“Romeo and Juliet.” “Macbeth.” “The Great Gatsby.” “Lord of the Flies.” “Of Mice and Men.” “The Crucible.” “Hamlet.”

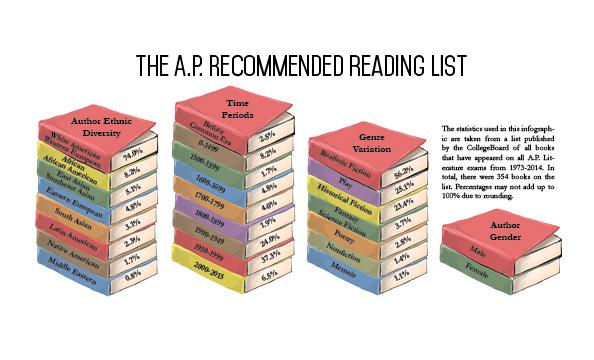

What do all these books have in common? They are “classics” — often from the 1800s or some other bygone era — written by white men, mostly in the genre of realistic fiction. And, unfortunately, they make up the majority of our high school English reading curriculum.

At Palo Alto High School, the English curriculum is generally chosen solely by the teachers and educational board, allowing little freedom for students to determine what they read. Additionally, the selections are normally made up of white male authors, depriving students of other, equally important world views such as those possessed by women or authors of different ethnicities.

Although the current curriculum seems one-sided, in the past, there have been attempts at Paly to diversify the curriculum by adding elective courses, such as Women Writers and Writers of Color, that focus on diverse authors. However, because so few people signed up for Women Writers or Writers of Color, they no longer appear in the course catalog, and teachers must find a different way to incorporate diversity into their classes. Other electives do succeed in offering students the opportunity to read different genres. Many teachers have already succeeded in diversifying the authors and content of their curriculum to be more representative, as well as giving their students more choice in their reading, but not every English teacher has adopted these practices.

Examining and analyzing different voices, genres and viewpoints is essential to our growth and development as citizens in our pluralistic society. Though the current English curriculum does not allow for this, English teachers can help solve the problem by allowing students some freedom in choosing their novels and by making the English reading curriculum more diverse.

Author Diversity

Because the current English curriculum is primarily comprised of male authors who are Western European or American, other voices tend to be overlooked. While some classes do read books like “Bless Me, Ultima” by Latino author Rudolfo Anaya and “Woman Warrior” by Maxine Hong Kingston, a woman of color, the overwhelming majority of school books are not written by these underrepresented groups. Of all the required reading books in the Palo Alto Unified School District, only “To Kill a Mockingbird,” written by Harper Lee, a white woman, is not written by a white man.

If students are only exposed to one type of book in school, they may assume the required reading is representative of all literary works. In effect, if the typical realistic fiction novel written by a white male author sometime in the 20th century does not inspire a love of reading in a student, after reading several similar books, that student may develop a general dislike of reading. However, exposure to a wider range of stories could perhaps persuade a reluctant reader to enjoy reading.

Even if students are able to read more diverse books outside of school, there is a difference between reading for fun and the type of reading students do for classroom assignments. Reading for class requires students to search for symbols, motifs and themes and analyze them effectively. By reserving this analytical treatment for books written by the same type of authors, the educational system is prioritizing those voices over that of others.

While the Western literary tradition is full of many masterpieces, so are the books of many other cultures, which include works such as “Persepolis” by Iranian author Marjane Satrapi, whose work details life surrounding the 1979 Iranian Revolution, and “One Hundred Years of Solitude” by Latino author Gabriel García Marquez. To leave those stories out of our curriculum effectively sends the message that the literary traditions of non-Western people are not important or relevant to us today.

Although Paly does not incorporate many diverse authors into the curriculums of some English classes, the recommended reading list from the California Department of Education is full of titles by authors such as African-American author Maya Angelou and Chinese-American author Malinda Lo, both of whose gender and heritage are prominent in the stories they write. By reading their books, as well as those by authors like Toni Morrison, an African-American author whose work addresses slavery and other life experiences from an African-American perspective, students will be able to grasp narratives other than those already dominant in the English curriculum given to us to consume.

Diversity in Time Periods and Genres

The lack of variation between genres and time periods also contributes to the absence of diversity in the English reading curriculum. Most of the books read for English class are in the genre of realistic fiction, and because many of these books are older, they are not necessarily as relevant or realistic as they once were. Many recently released books in the genre of realistic fiction deal with current affairs, such as “Americanah” by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, published in 2013, which covers cultural isolation. It is a shame to continually rely on the same old realistic fiction books, when new novels deal with the same issues, with the added advantage of being more relatable.

“We are still reading the books I read when I was in high school,” Paly English teacher Kindel Launer says. “There is so much out there — post-colonial, the new American stories the stories of the American Dream . . . from the 90s — are incredible.”

In addition, realistic fiction is certainly not the only genre of literature available to students for critical analysis. At Paly, some genres like comedy literature and science fiction are so rarely found in the standard English curriculum that teachers felt the need to create separate elective classes in order to give students the opportunity to read books in those genres.

“I felt like the reading material and some of the texts we were looking closely at only represented the darker side of literature,” says Lucy Filppu, who created the Comedy Literature elective. “I felt like there was a whole canon of literature we weren’t addressing, and I felt like it would bring a different side to literature.”

While electives like Comedy Literature and its science fiction counterpart Escape Literature are beneficial for Paly students, they are only available to upperclassmen, meaning that freshmen and sophomores tend to get stuck reading only one genre of literature. In addition, the scheduling system does not allow for students to take all the different English electives, so even upperclassmen cannot analyze every genre of books in class. Since it is impossible to access all of the different genres through elective classes, they should also be incorporated into general mandatory English classes.

Another genre rarely represented in any English class is young adult literature. This literature, geared specifically toward teenagers, contains many of the same literary elements as other genres more represented in the curriculum, and has the additional benefit of having high school students as protagonists, making the book more relatable and thus attractive to students. Although YA literature has a bad reputation because of occasional books with frivolous content, the majority of the genre is just as profound and more relevant to teenagers than many of the classics. Books by authors like John Green, famous for “The Fault in Our Stars,” and Sarah Dessen, who has written many prominent young adult books, are rarely analyzed in English classes.

“I think it might be interesting to read ‘The Fault in our Stars,’” Launer says. “Those are big ticket universal ideas he [Green] is talking about. How come we are not reading that? I think that that is something to think about as we move forward, thinking about engagement and thinking about how students learn.”

Student Choice

The English Department could also improve its curriculum by giving students a larger choice over which books they read in class. Recently, Launer has implemented this approach in her freshman English class by allowing her students to pick books from a bookcase full of board-approved books to study, with successful results.

“To the extent that they [students] have choice over what book they’re reading, they are more likely to prepare before class,” Launer says. “Freshmen are still highly social [and] very motivated by the need to connect. That’s a developmental piece for them, and so having the same book allows me to take advantage of the developmental phase they’re in.”

There are many potential variations to this idea of student choice, including the creation of literature circles where students divide into smaller groups and read books within those groups. Allowing students the freedom to choose their own experience while reading will likely make more students interested in learning. All of these different areas of improvement would only require small changes in the current curriculum of the English department. While there are many strong points in the way the English classes currently work, by increasing diversity of authors and genres and allowing more student choice, more students could learn to love and enjoy reading and expand their horizons.