Wastebaskets are the best friends of writers and those with lofty New Year’s resolutions.

I wrote my first New Year’s resolution in fifth grade, resolving to hold better posture in class. This was during a period when I felt uncomfortable being taller than most of my classmates and slouched to appear shorter. I hoped my New Year’s resolution would make me more conscious of my back health. But inevitably, I was not successful, and to this day, I still get back pain from slouching over my desk. Although my resolutions have changed over the last five years to focus more on health and mental well-being, my commitment to them has not.

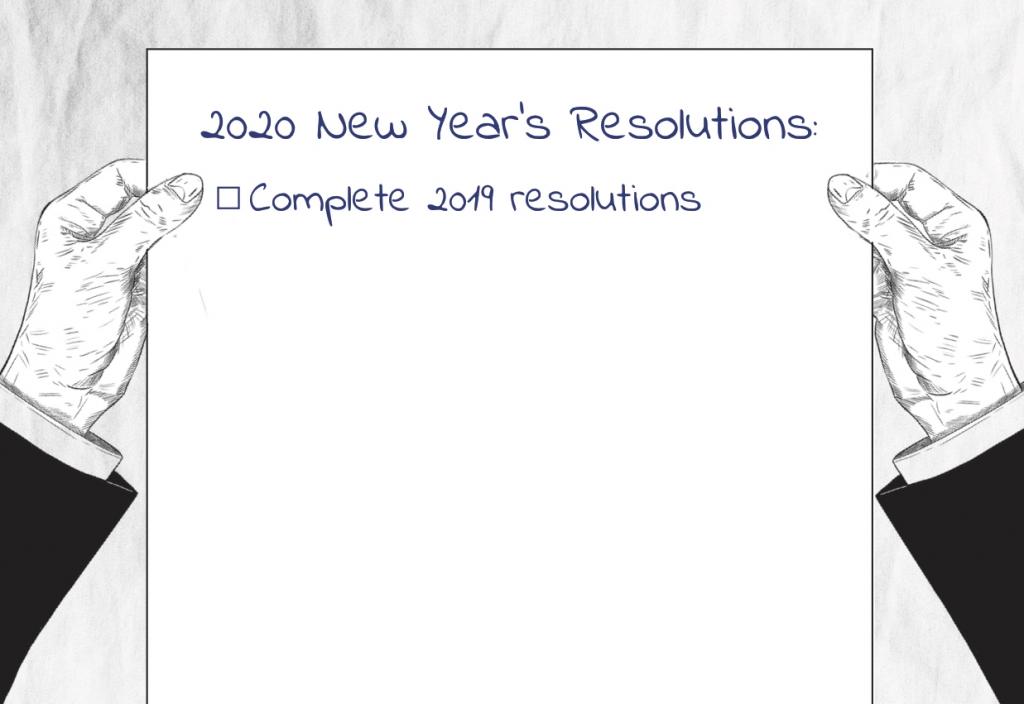

Between 2012 and 2018, I have started off every year by writing a long list of resolutions. But once the next Dec. 31 rolled around, I always end up with the same list, unable to cross any of the old resolutions off and instead adding revisions. Not only are my annual “to-do lists” a constant reminder of my inability to succeed, but my New Year’s resolutions have also turned into a vicious cycle of trying to catch up with the expectations I set the year prior.

Over the last five years, I have done extensive research; I have watched TEDxTalks explaining the “correct” process of making a New Year’s resolution and read about how to psychologically motivate myself to accomplish these goals. Yet year after year, I have continued to fail at turning my goals into realities.

Yet year after year, I have continued to fail at turning my goals into realities.

My experience with the goals and tribulations of New Year’s resolutions are quite common in the United States. According to a 2016 study published in science journal “Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin,” over 55% of New Year’s resolutions are related to health. Approximately 80% of people who make New Year’s resolutions drop them by the second week of February, according to a 2019 study conducted by Strava. A 2016 study by The University of Scranton also found that less than 25% of Americans were still committed to their New Year’s resolution after 30 days, and a mere 8% actually accomplish them.

These studies show that making New Year’s resolutions is a tradition that rarely works. In our quest to change our bad habits or continue our good practices, New Year’s resolutions are setting us up for failure.

New Year’s resolutions are designed without considering human nature. For most people, it is difficult to change a long-term habit immediately. As many New Year’s resolutions last for the entire year, these year-long goals ignore the possibility of relapsing into our typical routines; Once we fall off of our goals, the tendency is to quit until the new year rolls around again.

Because at the end of the year, many of these resolutions were only created to be later destroyed.

There is nothing special about beginning something new on Jan. 1. For 80% of Americans who plan to start a new diet, starting a significant lifestyle change on Jan. 1 is completely illogical — most of us are sleep-deprived and spend the bulk of the day sleeping in. Why should we restrict ourselves to only change once a year? It is better to take the opportunity to start over at any time.

Making New Year’s resolutions is a tradition whose structure promises failure. So as 2019 came to a close, I decided to stop making New Year’s resolutions. Because at the end of the year, many of these resolutions were only created to be later destroyed.