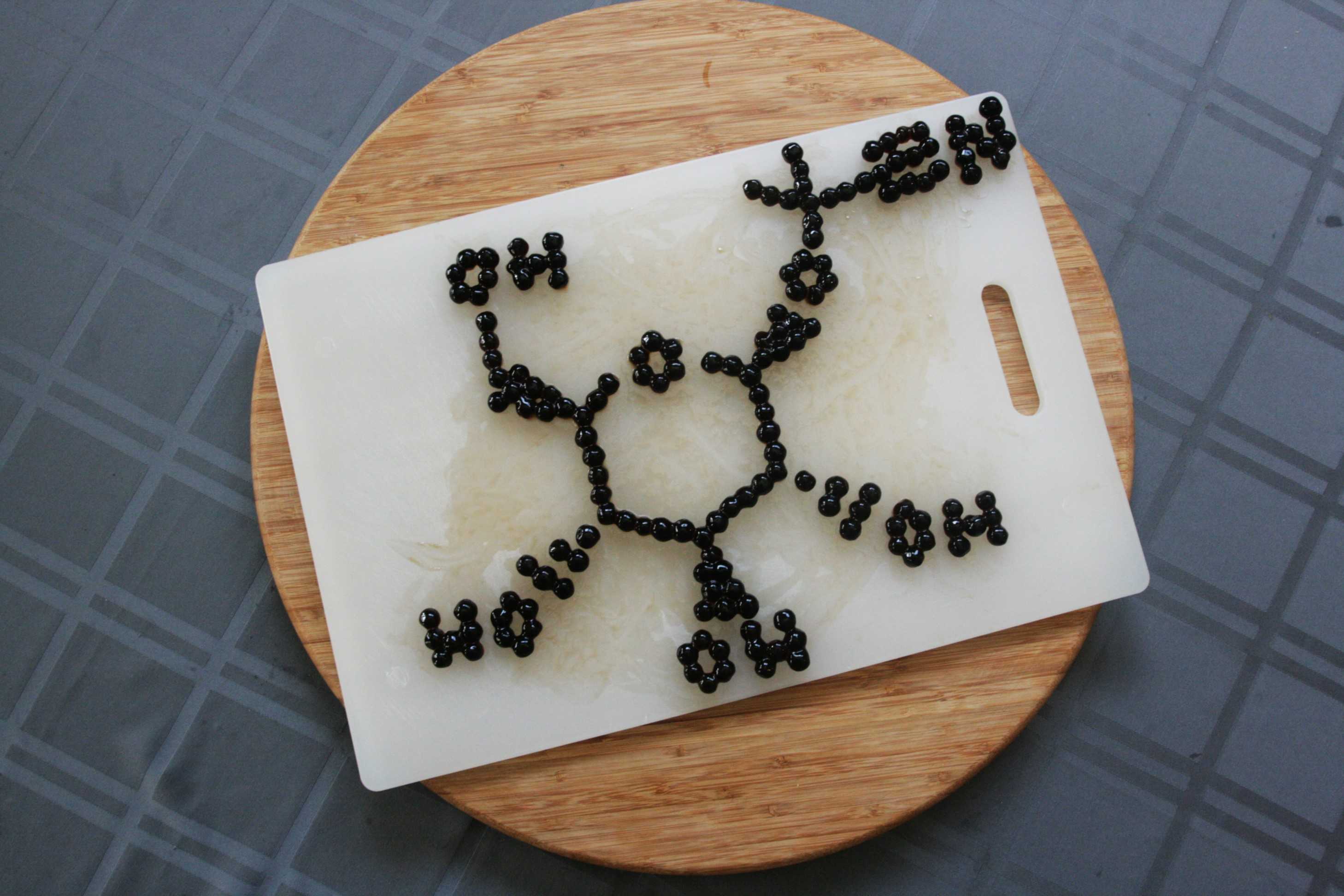

Tapioca pearls remain the most common topping on boba tea. They’re so common, in fact, that tapioca pearls are often merely referred to as boba. But do Paly students know what they’re made of, or how they get their unique texture? Veritas sought to answer these questions and hopefully satisfy curiosities along the way.

Getting the ball rolling

To fully appreciate the chemistry behind the drink topping, one must start from the beginning. Pearls are derived from cassava (scientific name Manihot esculenta), a woody shrub found near the equator. The cassava plant is tuberous, meaning that it contains a thick, edible root (think yams) which is harvested. The root is processed into a flour-like starch called tapioca by peeling and washing it, grinding it into a wet paste, and then spinning the paste in a centrifuge, as described by the National Institute of Health in a 2011 report.

“It [boba] is basically a carb like pasta, except this pasta, this carb, might be coated in sugar.”

— Nicholas Phan, founder of Biju

It’s worth noting that the cassava root contains dangerously high concentrations of linamarin, according to Dimuth Siritunga and Richard T. Sayre of Ohio State University. Linamarin is a cyanogen that produces hydrogen cyanide in the digestive system. Careful processing of cassava is crucial, and the presence of linamarin “can be reduced to safe levels by maceration, soaking, rinsing, and baking” it, according to Siritunga and Sayre in 2003. Having gone through most of these processes, tapioca flour loses any toxic properties its original form might have had.

But not all pearls are created equal, according to Phan, who adds that the chemical makeup of tapioca pearls varies from brand to brand.

“Some people might go for the cheapest ones [pearls],” Phan says. “We go for quality. But there are some I’ve seen where they have a lot more additives, a lot more preservatives, a lot more artificial ingredients in it.”

Phan cites potassium sorbate as the most commonly found artificial ingredient in tapioca pearls, but it’s not the only one. A standard 8.8-ounce bag of Wufuyuan tapioca pearls, for instance, contains guar gum, a common thickening agent, as well as the preservatives sodium diacetate and sodium dehydroacetate. Caramel provides coloring for the black variety, while rainbow pearls rely on more artificial compounds like Yellow 5, Red 40 and Blue 1.

Turning up the heat

Trach, whose parents formerly owned a Sweetheart Cafe in Milpitas and now have locations in Oakland and San Francisco, says cooking tapioca pearls is a straightforward process, whether you’re cooking a batch at home or at Teaspoon, where Trach once worked.

“First you order the boba, and you boil it for … between one and a half hours and two,” Trach says. “Depends on the shop. And after that, you wash it and drain it, and then you add the sugar.”

It might be difficult to imagine the iconic jelly-like pearls coming from boiled starch, but in truth, there is no compound more suited for the task. The key lies in the phenomenon of starch gelatinization. Put simply, it’s the process by which starch releases its contents in water when heated, creating a thick, soupy mixture.

Just as a balloon eventually pops, starch granules break apart at a high enough temperature, allowing starch molecules to mingle and form a layer of moist gel.

Guy Crosby, a food scientist, Harvard professor, and author of The Science of Good Cooking, explains starch gelatinization in greater detail on his website The Cooking Science Guy. According to Crosby, all starches are primarily made of the compounds amylose and amylopectin, which link together to form microscopic starch granules. Boiling provides a combination of moisture and heat, causing the granules to expand and absorb water “like blowing air into a balloon.” But just as a balloon eventually pops, starch granules break apart at a high enough temperature, allowing starch molecules to mingle and form a layer of moist gel.

The process affects all starches, not just tapioca: It’s the reason why wheat flour or corn starch added to butter makes a thickening roux, and why short-grain rice comes out sticky when cooked. If that’s the case, however, then why is tapioca the only starch that becomes chewy when gelatinized?

Unlike other foods, tapioca is a tuber, not a grain, meaning it has a below-average amylose concentration. This, in turn, lowers the temperature at which tapioca starch gelatinizes, allowing the boiling process to have a more pronounced effect.

Mission nutrition

Nutritionally, tapioca pearls are in a unique position. As a product of starch, tapioca contains a high amount of carbohydrates. However, the formation of tapioca pearls requires heavy processing which reduces its nutritional value.

“It’s basically a carb like pasta, except this pasta, this carb, might be coated in sugar,” Phan says. “In my mind it’s between … one hundred, two hundred calories for one serving of boba.”

2009 study in Comprehensive Food Science and Food Safety describe cassava as an “energy-dense food,” containing more calories per area of crop harvested than four other staple grains, but found it lacking in protein and dietary fiber compared to potatoes, wheat, and rice, and comparable in fat content. On top of that, the dense energy content of tapioca doesn’t do much for it in terms of flavor, leaving sugar to do the rest.

“We like to sweeten it with something, otherwise it doesn’t taste of anything,” Phan says.

“The sugar differs depending on the store,” Trach says. “I remember my parents’ store was [used] just white cane sugar, but at Teaspoon they use something different.” Trach declined to identify the sweetener, citing uncertainty about the information she was allowed to disclose as a former employee.

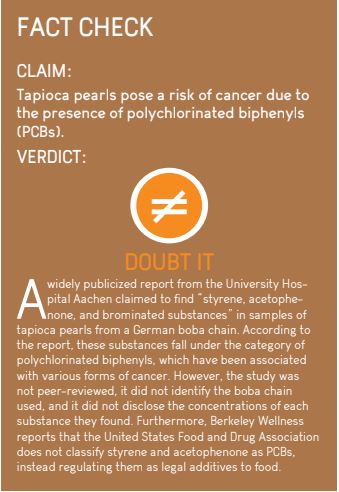

While tapioca pearls themselves don’t conclusively pose a health risk, it should go without saying that boba tea is best enjoyed in moderation.

“Boba drinks are considered a dessert,” Trach says. “Tea you can have on a daily basis, but boba itself? Probably not.”

Correction: in the print edition of this story, Angel Trach’s parents were described as currently owning a Sweetheart Cafe in Milpitas, when they had actually sold the store and opened in two new locations. Additionally, the name of the city was incorrectly spelled as “Milipitas.” Veritas would like to apologize for these mistakes.