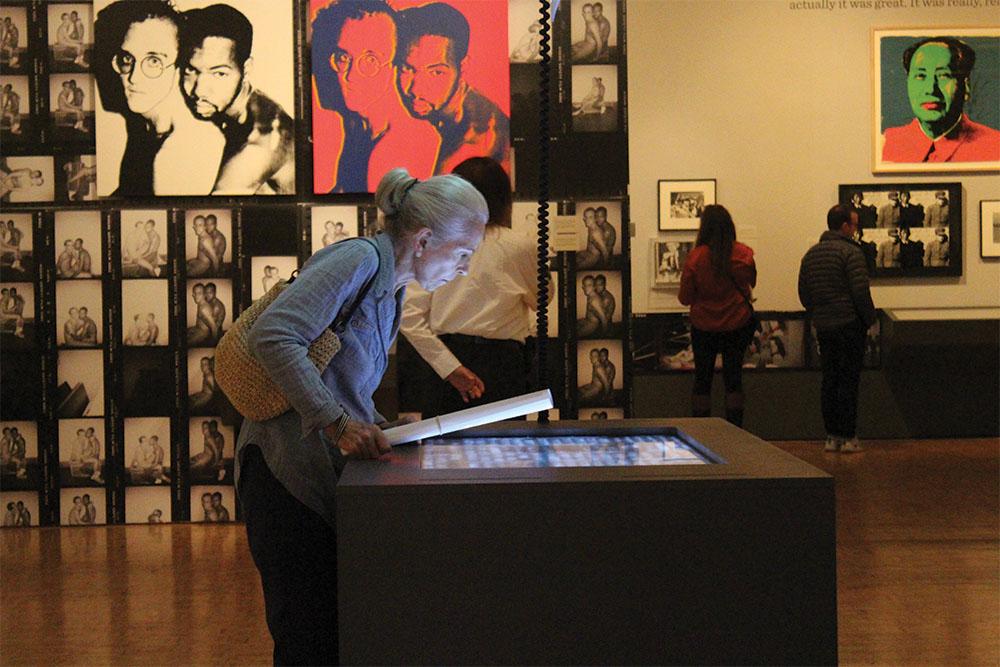

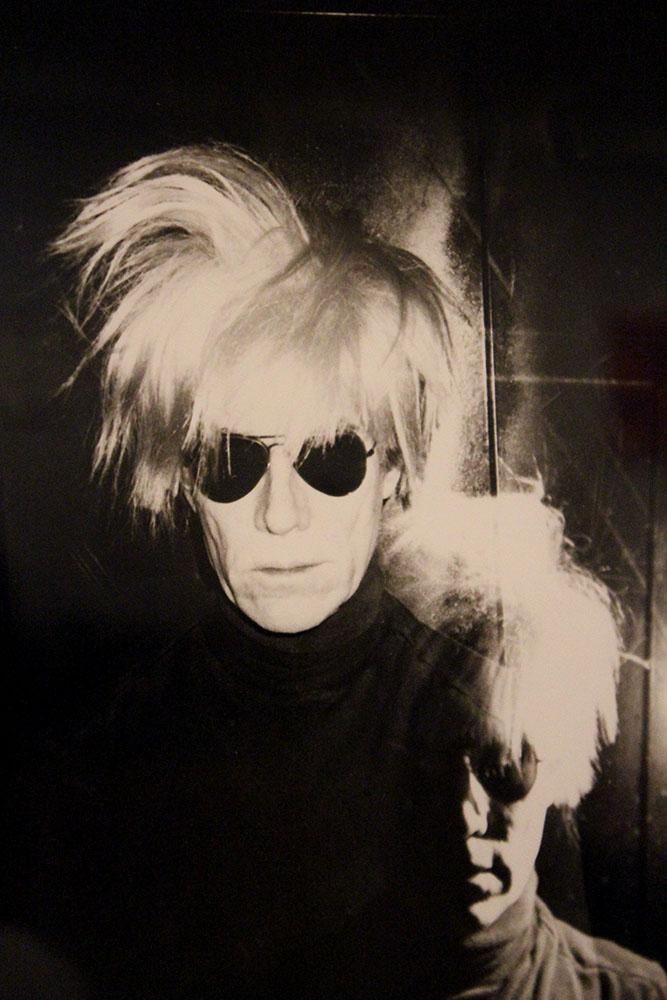

At first glance, the new exhibit at the Cantor Arts Center is anything but Andy Warhol. Bare of the renowned pop artist’s classics like “Campbell’s Soup Cans,” the Cantor Arts Center’s ongoing exhibit “Contact Warhol: Photography Without End” presents the vivid, intimate and sometimes sloppy behind-the-scenes moments of Warhol’s creative process.

The countless photographs on display in the Cantor are only a small selection of the impressive 130,000 photographic exposures gifted to the Cantor in 2014 by the Andy Warhol Foundation.

Unlike other exhibits featuring Warhol’s art, such as those in the Museum of Modern Art in San Francisco or the Getty Center in Los Angeles, this exhibit reveals a new side of Warhol with work never meant to be seen by the public eye, let alone as art.

The artificial fascination

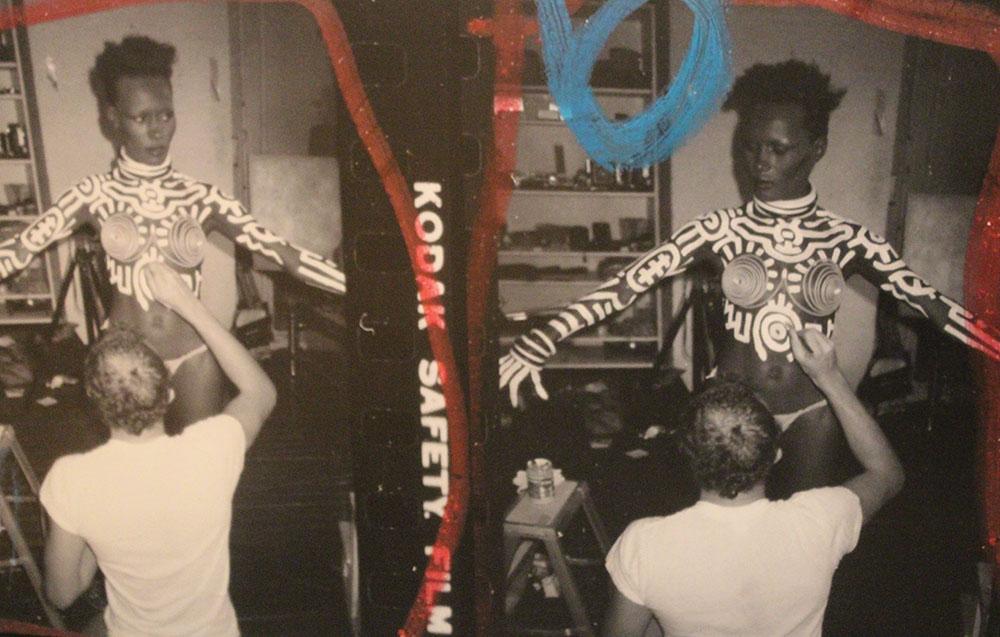

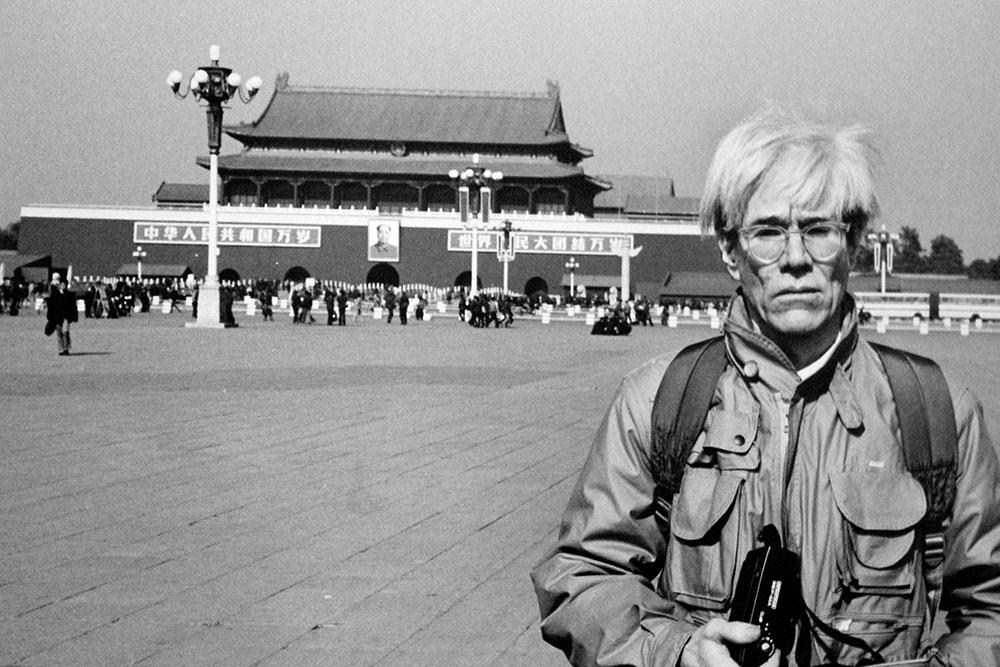

Although Warhol is best known for his brightly illustrated and sometimes controversial pieces, known as “pop art,” much of his inspiration originated with photography. Warhol documented all aspects of his life, including parties with celebrities.

Because the photos in this exhibition were never meant to be published, viewers can glean a more complete understanding of Warhol’s artistic process.

“A lot of times I think the contact sheets are described as ‘the closest you’ll get to Warhol’s diary,’” says Stanford University student Lexi Bard Johnson, who researched the curation of the exhibition.

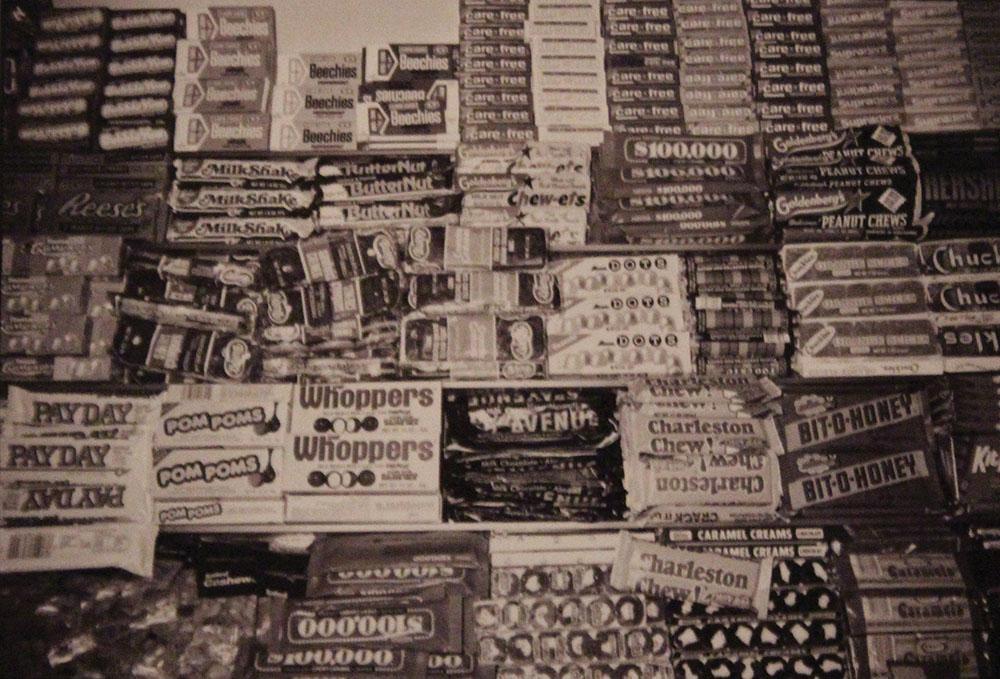

According to Johnson, the contact sheets — negatives from a roll of film — highlight Warhol’s obsession with excess in daily life. Some contain photos of rows upon rows of clothing, grocery aisles and flea market items.

“Everything is there and nothing is there, which I think is totally consistent with Warhol”

— Lexi Bard Johnson, Stanford University student

Despite this, there are still many parts of his life that were almost never photographed, such as his own apartment in New York.

“He takes an entire roll when they go to Aspen, of two parked cars in a parking lot,” Johnson says. “So, there’s kind of like, everything is in there and nothing is in there, which I think is totally consistent with Warhol.”

“Gay gay gay”

As Warhol says, “everything is gay gay gay.” The contact sheets show much more of Warhol’s participation in gay culture throughout his life than his art, such as attending Fire Island, a “queer enclave” near New York, and pictures of himself with his boyfriend.

As a closeted gay man throughout much of his life, Warhol focused mainly on creating advertisements and less controversial forms of art, such as paid portraits of celebrities, when his career first began in the 1950s.

Yet, as American culture became more accepting of the gay community in the 70s and 80s, so did Warhol’s comfort surrounding his identity. The exhibit focuses on Warhol’s final years, featuring images of gay celebrities, drag queens and even some shots of himself in drag. However, his involvement with the gay community dwindled after the AIDS epidemic of the decade, halting his association, and thus photographic content, with gay celebrity figures.

“None of these [pieces] can be separated from one another and that to me is what makes them queer.”

— Richard Meyer, Stanford University professor

These polaroids allow the viewer to understand Warhol’s deviance from cultural norms, not only due to his portrayal of homosexuality but also through his expression of gender and his documentation of these private aspects of his life.

“None of these can be separated from one another and that to me is what makes them queer,” says Richard Meyer, one of two curators of the exhibition and a professor at Stanford University.

Figment

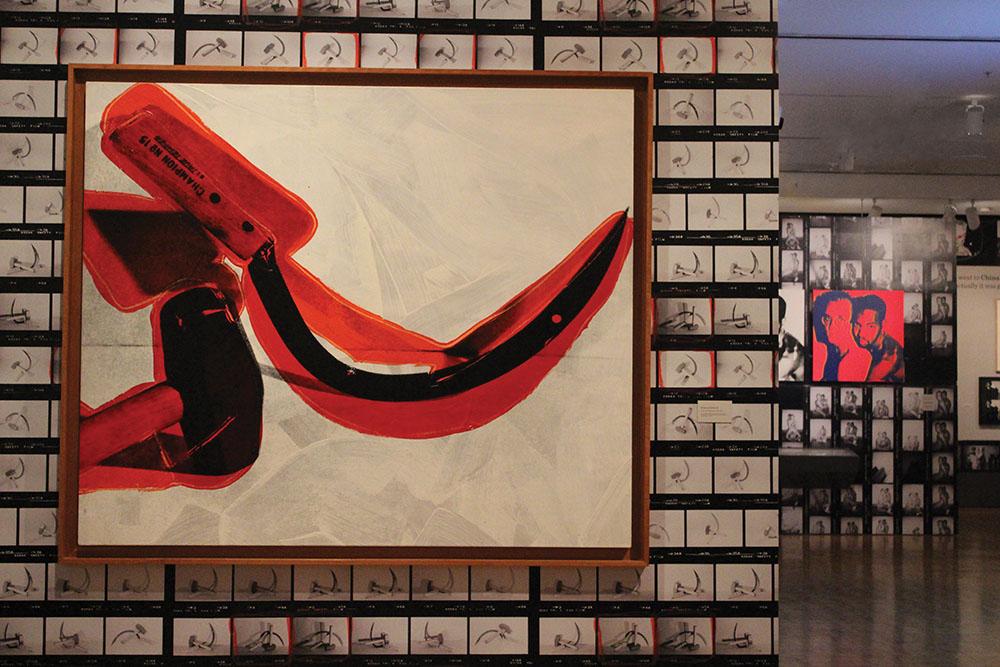

Although Warhol only wanted his tombstone to say “figment,” he has had a much bigger impact on the world. With over 130,000 images to choose from, curators had difficulty selecting which ones to showcase. Ultimately, they also incorporated many of Warhol’s other works, such as silkscreens, polaroids and negatives to create a cohesive, informative exhibition with bright pops of color that are appealing to the eye.

“I think those kinds of moments are probably my favorite in the show,” Johnson says. “Where you see multiple media with which Warhol was working simultaneously put together.”

In addition to the exhibition, all 3,600 contact sheets have been uploaded to the Cantor Arts Center’s website, launching these photos from obscurity to sudden accessibility by anyone.

Despite Warhol’s reluctance to show his photos during his lifetime, this exhibition can provide a unique look into Warhol’s artistic process, Warhol’s personality and the experience of queer people in the ‘70s and ‘80s.

“It would be remiss to say there is only one takeaway,” Johnson says. “I would hope that everyone has their own takeaway and things to think about, and are drawn to different elements or aspects of the show.”