Sophomores Alyssa Sievert and Kimberly Martinez sit huddled together like penguins, wrapped in thick jackets with their lunch bags and dishes scattered in front of them. The Palo Alto High School students sit on the same side of the table, alternating between chatting and chewing, and talking animatedly between bites.

Sievert believes Paly has a culture of trust, often seeing groups of students who can share secrets with each other, care about each other and, most importantly, trust each other. The biggest indicator of trust, Martinez says, is her ability to confide in Sievert.

“We [Sievert and Martinez] tell each other that ‘you can trust me if you need someone to talk to, or a person to hold your secrets,’” she says.

Trust, sometimes earned, sometimes given, can be easily noticed between these two friends. It is their seemingly shatterproof trust which makes them ideal representatives of Paly’s culture of trust.

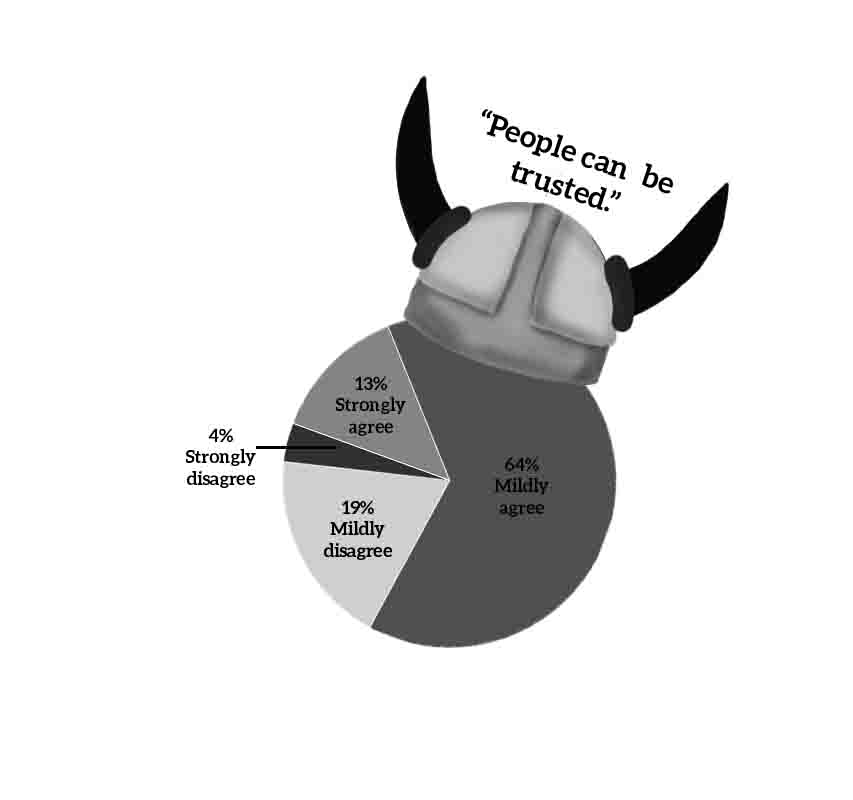

An informal survey of 164 students conducted by Verde earlier this month from 11 Paly English classes, found 77 percent of students agree that people can be trusted, and 57 percent of students say that Paly culture breeds trust.

While we did not survey the entire population, student interviews in combination with survey results demonstrate what Paly students think of trust.

Martinez and Sievert appear to have their trust set in stone, but the general tendency to trust varies along axes of grade, sexuality and race.

Christopher Farina, an AP Psychology teacher at Paly, states in an email that while he is not sure about the specific research, there are a few factors which go into our ability to trust.

“We tend to trust people, one, who are similar to us, two, who exhibit some kind of prosocial behavior towards us which we can then reciprocate, and three, people that we spend more time around.”

Student, however, all have different ideas about what makes or breaks trust and what we can do to foster a trusting environment moving forward.

Not so black and whit

For students of all different races and ethnicities, over half agree that Paly students can be trusted. However

while most students are able to trust their peers, the percentages vary between racial groups.

White students are the most trusting of all racial groups. Seventy-two percent of white students report that they could trust other Paly students. Asian American students have the second highest rate of trust, with 66 percent saying that Paly students could be trusted.

Historically underrepresented minority students (Latino, African American and Pacific Islanders) had lower levels of trust, with 63 percent of students reporting that they can trust other students.

Sione Latu, a Polynesian American senior, says that while he doesn’t know the reason for it, he generally

sees people of the same race sticking together.

“When we talk about trust, we only stay around our certain groups and we don’t explore outside of our race,” he says. “I’m not sure why, but I think we tend to trust our friends only and the peers that we hang out with, but not between ethnicities.”

Latino senior Aizzak Cerrillo-Barajas has a different perspective. He says that similar backgrounds and upbringings, rather than ethnicities themselves, are what bring students together and encourage them to trust more.

“I feel like between races it comes down to the fact where it’s based on background,” Cerrillo-Barajas says. “I trust people who have [a] similar

situation to me.”

“I feel like between races it comes down to the fact where it’s based on background. I trust people who have [a] similar situation to me.”

— Latino senior Aizzak Cerrillo-Barajas

Junior Allison Salinas, a Salvadoran-American student, says that mistrust stems from separation caused by the establishment of groups or cliques, especially those with people of similar ethnicities.

“Our clique is definitely closer together because we have the same culture — we’re all Spanish so we can speak Spanish together,” she says. “I think people feel intimidated, not just by our clique, but by other cliques which are especially made up of people of a certain ethnicity.”

Salinas says that Paly students need to work on bonding with each other, specifically those from different social groups. While unfamiliar students may come off as intimidating at first, Salinas says that it’s easy to become closer with others by simply talking with them.

“I think the solution is mostly about keeping an open mind,” Salinas says. “It’s mostly just a mentality that you might have.”

How do LGBT+ students trust?

Students who identified on the LGBTQ+ spectrum report an average lower level of trust, with 62 percent of LGBTQ+ students saying that they can trust other students.

Senior Maddie Lee, president of the Queer-Straight Alliance Club, says that overall, she and other local

LGBTQ+ students are able to trust at the same rates as other students due to the supportive community

have in Palo Alto. In her experience, she says, mistrust within the general LGBTQ+ community stems from a lack of understanding.

“I think that it’s not so much here about intolerance as it is about ignorance, just a lack of understanding,” she says, “As a whole people are so accepting, that people who are ever insensitive, most of the time, I find it’s just because they don’t know better.”

Lee says that for most LGBTQ+ students, it is not a problem of who to trust and who to not trust, but rather about finding someone who you can have open dialogue with.

“That’s what trust is about, is being able to have that emotional vulnerability and know that it’s not a weakness,” she says, “I think that especially with LGBT youths, being able to talk about your issues is a great deal of what it means to work through those issues.”

Junior Robert Vetter, who is also a part of the LGBTQ+ community, says that trust is developed on an individual basis and less based in groups.

“I feel like I can relate to people in the LGBT community better than I can relate to others, but I don’t think that translates into a higher level of trust,” Vetter says. “I trust people based on my personal relationship with them, not their sexual orientation.”

Gender inequality in trust

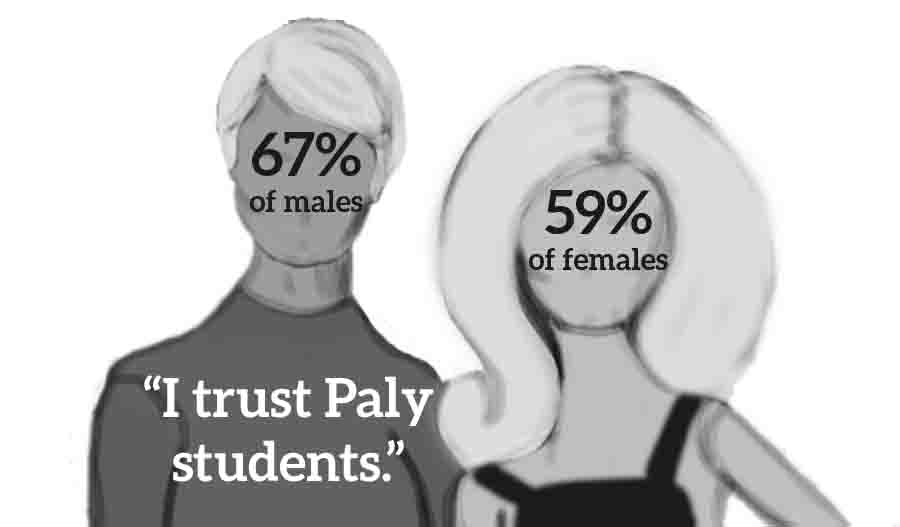

When it comes to gender, there is a discrepancy between trust and perceived trust. Sixty-seven percent of males students report having trust in other students while only 59 percent of females report trusting other students. However, when it came to perceived trust, 54 percent of students say that female students, in general, trust others more.

Before becoming president of Paly’s Intersectional Feminism Club, Arianna Seay says she went through a self-described “phase” in middle school where she would gravitate toward friendships with boys and shun friendships with girls. Yet she would only trust girls with her secrets and problems.

“I still thought girls were still more caring and thoughtful about my feelings and my opinions than guys ever were,” she says. “I was always afraid of trusting them, and how their reaction would hurt me. I was perpetuating those gender roles in my mind. I thought they’re just more harsh, and they don’t care about your feelings.”

Cerrillo-Barajas says that social norms and the pressures associated with them cause male students to trust each other less. While he feels that the social norms regarding masculinity are diminishing, many of these pressures still exist, resulting in a lower level of trust.

“With guys, especially nowadays, we can say anything and it is okay,” he says. “But it [gender norms] is still ingrained into lives and we still try not to show what we may feel.”

Trust the process

While different factors influence students’ abilities to trust, the Paly population generally reports that students are able to trust other students. Although some Paly students have certain reservations about how students trust each other, most are optimistic and have ideas about how to improve trust among students.

Sievert says that trust is ultimately dependent on one’s attitude to those around them.

“It depends on the type of person you are,” she says. “If you trust someone enough, if you deem them trustworthy enough to actually be comfortable around them, then I think you could build a really strong friendship base to the point to where you’re best friends.” v