Chop. Chop. Chop. The rhythmic sound of my mom dicing green onions wakes me. It’s earlier than usual, but I get out of bed easily, my heart full of excitement for the day ahead: Lunar New Year, or Seol in Korean.

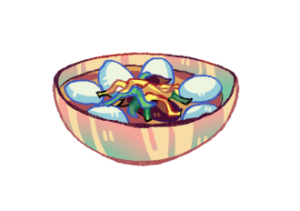

In the kitchen, my mom is sprinkling tiny cylinders of green onions into a pot of tteok-guk — a traditional Korean soup rich with dime-sized rice cake slices and dumplings — and always eaten to celebrate Seol.

I hurriedly wake my dad and my sister, and we set the dining table with spoons, chopsticks and plates of kimchi and seaweed. When the tteok-guk is finally ready, we sprinkle seaweed into our bowls, ladle the hearty broth out and drink a spoonful of soup together. Mmm. A perfect first meal of the year.

In Korea, people say that once you eat tteok-guk on Seol, you have finally gained a year in age. My sister and I used to eat several bowls in hopes of getting older faster — looking back now, I wonder why we wanted to grow up so quickly. Although the soup burns the inside of my mouth, the taste of a year’s worth of maturity is delicious.

I remember what Lunar New Year used to be like when I lived in Korea. We would drive to my grandparents’ house a day or two before the holiday. On new year’s morning, we would get dressed in hanbok, Korean traditional clothing, and do a new year’s bow (sebae) to my grandparents, uncles and aunts, who would make me well-wishing remarks for the new year (deok-dam) and give me money to fill my money pouch.

Sometimes, I wonder if I even have the right to say that I celebrate Lunar New Year.

Then, I would prepare food — plates of side dishes, bowls of rice and soup, traditional Korean desserts and makgeoli (rice milk alcohol) — with my grandma, mom and aunts always there to provide me with new cooking tips. Later, we would set up an altar for my deceased relatives with their favorite dishes and bow to them. There would be plenty of food for all of my visiting extended family, and we would gather around the table to eat together, my uncles complimenting me on my cooking (to which I would always laugh: we all knew my contributions to the meal were limited).

In the afternoon, we would play traditional games. My favorite was yutnori, a board game where one would throw four sticks and move a collection of markers based on how many sticks flipped over. Each family would form a team, and my cousins and I would cheer for our parents until late at night — the younger members of the family would fall asleep and those who were able to stay awake would continue the celebration through the end of the night.

Since I moved to Palo Alto, my hanbok does not fit me anymore. In my everyday jeans and hoodie, I do the sebae to my parents with my sister; I am embarrassingly rusty and nearly fall off-balance. My parents, laughing at our attempts to suddenly show respect, say a few words of well-wishing and hand us a few dollars. For my relatives, we compromise by bowing through a video call the day before — since Korea is nearly a day ahead — but I wish I could give a proper bow, receive well-wishing remarks in person and earn the prized new year’s cash like I used to.

I’m not in Korea, so I cannot perfectly follow the traditions, but I can still celebrate in my own way.

A day after my relatives in Korea celebrate Lunar New Year, my mom buys or prepares a few dishes along with her signature tteok-guk, but just enough so that there will not be any leftovers to throw away. In Korea, there never seemed to be enough food to match the energy of my grandmother’s house, filled with love and extended relatives, no matter how much we made. But in Palo Alto, my excitement for the New Year’s day is annually disappointed by my house that feels void of relatives, food, noise and energy.

Sometimes, I wonder if I even have the right to say that I celebrate Lunar New Year — I only follow a fraction of the Korean traditions I would follow if I were in Korea. My relatives and the hum of excitement in the house are missing.

Yet, I don’t think I even have to determine how appropriately I am celebrating. I’m not in Korea, so I cannot perfectly follow the traditions, but I can still celebrate in my own way. This is the way over a million Korean Americans have modified the traditional Lunar New Year to connect with our culture.

Maybe that is why tteok-guk is still one of my favorite dishes — it is served with memories of Lunar New Year and my relatives, but I also see my roots, my culture, my ancestors, my childhood, my family and my future in its steam.