With her eldest brother more than 14 years her senior, Amy Brown is the youngest of eight. The second youngest, Dana, received an exercise science degree but decided that motherhood was a more pressing concern, so she gave up her dream of becoming a doctor and now works at Hollister. Of Amy’s other six siblings, one is in jail, one owns an oil company in North Dakota, one works in education, one owns a “landscaping” service that’s really just a small-scale lawn mowing business and one is estranged. The last one, Amy has forgotten about.

Unlike her seven siblings, Amy plans on getting a masters degree in education after obtaining her bachelor’s degree from Foothill; she is on track to become the first in the family with a master’s degree.

In high school, Amy had a dose of apathy and a low GPA, which combined put her on the verge of dropping out. Yet a dental hygiene course that she took to fulfill her high school vocational credits managed to change the trajectory of her career path. The applicable job skills that she received seemed infinitely more profitable than the fruitless memorization that her other courses demanded.

She decided not to drop out of high school, and after graduating became a dental assistant at a local office. Her dream: to teach dentistry.

Now, Amy is the youngest of the 24 students enrolled in Foothill’s elite dental hygiene program, and for the first time in 57 years, Amy and her peers will be awarded a bachelor’s degree.

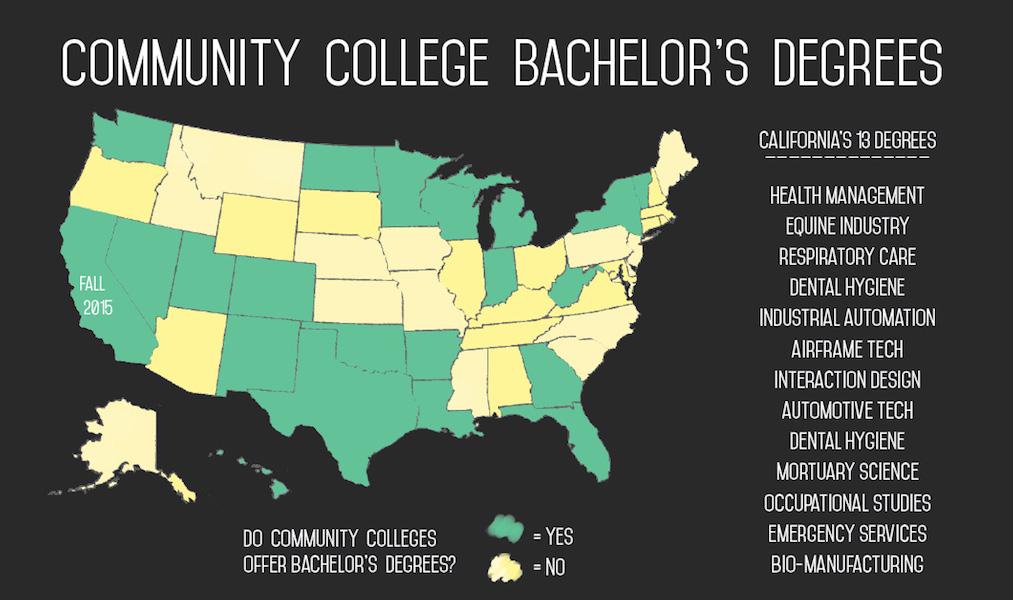

This makes Foothill’s dental hygiene program one of only 15 programs statewide that offer community college students a bachelor’s degree.

For Jessica Alban, who already completed four years of schooling at Foothill and San Jose State University, a bachelor’s degree gives her the opportunity to work in sales or marketing at Colgate instead of being confined to assisting in a dental clinic.

For Ivan Ferrer, who joined the military as a medical equipment technician straight out of high school because he didn’t want to go to college to face “real life,” a bachelor’s degree promises job security.

For Navdeep Chohan, who formerly practiced dentistry in Sweden and England but whose degree was not recognized in the United States, a bachelor’s degree gives her the certification that she needs to practice in the states.

For Amy, a bachelor’s degree makes her eligible to apply for her masters in education two years sooner than she thought, and for $30,000 less.

Closing the Income Gap

Until now, the 112 community colleges in California have only offered two-year programs with associate’s degrees, while private and public universities offer four-year programs with bachelor’s degrees.

On Jan. 1, Senate Bill 850 allowed 15 community colleges in California to award bachelor’s degrees in fields such as dental hygiene and automotive technology as part of a pilot program. This bill makes California the 22nd state to grant community college students a bachelor’s degree.

According to Market Watch, the effect of a bachelor’s degree on an employee’s life is monumental: The average worker with an associate’s degree and little experience makes an annual salary of $37,100 compared to $46,900 for someone with a bachelor’s degree, a 26 percent difference. But fast-forward ten years down the road and that gap widens to $30,000, a more than 50 percent difference.

The bill, initially signed in August, accepted applications by recommendation of each district’s chancellor last fall.

Hoping to open up new job opportunities, Phyllis Spragge, the director of Foothill’s dental hygiene program, applied to be part of the pilot program.

“We have many students that will be the first in their family to go to college or may be new to this country,” Spragge says. “Our students earn so many units while they’re in the program that they’re already at a bachelor’s degree level by the time they graduate. … When this opportunity came around, we thought, ‘This is perfect.’”

Foothill’s program is more than just a convenience; it’s revolutionary. In dental hygiene, an associate’s degrees only permits prospective employees to work as dental assistants, while a bachelor’s degree allows them to work in sales, marketing, general education or research.

“Most hygienists make around $450 a day,” Spragge says. “If you work full-time, that’s around $100,000 a year.”

According to national data reported by NBC, a six-figure salary puts these students in the top 20 percentile of Americans.

What’s more, only three private schools in California — University of the Pacific, University of Southern California and Loma Linda University — offer bachelor’s degrees for dental hygiene programs, costing students $40,000 to $70,000 per year. Universities of California and California State Universities don’t offer majors in fields like dental hygiene at all.

At $10,000 for all four years, Foothill’s dental hygiene program is 20 times cheaper, without sacrificing the quality. In 2005, Foothill’s dental hygiene program was ranked second out of the 250 programs in the nation, and in its 50 years, the program has maintained a 100 percent pass rate on the board certification exam. For this reason, Amy calls Foothill the “Stanford of dental hygiene.”

The Stanford of Dental Hygiene

On a Monday afternoon, the 24 students in Foothill’s dental hygiene program work in the training clinic in groups of three. One student lies down in the reclining chair, pretending to be the patient, while another practices her hand-eye coordination, making the maneuvers necessary to fix a simulated cavity on the first person’s tooth. The last student assesses the second one’s work and gives them a grade for their performance. Then they switch positions, and repeat.

On Tuesdays, they practice on real patients, working to improve their motor skills almost every afternoon in the clinic— by the time they graduate, they’ll have over 1000 hours of experience.

In the mornings, they go from classroom to classroom, attending lectures on subjects ranging from dental radiology to dental community health. Brenda Hanning, director of Foothill’s respiratory therapy program, attests to the difficulty of all of Foothill’s Allied Health programs.

“Students who have completed their bachelor’s at [UC] Davis or [UC] Berkeley come in and they go, ‘Oh my god, this is so hard,’” Hanning says. “It’s a different approach. When you go to school, even for a bachelor’s, you often take classes, and you focus on that class, you pass, and you forget about it —the classes aren’t linked — but our program is comprehensive. For two years, you have to build on what you learned from day one.”

When Foothill Trumps Universities

Sometimes a university education is not enough; many students who already have a bachelor’s degree attend Foothill’s dental hygiene program, as the abstract nature of their university education makes them unable to secure job opportunities.

“What happens with programs like respiratory therapy and dental hygiene is that students major in biology, pre-med or kinesiology, and then they can’t get a job, or the only job they can get pays minimum wage,” Hanning says. “They’re trying to get physical therapy jobs, but instead they find themselves working at a 24 Hour Fitness for minimum wage after completing their bachelor’s.”

On the surface, Foothill’s dentistry program provides students with a launching pad for their professional endeavors. But to the students, the program’s most redeeming quality is the bond that they develop with their classmates and professors — a sense of community that can last more than 20 years.

Unlike public universities that allow students to create a customized schedule through over 200 courses, the 24 students in Foothill’s dental hygiene program attend clinics and lectures with the same group throughout both years.

Spragge, who graduated from the program herself more than 20 years ago, is now a living testimony to Foothill’s lasting impact, still sharing a connection to many of her students who she refers to as “family.” If you ask her, she’ll list their names and occupations off the top of her head.

Like Spragge, Amy’s other professors, one of whom is editor of a well-established journal, teach not to make ends meet, but because they love the profession — rather than mindlessly reciting information from the textbook, they tell engaging stories about their experiences in the field, inspiring the students to succeed.

Finishing the Unfinished

When Spragge announced that the dental hygiene students would be receiving a bachelor’s degree, Pam Piccione, 48, broke down crying.

In 1984, as she saw her two brothers before her struggle with student loans, Piccione chose to drop out of Foothill College, believing that opting to work full-time was the “successful, mature” decision.

Last year, Piccione returned to Foothill after having children, the youngest of whom is still in elementary school. A bachelor’s degree for her means a chance to serve as a role model for her young children and finish the unfinished.

“I have wanted a degree all of these years,” Piccione says. “Now, the opportunity is knocking at my front door.”