Living here in Palo Alto, we have the comfort of knowing that we can stay out past 7 p.m. without worrying for our life or being locked out of our home for the night. We can practice any religion we like without a threat of persecution. We don’t hear reports everyday about people being killed by our government.

The conflict in Egypt may seem a world away to us here, but it has very real effects for many Palo Alto High School students. Senior Dahlia Salem, junior Lina Awadallah and senior Mary William have all been deeply affected by events in Egy-pt.

Chaos and protests broke out in Egypt when the county experienced its second revolution in only three years. Salem, who traveled to Egypt during the summer break to visit family and friends, could not resist the opportunity to participate in the protests.

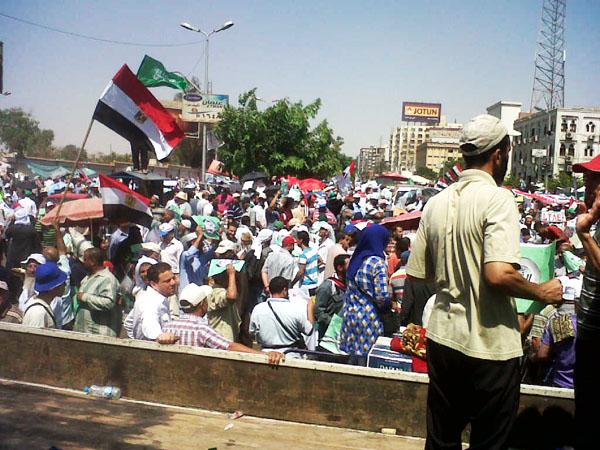

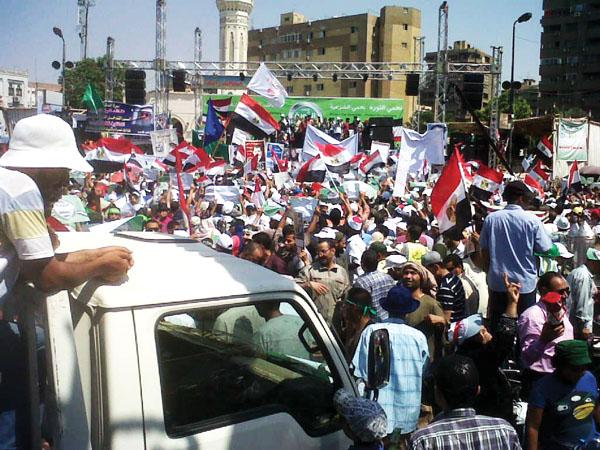

On Friday, July 26, thousands of Egyptians gathered in Tahrir Square in support of the military, responding to a call for support against terrorism by the leader of the Egyptian military. The general’s speech was in response to pressure from international governments calling his actions against the elected president, Mohamed Morsi, a coup.

“That day, instead of going to Tahrir square I went to Rabaa [the headquarters for Muslim Brotherhood supporters],” Salem says. “I just wanted to see and tell them [supporters of the Muslim Brotherhood] that what the military is doing is wrong.”

When Salem arrived at Rabaa with her father that day, she was confronted by hordes of Muslim Brotherhood supporters. The crowds were overflowing into the streets, which caught the attention of the local military patrol.

As more and more people joined in the protests, the military took action.

“Late at night, they started spraying us with tear-gas,” Salem says. “People were telling us, ‘Go inside more,’ but we didn’t want to, we wanted to get our car [and get] out of there and go home.”

Salem’s car was parked behind the makeshift barricade that the army had set up. While her father went to go get the car, she waited at a pre-arranged spot, veins pulsing with adrenaline.

“I know they were spraying in the air where I was, but I didn’t even feel it. The adrenaline, it was just, like, the terrifying situation: when you’re in it, you’re just blinded, you’re just running,” Salem says. “You don’t know what to do, you’re just so afraid. It was just tear gas, but it was just the possibility that they could shoot.”

Protesters retaliated by throwing rocks at the police. During the mayhem, Salem was hit across the brow by a rock, leaving a faint scar. Eventually, Salem’s father managed to get their car and drive to safety, just before the military opened fire.

“They fired at people, about 150 died that day,” Salem says. “It was like God’s mercy that we got out of there before the shooting started, its just, that could easily have been me.”

Although the conflict in Egypt may seem far away to us here in Palo Alto, it has very real consequences for many in our community. Salem, along with senior Mary William and junior Lina Awadallah have all been deeply affected by the events in Egypt.

Egypt has been in a state of political disorder since January 2011, when protesters swept through the Egyptian streets, calling for the resignation of dictator Hosni Mubarak. The Mubarak government tried several times to shut the protests down, but the Egyptian military took over on Feb. 11.

“I was there during the 25th of January revolution,” Salem says. “That really affected me. … It was like a string of hope. I was like, ‘Oh my God, this is it. This country’s going to change, we’re not going to be the same anymore.’”

After much turmoil and bloodshed, the Egyptian people held their first presidential elections in nearly 30 years. A new president was elected, Mohamed Morsi, of the Muslim Brotherhood, in June of 2012. There were no improvements in Egyptian living conditions after being in office for 13 months, according to Salem.

“He [Morsi] was trying to force his political views on everybody,” Awadallah says. “That’s not what they [the citizens of Egypt] wanted. They wanted to be listened to.”

Salem attests to some of the horrors that occurred during Morsi’s presidency. During a soccer match in Port Said, a city near Cairo, supporters of one of the teams attacked opponents fans with clubs, bottles and knives.

Seventy-nine people were killed during this tragedy, but that figure does not represent the pain that Salem went through when she discovered that a school friend was among the dead.

“They found him dead eventually and in the hospital,” Salem says. “He became a really big martyr symbol because he was the youngest person to die.”

This friend was part of the reason behind Salem’s decision to protest against Morsi’s regime.

“It was one of the things that kind of shook me a lot because that guy, although we weren’t best friends, I knew him,” Salem says.

June 30 of this year sticks out for Salem as one of the most memorable days this summer. It is the day that protests began against the Muslim Brotherhood, the party in power.

Salem, along with a friend, took a taxi cab to Tahrir Square, but were stopped short when the cab faced a wall of people surging forward toward the square, the epicenter of the protests. Going an alternate route, the pair made their way down a street packed with people on all sides, buying flags and posters to hold up.

According to Salem, groups of protesters often clump together and start chants that echo across the entire square. At one point, she herself began a chant that was picked up by the people around her.

“We all had hope that we were going on for the same cause,” Salem says.

On the second day of protests, Egyptian Army Chief Gen. Abdul-Fattah el-Sisi faced the Muslim Brotherhood with an ultimatum: The government would either meet the demands of the people within 48 hours, or the military would depose the ruling party.

“Some people were skeptical definitely because we have seen very bad things from the military,” Salem says. “During the 25th of January revolution they killed a lot of people, they shed a lot of blood.”

This thought was in the back of many people’s minds, but many others, including William, who has family in Egypt, believe that without the military, the situation could have escalated even further.

“If he [Morsi] did not step down from power, the protesters would have not left,” William says. “More people would have died, so essentially the military took action to save their citizens.”

Despite the many differences in opinion concerning the military’s direct attack on the Morsi presidency, many Egyptian people were given a new hope of unity.

“[I thought] if the military ousts the Muslim Brotherhood this is going to be a uniting thing, the Egyptian people are going to have more trust and faith in the military once they take out the Muslim Brotherhood,” Salem says. “It’s going to be a positive thing, it’s going to unite us.”

This hope turned into a reality when on July 3, after the 48 hour window, el-Sisi declared that the Egyptian military would assume control over the government and suspend the constitution until early elections could be held. Removal of Morsi started bloody conflict between the supporters of the Muslim Brotherhood and supporters of the army, a conflict that still rages today.

Again, Salem and her friends traveled to Tahrir Square and celebrated along with other military supporters, while Muslim Brotherhood supporters gathered in Rabaa, a different area in Cairo. Soon, supporters of the Brotherhood took to the streets and began tagging buildings and burning down churches. William’s own church was defaced by Muslim Brotherhood supporters, but these extreme acts are in no way representative of supporters of the Muslim Brotherhood as a whole, according to Salem.

Despite Salem’s liberal leanings and anti-Muslim Brotherhood stance, Salem’s father, a Muslim Brotherhood supporter, convinced her to visit the main stronghold for those in support of the Muslim Brotherhood at Rabaa.

Stereotypes perpetuated by anti-Muslim Brotherhood protesters claimed that Rabaa was an unkempt, even disgusting place, according to Salem, but when she arrived, she found a modern headquarters. Some supporters had their laptops open and plugged into sockets in the wall of the building.

Salem believes that the military has retaliated too harshly against the Muslim Brotherhood and their supporters, many of whom are like the people Salem found in Rabaa.

“They [the Egyptian military] took out any political holding office person who was part of the Muslim Brotherhood,” Salem says. “I don’t like the political philosophy they [the Muslim Brotherhood] have, but that’s their right and they shouldn’t be punished, this is not democracy at all. It’s just ridiculous what they [the military] did.”

The military took its actions a step further when they encouraged Egyptian news channels to publicize the names of politicians who were members of the Muslim Brotherhood.

“They’re looking for them to basically jail them,” Salem says. “They didn’t give any reasons, the reason they gave was they’re accused of promoting violence.”

Newspapers and news channels run by the Muslim Brotherhood have been shut down since June 30 when the military closed many of their offices, leaving the Egyptian people without the voice of a major political party.

“You didn’t hear any of the Muslim Brotherhood opinions, you didn’t know about them,” Salem says. “The only channel that you could watch that you could actually see Rabaa was Al-Jazeera, because Al-Jazeera is a Qatar channel, but [on] any Egyptian channel, it was wiped out.”

For Salem, these actions do not represent the democratic government that Egypt deserves. Elections are the only answer for many, but the question remains of whether or not Morsi would have the opportunity to be re-elected despite widespread distaste for his past actions in office.

“They said … if he came in through a ‘box,’ he should be out through a box,” Salem says. “You really don’t want him, okay, let’s have an election and see who wins.”

Re-election of Morsi may seem like an outlandish proposition to some, but according to Salem, many of Egypt’s citizens are uneducated and easily swayed by the religious appeal of the Muslim Brotherhood.

“The majority will be for Morsi, but part of that majority, they’re not even educated,” Salem says. “They don’t know anything about politics, they don’t know anything about the Muslim Brotherhood, all they know is that its religion, so they’re going to do it.”

The military has become a state within a state, according to Salem. The military owns its own advanced hospitals while the people are forced to wait in long lines for treatment. Military supermarkets are well-stocked, while the shops dedicated to the people are often barren.

“I’m strongly against the military — for them to kill people who are peacefully protesting, to spray them and try to disperse them,” Salem says. “They’re just killing random people who are just protesting peacefully, it’s terrible.”

Egypt has been struggling to create a democratic government for the past three years, but as the military seems to gain greater control over the population many are unsure of what is truly best for the country.

“The situation has just gotten so complicated. If you had asked me in 2011, I would have been able to answer — Mubarak is going to be toppled, and we’re going to have democracy — but right now, the situation is just so complicated,” Salem says. “The military is really overpowering, they are not going to give up their power that they have had for a really long time. They used people to get what they want”

The events in Egypt are complicated and controversial, but for Awadallah, the goal is simple.

“Egypt … should have a way for the whole country to be listened to,” Awadallah says.

Media coverage in America fails to report the true extent of the happenings in Egypt, according to Awadallah.

“What people in America are being exposed to isn’t really what’s happening in Egypt,” Awadallah says. “A lot of people here are in support of the Muslim Brotherhood … and they’re [the Muslim Brotherhood] not telling the US what they’re actually doing, they’re actually doing much worse. To keep it simple, they’re [the Muslim Brotherhood is] lying.”

Ever since the Camp David Accords, Egypt has been one of the most important countries in the Middle East, from the American point of view. Aside from the $1.5 billion given to Egypt every year by the United States, the U.S. also supplies the country with weapons, including tanks, some of which were used against protesters.

“I think at this point a lot of the violence has been really troubling to the United States,” says Palo Alto High School’s foreign policy teacher Adam Yonkers. “And because a lot of these tanks and weapons are U.S. made, and U.S. bought.”

Many of the members of the Egyptian army are also trained in the U.S. in military schools such as West point, according to Yonkers. This relationship is crucial to the stability of the Middle East and losing such an ally would be detrimental to U.S. foreign policy in the region. As a result, the United States has been slow to address the situation in Egypt. By labeling the uprising as a political transition rather than a coup, the American government is still allowed to give the country its yearly aid packages.

“I don’t support foreign intervention at all, because any foreign intervention would come with its consequences,” Salem says. “A lot of people, especially in the Middle East, think the U.S. shouldn’t be the world’s policeman… The U.S. has taken advantage before, and used up the land and stuff just like what happened in Iraq.”

According to Salem, the issue in Egypt should be solved by the Egyptians and the Egyptians only. A new round of elections would allow the country to take further steps along the road to political freedom and democracy.

But for some, the political instability has taught them a lesson.

“I think Egypt got what they wanted in a sense,” William says, “where they assumed the Brotherhood would do good to Egypt, being that a lot of them [Muslim Brotherhood] are Egyptians, but I think that we learned our lesson.”