“I don’t know why I post illegal content and talk about such explicit things. But people seem to like it,” says Allie a former Palo Alto High School student, whose name has been changed to preserve her anonymity. “I have this intense attraction towards things that are controversial, like drugs, sex, anti-religion, critiquing the government, anarchism and machiavellianism, which is why so many of my posts are political.”

Allie uses her fake Instagram account, or “finsta,” to document her feelings. From debriefing her drunken nights to talking about her health issues, she is active on her

account, posting at least once every day.

On the other hand, Allie’s main Instagram primarily features filtered photos of her surrounded by friends. The majority of the photos have been taken in exotic places, painting a different picture of her life to the majority of her followers.

The gap between posts on real Instagram accounts, “mains,” and fake Instagram accounts, “finstas,” may be one manifestation of perfectionism.

According to a study conducted by the American Psychological Association, perfectionism among youth increased by an average of 33 percent in the past 27 years, and social media could be a contributing factor.

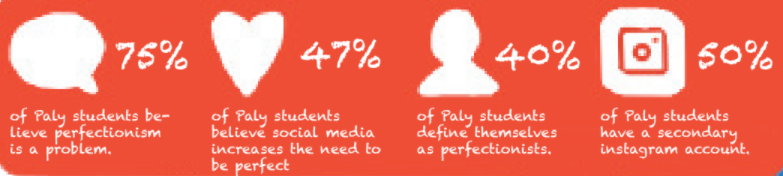

With the national increase in perfectionism, there is a corresponding rise in pressure for students to succeed. According to a Verde Magazine poll, 41 percent of Paly students describe themselves as perfectionists, and 75.8 percent believe that perfectionism is a major problem in Palo Alto.

The Instagram illusion

The rise in socially-motivated perfectionism can be attributed to the increased use of social media, stated Thomas Curran, an author of the APA study, in an email to

Verde.

“Social media offers a platform for young people to exchange curation of their perfect selves,” Curran states. “This provides fertile conditions for upward comparison — the internalization of [the] unrealistic ideal of the perfect self.”

Especially within social media, students present various versions of reality, according to junior Maddie Yen, who has three Instagram accounts.

“My private is my joke account where I’ll post things of me just screwing around, Yen says. “I only let my really close friends follow that. My third is only girls, so I do not have to filter out my private stuff.”

Main myths

Students scrutinize what they post on their “main” account, according to junior Nathan Ramrakhiani.

“Your primary Instagram could be considered like a networking tool,” Ramrakhani says. “You do not necessarily want them [people] to see all sides of you initially.”

Instagram gives teenagers a platform to share their best moments, but some students believe that this leads to a culture of obsession over their public image.

“It is a new way that young people are evaluated by their peers,” Curran says. “It [Social media] gives rise to problematic tendencies as people tie self-esteem with the amount of likes they receive.”

This externally-motivated pursuit of perfection is ingrained in society.

“It is very important in this culture to be seen as successful and appear perfect, as this is used to determine our worth and value in society,” Curran says.

Fake accounts, real stories

Private Instagram accounts are often used to share intimate or funny stories, embarrassing photos or even random thoughts.

“My finsta is for my super close friends, so I know I won’t be harshly judged for things that I post,” says sophomore Olivia Ramberg-Gomez. Students also use their finsta as a platform to share their insecurities and worries. It is perceived as a safe space to ask for advice and post opinions.

“We want to feel like we’re not alone, and that’s possible on a finsta without hav-

ing a constant conversation,” Allie says.

Finstas let people express private concerns to get the advice they need without the pressure of a one-on-one conversation.

“People are posting things about being depressed, but it gives those people a way to reach out and speak out about it rather than just containing it in,” says senior Ahmed Ali.

In this way, finstas serve as large group chats. Among students’ closest friends, they are not afraid to reveal their flaws.

“It is no surprise we put a perfect representation outward to the public but a more authentic account in private, where judgement is not perceived to occur,” Curran says.

In this way, students’ experiences and Curran’s analysis show that finstas may provide a more comfortable outlet for imperfection.

Flawed perfection

As cliché as it is, there is no such thing as “perfect,” and an unhealthy relationship with perfection can be damaging.

“If you get wrapped up in that idea [perfection], then ultimately you will get a worse result because you will be disappointed with what you have achieved — even if it is close to being perfect,” says junior Nisha McNealis.

Combating impossible expectations for oneself can be incredibly challenging, especially when those expectations are based off of unrealistic views of others.

“It’s important to remember that nobody is ever perfect,” junior Annie Tsui says. “Even near-perfect people still constantly strive to improve and are never satisfied with themselves.”