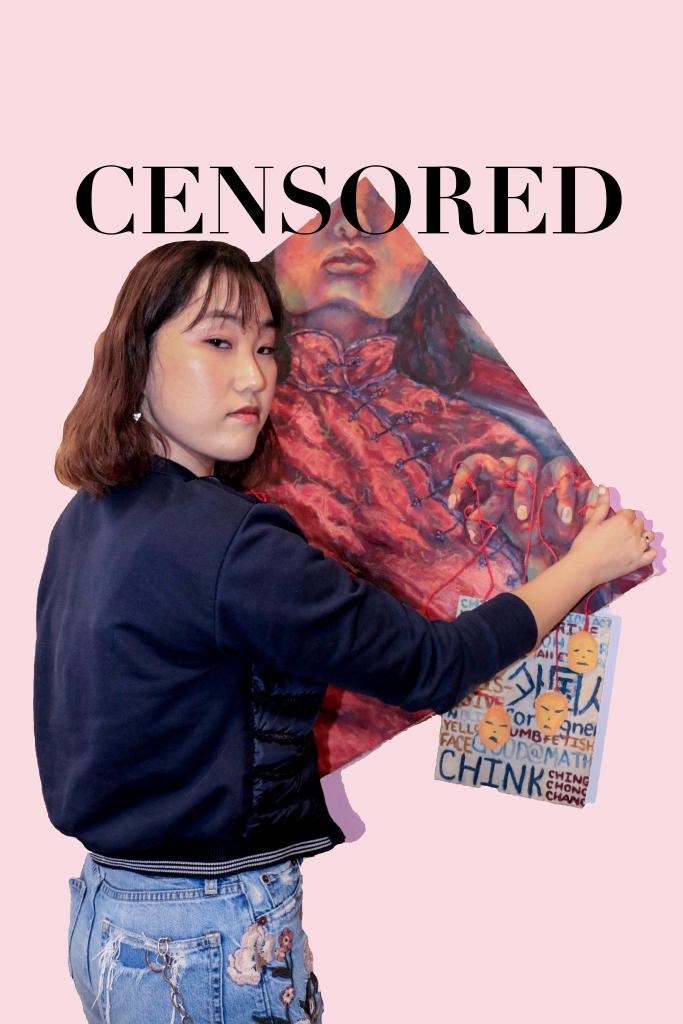

EDITORS’ NOTE: While we recognize that racial slurs such as “ch-nk” represent the institutionalized oppression and systematic disenfranchisement of minority groups, we believe that its use is essential to the of discussion of purposefully provocative art in “Drawing a Fine Line.” According to AP Style guidelines, ethnic slurs should only be used when they are “essential to the story.” By including it both in the story and its cover, we hope to depict senior Rebecca Cheng’s art and message as she intended to convey it. For more information, refer to our letter from the editors.

Lips pursed, traditional qipao dress on and fingers clenched, a Chinese woman stands rigidly in front of an American flag, demanding the attention of anyone who passes. While her figure is riveting, a quick glance down reveals the painting’s main component — tendrils of eerily-twisted red yarn linking the woman’s tense fingers to two additional canvases. One simply reads “sinophobia” — a word used to describe anti-Chinese sentiment — while the other bears stereotypes about people of Asian descent — the most alarming being the slur “ch-nk,” etched and angry across the bottom of the painting.

This haunting self-portrait is the work of Palo Alto High School senior Rebecca Cheng, who, alongside other AP Studio Art students, had the opportunity to display a piece of her work in the district office.

According to Cheng, she painted “The Puppet Master,” one of her most prized and delicate creations, intending to make a statement about the general acts of racism she and other Asian-Americans face daily. She knew the piece was provoking, but she never anticipated that the Palo Alto Unified School District would remove her work for potentially offensive content.

“It was taken down because they [the district] felt like it was not a safe place for everybody to look at that work,” says Paly art teacher Kate McKenzie. “It was so bold in its statement that they were afraid that it would really offend some people.”

At first, McKenzie says, she was told by district art coordinator Li Ezzell that Cheng she would need to provide an accompanying artist’s statement and declare the message behind her vivid piece. But when McKenzie returned to post the note, she found that the wall had already been stripped of Cheng’s painting.

Ezzell, who was tasked with deciding the painting’s future in the district office, personally took the work of art off of the wall. According to Ezzell, his ultimate decision to remove the painting was not a simple one.

“I second-guessed myself,” Ezzell says. “At first I said it is good, we’ll put up a statement, and then the next day, I was thinking [that] it would be bad if this blew up [and] reflected badly on the district art department. I ended up self-censoring even though normally I would not do that.”

Though Cheng initially created “The Puppet Master” to spread awareness about racism against Asian Americans, she was forced to take a stance on a different issue in our community — student censorship.

“The district office censored this painting by taking it down without notification,” Cheng wrote soon after the incident on her Instagram story. “This is a self-portrait that is supposed to speak to both personal experience and societal issues. It is supposed to be jarring and blunt.”

According to the PAUSD website, one of the district’s policies is to create “an orderly, caring, and nurturing educational and social environment in which all students can feel safe and take pride in their school and their achievements.” But Cheng points out that this philosophy seems to contradict her own experience.

“Not only do I feel disrespected, but I feel like my voice is being purposefully muted,” Cheng says. “I am disappointed.”

Insensitive inspirations

Cheng’s censored piece not only reflects hours upon hours of painting but also highlights a solemn issue she says is often overlooked in America — one that has affected her personally.

It was in elementary school when Cheng first began to notice the hurtful comments cast her way, which she says ranged from jabs at her school lunches to insults about her East Asian features. But the most jarring incident she remembers was in middle school, when a stranger stopped her and her mother outside a market to cast insults about their eye sizes, joke about eating dogs and yell “ching chang chong” in their faces.

“It was the most someone has confronted me,” Cheng says. “It was pretty aggressive. I was really young at the time.”

As she grew older, her exposure to hurtful comments increased as she became less sensitive to the topic. In an effort to draw awareness to the severity of the issue, Cheng decided to focus her AP portfolio on the underrepresentation of Asian Americans the prevalence of racism against this community.

“People don’t think that Asian Americans experience any racism, so it was definitely something I wanted to bring to life,” Cheng says.

“People don’t think that Asian Americans experience any racism, so it was definitely something I wanted to bring to life”

— Rebecca Cheng

Double standards

From unsettling portrayals of racial strife to mental illness, controversial subjects of artistic pieces often lead to scrutiny

And while the content may be appropriate for other environments, students may face increased resistance in what they can display in a high school climate.

Similar to Cheng, junior Max Rosenblum foundw himself at the center of a censorship issue in his video production class. In his surrealist film, Rosenblum intended to use symbolic objects to represent mental health issues, but his teacher deemed the objects he selected as crossing the line of offensive content.

Rosenblum used a teddy bear to represent anxiety — when the main character eventually stands up to his anxiety, he stabs the teddy bear with a knife. Due to this scene, the video wasn’t allowed to be submitted for a grade, says Rosenblum.

“I was told that the video was too violent,” Rosenblum says. “I was also told it would reflect badly on the program and might get us shut down by them, although I was never told who ‘them’ is.”

Like Cheng, Rosenblum was never in contact with the administration, which he was told the project might portray in a negative light; thus the criteria he needed to meet for a school-appropriate piece of art was not clarified..

While Rosenblum says he understands that lines need to be drawn in school, he also points out the many double standards across different art forms.

“The way censorship works in this district is that you can basically have strippers in Paly Theater productions,” he says. “Then, you can’t even have a kitchen knife in the films. We even read books with explicit subject matter and language, and when we make films about it, it’s not okay.”

Rosenblum comprehends the concern over showing potentially violent content in school and agrees that some form of censorship in schools should exist to protect students from gruesome images and offensive language. However, he also believes censorship in the Palo Alto Unified School District is too strict.

“The school should allow things that the majority of high schoolers encounter in our day-to-day lives or is regularly seen in mainstream movies,” Rosenblum says. “I don’t see why schools should be censoring that, as we will be seeing it anyways.”

Social Censorship

While Cheng and Rosenblum experienced censorship within Paly, other students feel its impact outside of school. Junior Eve Donnelly, who describes herself as a “social media creator,” creates ASMR-style content, including videos of her drinking fake bleach, cutting up a plush toy and eating fake glass. She says she has had videos on Instagram removed and age-restricted because of their content. These limitations prevent Donnelly’s most controversial ASMR videos from reaching her approximately 30,000-person Instagram audience. Even when they are simply age restricted, her viewership is heavily impacted, as fewer people take the time to log in to watch the video, according to Donnelly.

“That decreases your [number of] viewers, which is, as a creator, disappointing,” Donnelly says. “Especially when you work really hard on something and you really like it and then it gets taken down or restricted.”

She has also been “shadowbanned,” or temporarily prohibited from posting. When this occurs, Instagram does not notify the owner, who must discover on their own what is preventing them from publishing content.

According to Donnelly, her strong views on expression have garnered criticism, with people personally contacting her to say they disagree with the content she creates. She considers her work to be ironic, but some viewers do not see the humor in her videos and take personal offense.

“As long as you are not nonconsensually harming someone else, I think literally anything goes,” Donnelly says. “Just because you can do something doesn’t mean you should do it, but I do think you should have the freedom to do it.”

Even beyond her own art, Cheng stands steadfast against censorship, regardless of the content.

“I don’t think art should be censored in any way. It’s a form of expression and for people to have their voice heard,” Cheng says. “I don’t think it’s good to be limiting that.”

Donnelly acknowledges that she has very extreme views on this subject, but she blamessociety’s changing ideals for an increase in its incidence.

“I think that as a society, we’re getting more sensitive,” Donnelly says. “I am all for [the] majority of PC [politically correct] culture. It’s just that I do think it gets taken too far sometimes and then at that point we’re just taking away people’s freedom of speech or their freedom to post art.”

Where is the line?

From jarring portrayals of racial strife to mental illness, controversial subjects of artistic pieces often lead to increased scrutiny. And while the content may be appropriate for other environments, students face increased resistance in what they can display in a high school climate.

Even beyond her own art, however, Cheng stands steadfast against censorship, regardless of the content.

“I don’t think art should be censored in any way. It’s a form of expression and for people to have their voice heard,” Cheng says. “I don’t think it’s good to be limiting that.”

Alexander Nemerov, the arts and humanities department chair at Stanford University, takes a different stance on the issue.

“If there is some oversight from an administrator or teacher, I would not necessarily call it censorship,” Nemerov stated. “I might call it dialogue, [a] conversation, in which both parties can learn as they come together to talk about the art in question.”

However, Nemerov says that if an art piece was inappropriately removed, he would advocate on the student’s behalf because student expression plays an essential role in the overall a person’s development.

“Learning how to express yourself takes a lifetime, even if we all have moments of extraordinary clarity, where we say — or paint — exactly what we feel, even when we are very young,” Nemerov says. “Student expression is important because it is part of a lifelong process.”

Jody Maxmin, an associate professor of art and art history at Stanford, also supports student expression. According to Maxmin, only art that incites hate should be censored.

“The only justification for censoring student art is when it endorses hate, bigotry, bullying and other forms of prejudice and violence,” Maxmin stated.

And although some may regard certain topics as too provocative, others believe that the right to express messages through the arts is etched into our first amendment rights.

“Student expression is all-important. You [students] are, after all, the future of the country and of the world,” Maxmin says. “Once young people alert us to the folly of our ways and dissatisfaction with the status quo, there is no limit to what we can achieve.”

Mackenzie also says that controversial art bears broader societal implications. Regardless of their respective media and varying motivations, when most artists decide to share their creations, they have one primary purpose in mind — to appeal to emotions and share a specific idea.

“Art is offensive, and it is one of the reasons that artists do work”

— Kate McKenzie

“Art is offensive, and it is one of the reasons that artists do work,” McKenzie says. “It [daring art pieces] shocks people into thinking and sometimes changing their minds.”

But art does not need to be outwardly bold to be important. It does not have to dominate the room — sometimes a message can be portrayed without being loud.

“Much of the most powerful art is subtle,” Nemerov says. “It does not seem to offend or challenge our most cherished ideas and assumptions. It rather works by slow and quiet degrees. The measure of its power is that it does not need us. Art is slow, art takes time; that is its provocation.”

Regardless of the content, art provides a form of self-expression, and a reaction from the audience is just an added benefit.

“Just go for it,” Cheng says. “Why not? If it’s something that’s close to you and is important to you, I don’t think other people’s opinions should inhibit that.”

Read more related stories