Two days ago I scheduled my first ACT test. The website requires you to create an account and profile for yourself, then proceeds to ask what seems like an eternity of questions. These questions range from what credits you have taken, to what religion you affiliate yourself with; they can easily be answered in half a second.

But there was one question that made me hesitate: “Indicate your race. Mark all that apply.” I was stumped. As a half white, half Asian person — or a “wasian,” as we are commonly referred to — I could check two boxes. But I also could get away with only checking “white” because my last name wouldn’t betray the other half of my ethnicity. Yes, an ACT account profile is trivial in the grand scheme of college admissions, but I began to wonder what boxes I would check when I began my college applications in a year. As college application season is fast approaching, many wasian seniors will have to confront this decision.

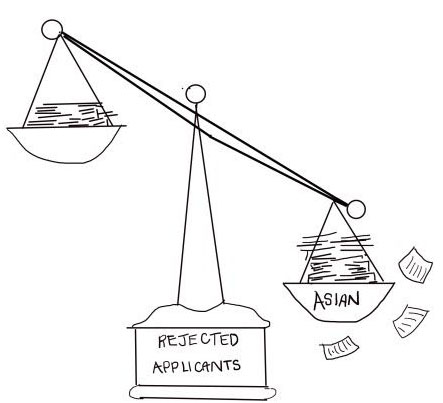

You might ask why “wasians” would possibly want to deny half of their ethnicity to a group of strangers in an admissions office. The explanation is this: Universities around the country strive to create ethnically diverse student bodies, and while the Supreme Court banned racial quotas at universities in 1978, universities can still use race as a criterion in admissions. Asian application numbers have dramatically increased at the much-sought-after Ivy League schools, while the demographic percentage of Asians at these schools has plateaued.

According to Steve Chapman of the Chicago Tribune, the percentage of Asian-American students at Harvard stayed at around 19 percent between 1992 and 2013 despite the number of college-age Asian Americans roughly doubling in the past twenty years. The bar for admitted Asian students is increasingly rising, and more and more qualified Asians applicants are being rejected. According to Thomas J. Espenshade, a Princeton sociologist, the average SAT scores for Asian students at Ivy Leagues are 140 points higher than the average SAT scores for white students.

Still, some half-white, half-Asian students are not so quick to click solely “white” and move on. Jackie Moore, a Paly alumna and freshman in college, says she was against hiding her ethnicity and checked both white and Asian in her college application. “I personally don’t think it’s worth it to cover it up; why manipulate part of my identity just to maybe, maybe, get a better shot of getting into a school?” Moore says. “In the end I just decided that it wasn’t worth it and it wouldn’t be true to who I am.”

“I personally don’t think it’s worth it to cover it up; why manipulate a part of my identity just to maybe, maybe, get a better shot of getting into a school? In the end I just decided that it wasn’t worth it and it wouldn’t be true to who I am”

– Jackie Moore, Paly Alumna

I grew up hearing my mom tell stories about her life in Vietnam and her harrowing escape to the U.S in 1975 after the Viet Cong invasion and the fall of Saigon. I take pride in having that history in my family, and in going to the temple for Tet, the Vietnamese New Year. I love coming home to the smell of pho, a traditional Vietnamese soup, and wearing ao dais, traditional Vietnamese dresses, to relatives’ weddings. Would I really want to withhold this part of me from a school? And is that school really the right fit for me if it turns me down due to my affiliation to this beautiful, unique culture?

Paly’s college counselor, Sandra Cernobori, agrees that students should not hide their ethnicity and discusses the common misconception as to why the question on the application exists in the first place.

“Colleges typically ask questions about ethnicity, race, even income because they are obligated to by the federal government if they are an institution that distributes federal money,” Cernobori says. In short, ethnicity is often not taken into account during admissions; rather, the government will not give money to universities unless they receive a compilation of data about the student demographic.

But as I walked away from my interview with Cernobori, I realized that all the questions I had asked her centered around Ivy League schools and their statistics.

In reality, many universities have an Asian population below five percent, according to their demographic reports, and if these universities are trying to build a diverse class, (most universities these days are) as a half white, half-Asian applicant interested in attending those schools, I would not hesitate to document my minority ethnicity.

So to all hopeful applicants at Paly, I leave you with this: If you truly believe race will affect your admissions to your dream college, you should do your research. What you might think is a detrimental detail in your application for one school might actually be helpful in your admissions at another school. But I urge you to remember that your own ethnicity is a beautiful part of your identity. I hope that when a university admits you, they want every single part of you. I sure hope they would want the whole me too.