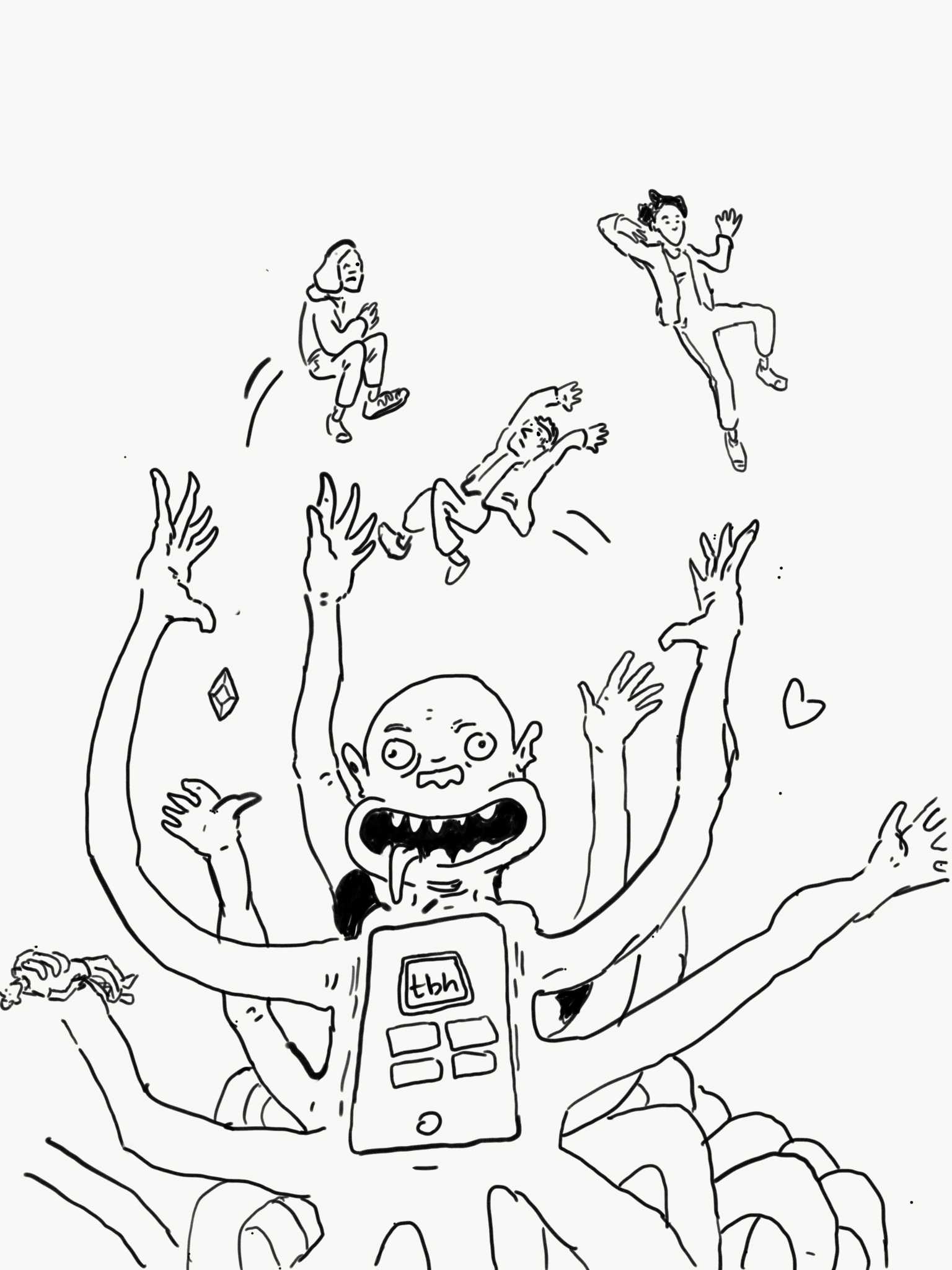

To be honest, I’m not a big fan of the app “tbh.”

While some may enjoy the short-term self-esteem-boosting effects of “tbh,” in the long term, the app only exacerbates an obsession with online validation.

“tbh” has soared to the top of Apple’s app store charts in recent months, attracting the attention of countless teens. The app, which describes itself as “the only anonymous app with positive vibes,” claims to combat issues of cyberbullying present in previously popular anonymity software such as ask.fm or Sarahah. But does “tbh” achieve what it set out to do?

The app’s positive reputation can largely be attributed to its lack of typed comments; users simply receive “positive” prompts such as “best smile,” “hotter than the sun,” or “your favorite.” The user then receives four choices — people from their friend list — that they can select as an answer for each prompt. When you are chosen for a prompt you receive a gem, but can’t see who it’s from.

At first glance, this seems like a cute and innocent idea — what’s so bad about giving and receiving compliments, without the anxiety associated with real-life interactions?

But a major issue with “tbh” stems from its element of comparison; these compliments are generated by comparing four people, prompting the user to promote one of their friends over another. This comparison issue also affects people receiving gems, since when you get a gem, you can see who you were chosen over, and how many gems your friends have received. As harmless as this idea sounds, it triggers a superficial and unhealthy competitive attitude in some users of the app.

Palo Alto High School AP Psychology teacher Chris Farina agrees.

“When you get into comparison, if they [users] can see how they rank among friends, I think that gets into some really bad issues,” Farina says. “Is the goal to get some recognition from somebody that you know? Or is your goal to end up at the top, and if so, what are you trying to do to get there?”

The larger issue with “tbh,” however, is the resulting dependence on constant validation from peers. Validation has long been an issue associated with social media outlets such as Facebook or Instagram, taking the form of likes, followers and friends. However, this issue is not as apparent on these sites because it is combined with more personal aspects, including photos and comments.

“How do we quantify what kinds of actions and behaviors get what kinds of gems? Are those really the kinds of behaviors that we want to be incentivizing in people?”

— Chris Farina, AP Psychology teacher

But in an app where the sole purpose is to vote on and receive nominations for polls, validation becomes a completely different issue, as users become fixated on earning the highest number of positive prompts, only nurturing a demand for continual online recognition from peers.

In addition, most prompts on “tbh” are extremely superficial; the app lacks the depth necessary to qualify as a source of meaningful online positivity.

“How do we quantify what kinds of actions and behaviors get what kinds of gems?” Farina says. “Are those really the kinds of behaviors that we want to be incentivizing in people?”

Some people argue that the app reduces the anxiety often associated with giving and receiving compliments in real life.

“It’s nice to get compliments from people,” sophomore Taylor Yamashita says. “Since it’s anonymous some people may be more likely to say things they wouldn’t say otherwise.”

In fact, many apps are following in the footsteps of “tbh”; for example, an app released in early November called “Sorry” allows users to accept or reject typed apologies from friends.

But is this trend really a good thing? In a world where we are constantly setting up technological barriers, these apps may do more harm than good.

Instead, we should be learning values of real-life communication and compassion; in this way, compliments can become more meaningful than a multiple choice popularity question.

“tbh” will likely fall out of favor within a couple months, but teen obsession with online anonymity will persist: an obsession that walks the line between excitement and destruction. For now, however, apps like “tbh” tend to push us into the latter camp.

As Farina says, “The absence of positive recognition can be every bit as damaging as the presence of bad responses.” v