Before last summer, Palo Alto High School junior Emma Wagstaff had never considered going into the field of technology or becoming a software engineer. Now, a few months later, she already has an internship with IDEO, a Palo Alto based company which designs and develops apps for children. Her life was changed last summer when she, along with 19 other girls, spent seven weeks at an intensive programming course on Facebook’s campus through a non-profit called Girls Who Code.

“Growing up, girls aren’t told that they can do whatever they want,” Wagstaff says. “That’s something they need to hear, because if you don’t believe it yourself, other people won’t either.”

Reshma Saujani, the founder and CEO of Girls Who Code, established the organization in 2012 to raise young women’s interest in technology.

“As the tech industry grows faster and faster, I couldn’t stand watching women on the sidelines of innovation — we should be leading the movement,” Saujani says. “We’re building the movement to inspire, educate and equip girls with the computing skills [for] 21st century opportunities. Our ultimate goal is to achieve gender parity in [technology].”

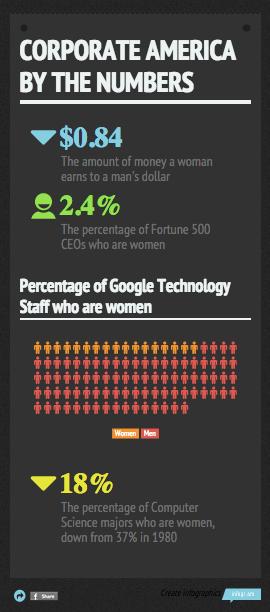

Right now, companies are not close to that parity. Although women comprise 46.9 percent of the labor force, only 16 percent of board members and 2.4 percent of the CEOs of Fortune 500 companies are women, according to a 2012 study by Catalyst Research Center. This disparity between men and women is particularly noticeable in recent diversity statistics from tech companies like Google, which reported in May 2014 that 70 percent of its whole staff are men and only 17 percent of its staff members who work directly with technology are women. On Oct. 9, Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella publicly stated that women should not ask their bosses for raises and should instead simply rely on good karma for promotion. Although he later retracted and apologized for his statement, it still sparked controversy.

Though several companies have launched programs to close the gender gap, such as Girls Who Code and Google’s Made With Code initiative, a website that seeks to expose younger girls to coding and female role models in the technology area, the troubling disparity between the genders, particularly at the high management level, still remains.

The Workforce Dilemma

According to an April 2014 study by Pew Research Center, women make significantly less than men — around 84 cents for every dollar that a man working a similar job makes, a gap that narrows to 93 cents for every dollar if the woman is unmarried.

“There’s a  huge disparity in salaries between the women and men, and it’s all very subtle,” says Nan Andrews, the director of the sexual harassment office at Stanford University. “Any gender discrimination [is] very rarely overt.”

huge disparity in salaries between the women and men, and it’s all very subtle,” says Nan Andrews, the director of the sexual harassment office at Stanford University. “Any gender discrimination [is] very rarely overt.”

The lack of women in high ranking positions may cause part of this salary gap. An April 2014 study by Harvard University found that high paying jobs are also more likely to pay women less money than men.

Sometimes women feel that their bosses do not give them responsibilities equal to those of their male counterparts with similar resumés. Jillian McNerney, robotics team manager at SRI International, experienced this sort of discrimination after she left the U.S. military, where she managed 160 people through a deployment in Iraq. Upon entering the corporate world, she noticed that she had more management experience than her peers, but was not given higher level jobs.

“I felt like the role I was put into, the position I was given and the salary I was given, in hindsight, was a lower responsibility and lower salary than I should have received,” McNerney says. “Maybe there was or wasn’t a gender bias thing, but I always wondered if I were a male, with the same kind of background, if I would have been given more responsibility and thought of as able to take on more management responsibility.”

However, male dominance in companies is not the only reason for pay inequity. Andrews believes that women in corporate America also bear responsibility for the existence of any gender gap.

“Women do it [discriminate based on gender] too, it’s just we don’t understand how we’ve been acculturated to think this way,” Andrews says. “When the salary disparities happen, when the opportunities are not given, it’s not something that people are willfully doing.”

These ingrained biases against women in high-powered jobs are often hard to prove. Rarely do two people have the same level of education, the same level of experience, and do exactly the same amount of work. This makes exactly identical jobs hard to find, and thus it is hard to prove that women make less than men for doing the same amount of work. Data cannot explain whether women are paid less on an individual basis or simply not given much representation in the higher-paying positions, but overall, women do make less money than men.

“The lack of transparency of wages and flexibility in schedules and bias in leadership and perception all contribute to the gap,” junior William Zhou says. “In general, I don’t think that there’s one biggest issue that women face in corporate America, but instead a group of issues that create the inequality that we see in today.”

Map of Companies and Programs Addressing the Gender Gap

Accomplishments

Although gender disparity remains an issue in the American workforce today, the government and individual companies have taken many steps toward eliminating the salary gap. Not all of these steps are new and revolutionary; in 1963, the U.S. Congress passed the Equal Pay Act, which states that employers cannot use gender as a reason for giving two different people different wages. In 2009, Lilly Ledbetter, a former employee at Goodyear Tire and Rubber Co., filed a case against the company after she discovered that she was paid significantly less than her male peers but was denied a hearing by the Supreme Court on the basis that she would have had to file her claim within 180 days of her first paycheck. Congress swiftly passed the Lilly Ledbetter Fair Pay Act to rectify the issue, allowing women to file a pay discrimination suit long past the initial act of discrimination.

The National Women’s Law Center reports that although the U.S. has still not achieved complete parity with regards to gendered salaries, the 84 cents a woman gets today for doing the same job that pays a man a dollar would have garnered her closer to 60 cents in the ’60s. In addition to salary increases, more companies have become aware that they hire less women than men and are working to rectify it.

“From the company perspective … if you’re in a management position and you have objectives to meet … how do you hire at a certain rate and force a distribution of gender [or] ethnicity?” says Jaime Tenedorio, the vice president of engineering at Scanadu, a biomedical engineering startup company. “It’s really hard. To be fair, there are companies that do bend over backwards to try and do that.”

One company that has tried to increase the diversity in its hiring is Google. In 2013, Google had half of its employees take workshops to learn about any unconscious biases they have that mig ht be impacting their hiring decisions.

ht be impacting their hiring decisions.

Another aspect that companies have improved upon is flexibility in allowing all working adults to balance their home and work lives. Women have traditionally been responsible for keeping the home and raising the family, which makes it hard for them to balance working high-profile, full time jobs.

“I’ve seen a lot of companies in Silicon Valley take an approach to really make sure that family is first and that man or woman, you feel like you have the resources and time needed to focus on family,” McNerney says. “It creates an environment where you feel very comfortable asking for time off and you feel comfortable asking for personal or family issues without feeling like there’s repercussions [to your career].”

For example, companies like Google and Yahoo have begun offering both maternity and paternity leave, as opposed to just maternity leave. This means that the both parents are now also able to focus on their family, allowing the mother to spend more time at her job than before.

The Next Steps

Since the passage of the Equal Pay Act and the creation of many programs to eradicate the gender gap, much progress has been made, but the salary gap persists and women are still less likely to be hired for high level positions than men. Although the Lilly Ledbetter Act represented a large step toward gender equality, Congress has not passed many other bills which would help women in the workforce, nor has it signed the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) Treaty. This treaty, adopted by the U.N. in 1979, seeks to end discrimination against women on an international level.

“187 nations have ratified CEDAW, and the U.S. is one of only seven that has not,” says Glennia Campbell, a lawyer and political activist. “If companies are serious about ending gender discrimination, they would stop supporting people in Congress who oppose the Equal Pay Act and CEDAW.”

Another important concern to gender equality advocates is the lack of women in technology, as it is a relatively young industry.

“1.4 million jobs are going to be open in the tech fields by 2020, but at current rates, just three percent of them will be filled by women,” Saujani says.

In fact, between the 1980s and 2012, the percent of female computer science majors actually decreased from 37 percent to 18 perc ent, according to the National Center for Women & Information Technology. While less women major and choose to work in such fields, there are still candidates who are qualified for the job but not getting hired, Andrews explains. Additionally, women suffer from a lack of support in an environment that caters solely to male colleagues.

ent, according to the National Center for Women & Information Technology. While less women major and choose to work in such fields, there are still candidates who are qualified for the job but not getting hired, Andrews explains. Additionally, women suffer from a lack of support in an environment that caters solely to male colleagues.

“It is an advantage for a woman if she can be fearless and substantive in her chosen area, but sometimes the environment is not completely hospitable to that,” says Diane Greene, a cofounder of VMWare and board member of Google, Intuit and MIT. “When it is not, both men and women can help by identifying and surfacing the specific issues. I’d like to see some focus on identifying rewards that are skewed towards being meaningful to the majority of women.”

According to Andrews, this environment must be established by a whole company effort.

“It has to come from the top down,” Andrews says. “It has to come from the president or the CEO. Employees [need to] keep getting messages, from the top, about diversity in the workplace and how they value more women [in their company].”

Because there are less women who do manage to reach high level positions, competition may form between women who are fighting to break through the invisible “glass ceiling” above them that prevents them from achieving the same success men do. If women believe that there is only one spot for a woman in high-level positions in their company, they may try to damage the other woman’s chances in order to increase their own.

“One important thing is getting support from your own sex as well,” says junior Minyoung Kim, the co-president of Paly’s Entrepreneur Club. “They [women] also have [to face] competition between women, so when there are women in higher positions, there will be other women who are jealous.”

In addition, companies and schools can encourage and enable women to pursue careers in technology and management. By the time they graduate college, there are already more men than women who have majored in computer science and are available to work in technology.

“We need to get more younger women interested in these issues so they will start in the pipeline early,” Andrews says. “You don’t start in college; that’s too late.”

The lack of women in the technology industry can originate as early as primary school if girls do not view math and science as subjects they can succeed at.

“Girls are more likely to say, ‘Oh, I can’t do math,’ or ‘I’m not good at [it],’” says Paly grad Ayelet Bitton, a software engineer at Quora. “Everytime I hear a girl say that, it just breaks my heart, because it’s just not true … Providing opportunities for girls who are in middle school and high school, younger and older, is really important.”

Women may also be intimidated by a future of working around gender discrimination and stereotypes, and may choose to go into other, lower paying fields where they will not be treated as minorities, inadvertently contributing to the gender gap in corporate America.

“In the technology area, I think it starts actually not only in college but in high school,” Tenedorio says. “Girls are … socialized to not be as good at [or] think they’re [not] as good at math and science. I think that … [women] are way underrepresented [in] the portion of the applicant pool to college that is female.”

Female role models in the corporate world may inspire young women to also pursue their own paths to career success. If young women are not presented with role models in the corporate world, they may not know of their own corporate potential and be discouraged from certain fields.

“I grew up in a family full of female engineers, so I was never under the impression that only men were engineers,” Bitton says.

McNerney says that veteran women in corporate America can come forward to influence young women to believe that life in the workforce can be better than they may perceive it to be.

“It [life in the workforce] is fightable; it’s fun; it’s amazing,” McNerney says. “I think we as older generations need to break those perceptions by acting on the things that we say are important. If gender equality in the workforce is important, we should be practicing that and taking steps towards closing that gap.”