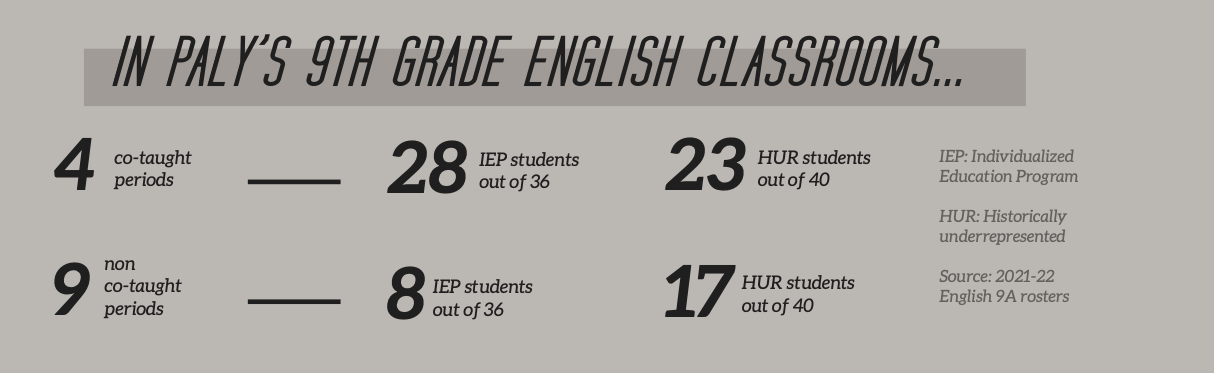

Within Palo Alto High School’s freshman English classrooms, there are four co-taught periods and nine non-co-taught periods. Out of all historically underrepresented students in the freshman class — students of Black, Latino and Pacific Islander heritage — over half are on co-taught rosters. Out of 36 students with Individualized Education Programs, 28 are on co-taught rosters.

In Paly’s co-taught English classrooms, one teacher holds a State of California credential in teaching English while the second is trained in serving students with IEPs: legal documents detailing a student’s mandatory accommodations — such as co-taught minutes — for success.

When Paly administrators place such IEP students into a limited number of English 9A and 10A periods, the result is a small number of classrooms with a higher relative concentration of IEP students while leaving the rest with little to no IEP students. This difference is something that English teacher Hunter Reardon, who teaches three of four co-taught English 9A classrooms this school year, is concerned about.

“You end up with a higher percentage of students who need more support in those sections of ninth grade English than all the other sections,” said Reardon, lamenting what he said in these classes was a reduced “diversity in the range of abilities or a range of ways of looking at and perceiving the world.”

He added: “It’s not good for the students who are in the classes who need more support. It’s not good for the students who are missing the perspectives and the experiences of other people in their classes.”

“You end up with a higher percentage of students who need more support in those sections of ninth-grade English than all the other sections.”

— Hunter Reardon, English teacher

For English instructional leader Shirley Tokheim, the high concentration of students with IEPs in certain English periods and not others seems like a sign of the department’s past segregation problem resurfacing. A decade ago, the English Department effectively eliminated ability-based laning by merging the previously separate English 9 and 9A lanes into the single English 9A course for all freshmen (doing the same with its respective 10th grade English course).

Tokheim attributed this decision to a noticeable lack of diversity; there was a disproportionate number of students of color in lower lanes, she said. However, this year, she has noticed that out of 40 historically underrepresented students enrolled in English 9A, 23 are in just four co-taught periods, while 17 are in the remaining nine periods.

“Our department is basically reverting back to the laning that we worked so hard to get rid of, because it tends to segregate by race and class,” Tokheim said.

IEPs in the Palo Alto Unified School District skew toward students of color. Black and Latino students consisted of the highest percentage of students with classified learning disabilities as of May 2021.

“The reality is that in this district, it is more likely that a student who is not white or Asian is going to have an IEP,” Reardon said. “It’s not a 100% correlation, but it’s just a tendency. … The result then is in co-taught classes if we have too many students with IEPs crowded into classes, then you start getting into segregation: more students of color being put together in lower lanes or ‘de-facto’ lower lanes.”

“Our department is basically reverting back to the laning that we worked so hard to get rid of.”

— Shirley Tokheim, instructional leader

Many teachers, however, believe that the co-teaching strategy delivers on its intent to provide more one-on-one support for students who need it and lightens the load that a single teacher without special education credits can handle.

“I will say the co-teacher that I had for Film [Film Composition and Literature] for a semester … was the best experience I’ve ever had working with a colleague,” English teacher Alanna Williamson said. “She was hugely, hugely helpful for the students in my class who needed more one-on-one support during work time, and I can’t get around to everyone … so she was helping me manage the accommodations.”

Positive sentiments about co-teaching exist beyond the English Department. Ten of 32 co-taught classrooms this school year are across history and social science courses.

“I have generally enjoyed co-teaching classes,” history teacher Daniel Shelton said. “Regardless of how difficult it may be at times, having another teacher in the room to divide up the kids, keep them on task and be able to reach different students is super valuable.”

History teacher Justin Cronin emphasized how co-teaching might affect “classroom equilibrium.”

“Classrooms tend to have a certain equilibrium to them,” Cronin said. “Multiple perspectives make a classroom stronger and that should be embraced. However, if the classroom equilibrium is off, a teacher may struggle to meet the needs of each student in the classroom, and could find that this particular class is not moving at the same pace as their others. Regardless of the situation, students have an opportunity to learn, whether that is content knowledge, classroom skills or simply being patient in dealing with their peers.”

Tokheim also echoed sentiments that the intention behind the co-teaching classroom setup was positive but that her longtime advocacy for alternative solutions stems from what she says is an awareness of unintended consequences.

“I have been talking about this issue for several years,” Tokheim said. “It’s been a top priority for me, but not necessary for our changing administrators. … I have reached out for at least the past couple of years to the district office to sound the alarm that this was happening — no response. And, I brought it up in my district meetings; I brought it up everywhere I can that this is an issue. No response.”

“Classrooms tend to have a certain equilibrium to them. Multiple perspectives make a classroom stronger and that should be embraced.”

— Justin Cronin, history teacher

The History/Social Science Department has a similar internal focus on the subject of co-teaching.

“There’s always been a constant conversation in the History/Social Science Department,” history teacher Jaclyn Edwards said. “But I am unaware of anything that the district is currently proposing in regards to it [co-teaching] other than the consistent message that this is a top priority. I don’t know if we see eye to eye with that messaging that they treat this subject as a top priority.”

Assistant Principal Michelle Steingart told Verde in an email that the administration is aware of what critics have called “de-facto laning,” but did not share specific information on any course of action being taken.

“In collaboration with others, we are actively working on a plan to better ensure that this ‘de-facto’ laning does not continue in the future,” Steingart said.

For Reardon and Tokheim, one possible solution would be to make the act of writing co-taught mandates into IEPs “much more conservatively implemented,” somehow removing the legal requirements from IEPs that limit Paly’s flexibility in organizing its classes at the site level.

“I just wish everyone on campus knew exactly what was going on in co-taught classes,” Reardon said. “Maybe even students who are not needing more support could become more empathetic for the students who do. … If we could facilitate a culture more like that in the co-taught classes and across campus, that would be amazing.”