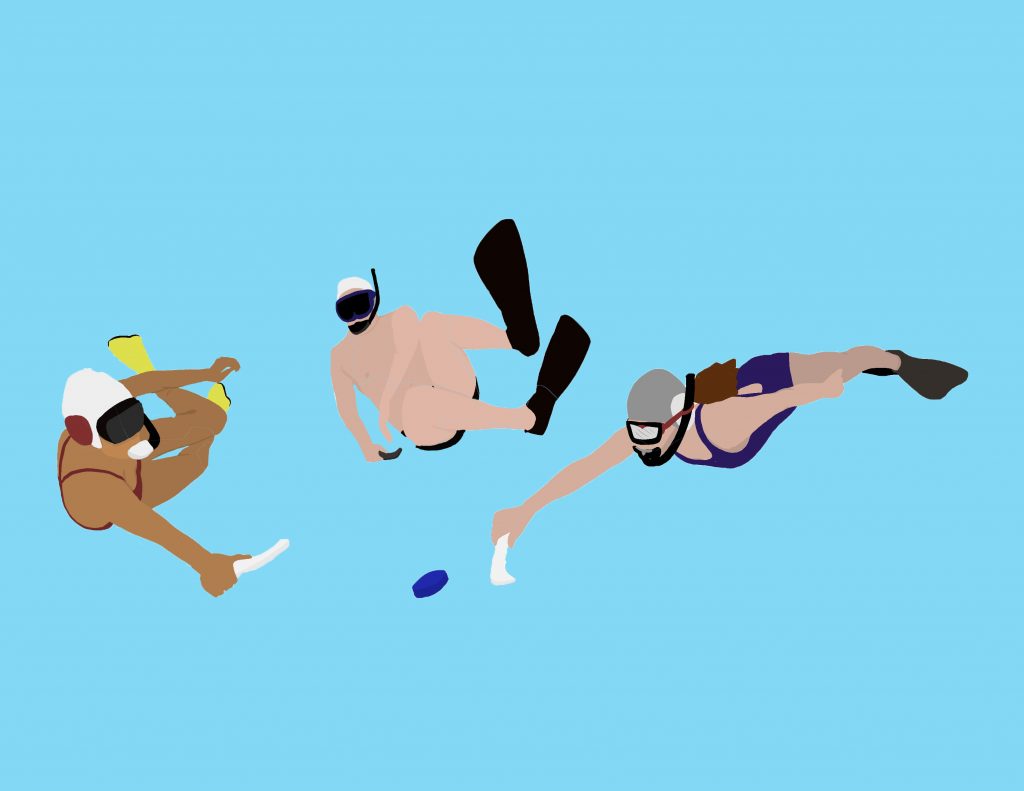

The video begins in silence as swimmers, equipped with snorkeling gear and fins, swarm around the puck at the bottom of the pool. With pusher sticks in hand, they hurry to gain control of the puck until one successful player escapes from the crowd and passes to their teammate.

Evan Mazurov, a Palo Alto High School freshman, is one of few students at Paly who play underwater hockey — the lesser-known cousin of field or ice hockey.

How it all started

Mazurov was introduced to the sport by his friends and has been playing for a little less than a year now.

“They just called me about a poster they saw at Burgess Center inviting people to join … so we signed up,” Mazurov said.

Looking back on his first game, Mazurov recounts how perplexing underwater hockey was at first.

“I felt very confused, I didn’t really do much and since I didn’t swim for a long time it was kind of difficult for me to keep up with everyone,” Mazurov said.

During his time playing, Mazurov has improved in swimming and competed against other teams. While underwater hockey may be difficult at times, Mazurov enjoys the collaborative team aspect of the sport.

Story behind the sport

Underwater hockey — also known as octopush — is a water sport that originated in the early 1950s in Great Britain as a way for scuba divers to stay in shape and stay entertained indoors during the cold winters.

To play, two teams of six compete against each other to move a puck across the bottom of a swimming pool into the opposing team’s goal.

“They just called me about a poster they saw at Burgess Center inviting people to join … so we signed up.”

— Evan Mazurov, freshman

Players wear fins and a snorkel mask, and they carry a small 11-inch pusher stick with a thick glove to push the puck at 6 to 13 feet below the surface of the water.

Each team starts at one end of the pool touching the wall with one hand, while the puck starts in the middle. Both teams race to get the puck when the buzzer goes to start the game.

Like many other sports, there are tournaments and championships that teams can compete in. Mazurov has yet to participate in a tournament but hopes to in the future.

“I want to go to a tournament but [my team and I] weren’t able to go because we didn’t get far enough,” Mazurov said.

Unfortunately, Mazurov has not been able to play any underwater hockey games since the start of the pandemic.

Prior to COVID-19, Mazurov practiced at the Menlo Swim and Sport Burgess location, one of few local teams that offer underwater hockey training.

Mazurov regularly had underwater hockey practices, which usually consisted of swimming and breathing exercises to ensure that players could remain underwater for extended amounts of time.

Now, without a pool to practice in, Mazurov has not been able to train for underwater hockey, though he keeps in mind the importance of regular exercise.

Although Mazurov is looking forward to continuing playing underwater hockey once COVID-19 restrictions are lifted, he sees it as just a hobby. For now, he waits for the pool to open so he can play again.

Related Stories

Pool principles: How swimming taught me to succeed