Perplexing and ineffective might be the first words to come to mind when one thinks of the Palo Alto High School homework policy. In fact, one would not be too far from the truth if one thought the homework policy was intended to confuse everyone. When 78 percent of Paly students reported in a recent Verde survey that they are unaware of their homework obligations under the homework policy, there is a problem, and it isn’t with the students.

Perplexing and ineffective might be the first words to come to mind when one thinks of the Palo Alto High School homework policy. In fact, one would not be too far from the truth if one thought the homework policy was intended to confuse everyone. When 78 percent of Paly students reported in a recent Verde survey that they are unaware of their homework obligations under the homework policy, there is a problem, and it isn’t with the students.

This is the view of many Paly students and teachers who feel that the homework policy is far too vague. According to Paly English teacher Sarah Bartlett, there is no way that teachers, however well-intentioned, could know if they are complying with the policy.

As of now, the homework policy recommends seven to 10 hours of work per week for students not taking accelerated, honors or Advanced Placement classes. In late February, Supt. Max McGee sent out a document to students and teachers in which he specified the homework expectations should not exceed 15 hours per week for any student.

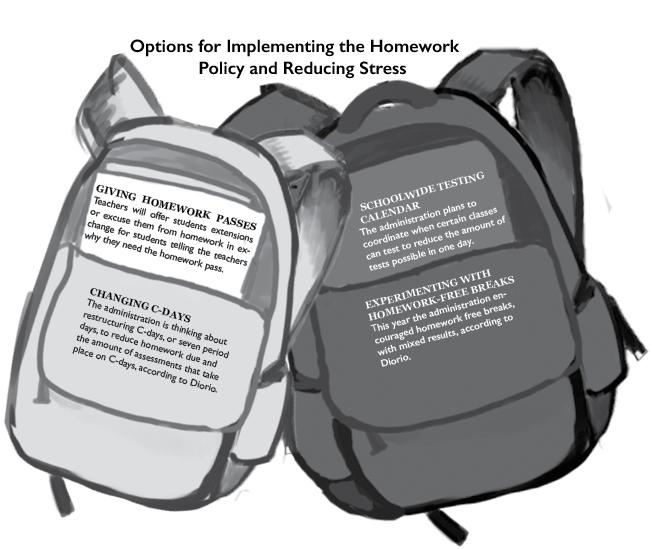

While Paly must abide by the district policy, the administration hopes to clarify how the homework policy should influence teachers’ decisions to assign homework. Parents, students and teachers have made several suggestions aimed at reducing student stress in light of recent events which have brought mental health and stress to the forefront of the community discussion. These proposals include reducing the number of AP courses students may take, expanding the course catalog to adequately reflect class difficulty, implementing a school-wide testing calendar, and minimizing student stress on seven period C-days.

The Problems

The main issue with the homework policy is that it never clarifies exactly how much homework teachers are allowed to give. The homework policy places a limit on homework for students in regular lane courses, however, there is no clear number given when a student is taking honors, AP or accelerated courses, as the policy simply states that those students “should expect loads higher than those outlined above [for regular lane classes] and should refer to class catalogs for homework expectations.” Teachers such as Bartlett argue that this lack of specificity makes the policy impossible to follow.

“If you were to ask a teacher, ‘Are you in compliance with the policy?’ I don’t think I could answer that question,” Bartlett says. “How much homework am I allowed to assign? … It depends whether a student has five classes or six classes or seven, whether they’re taking AP classes or not AP classes, it depends whether they’re a freshman or a senior. I think it’s unfair to fault teachers for not following it when no one can even figure out what it’s even saying.”

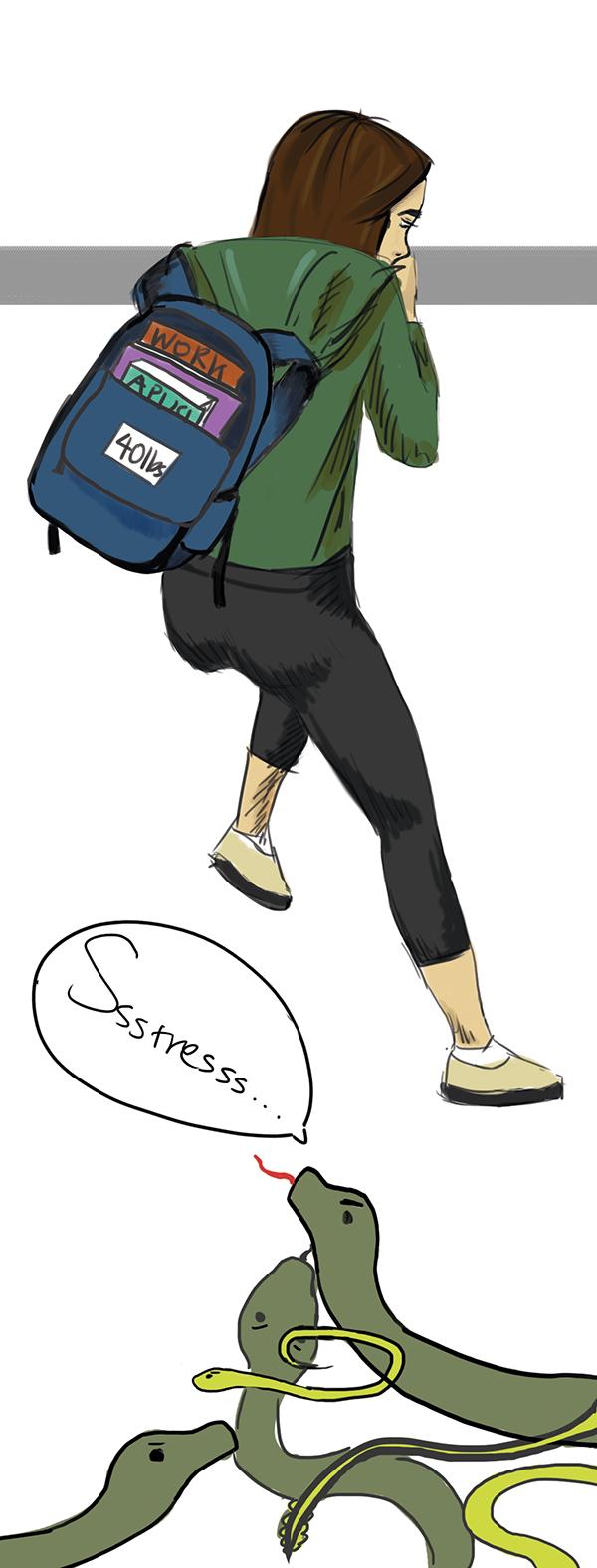

The lack of understanding of the homework policy extends to students, which can lead to students being swamped in homework that they weren’t expecting.

“The issue would be clarity,” senior Wesley Woo says. “People bite off more than they can chew, [and] especially for people in sports, you want to be able to rigidly manage your time, so specificity is key.”

Paly students experience high levels of stress, which the administration has been seeking to reduce this year. Despite efforts to curb student stress, 16 percent of students report that they have 15 or more hours of homework a week. Meanwhile, 37 percent of students report that they get six hours or less of sleep a night. The Western Association of Schools and Colleges data reports similar numbers.

“When we did our data through WASC, we heard loud and clear that [students] have on average anywhere from two to five or six hours a night of homework,” Paly Principal Kim Diorio says. “We learned … from talking to many students that they were spending a great amount of time on the weekends, Saturdays and Sundays, working on homework, not allowing themselves a break at any point during their week.”

The clause exempting AP and honors classes from the homework policy restrictions merely increases that stress, according to Diorio.

“It’s left a lot of room for interpretation in terms of giving time guidelines or quantity guidelines for students and teachers, and that’s been a detriment to our students,” Diorio says. “I believe we need to look at … the purpose of homework and have some conversations around best practices when it comes to homework.”

As the WASC process ends and Paly begins to discuss solutions for the problems that have been identified, the homework policy is drawing a lot of suggestions from students, teachers and parents alike.

The Course Catalog and Selection

The first item that people identify as needing improvement is the Paly Course Catalog, a compilation of Paly’s courses from which students select their schedules for the upcoming year. Only a quarter of the courses in the course catalog publish expected hours of homework, which makes planning more difficult for students.

The first item that people identify as needing improvement is the Paly Course Catalog, a compilation of Paly’s courses from which students select their schedules for the upcoming year. Only a quarter of the courses in the course catalog publish expected hours of homework, which makes planning more difficult for students.

According to Bartlett, putting homework estimates from the perspective of both the teachers and the students would be beneficial to the students.

“Sometimes there’s a difference between the teacher’s intention and the student’s experience,” Bartlett says. “So to try to get the teacher’s intention and the student’s experience to be more similar and then to actually publish that in the course catalog would help kids so at least they know what they’re getting into.”

Sophomore Candace Wang agrees that teachers should improve the course catalog.

“I get an estimate of the amount of homework I will receive the upcoming year during course selection through word of mouth mostly,” Wang says. “I think the course catalog should be less generic and have each course give an accurate measure of the time spent [for each].”

Diorio notes that several proposals call for revisions to the course catalog which would reduce stress around course selection. Suggestions include making the course catalog more multimedia[-based] and adding example assignments or projects to inform students about each class.

Additionally, course selection has been the focus of many discussions surrounding the homework load at Paly. This year, the administration placed a nonbinding maximum recommendation of two AP classes to try to reduce student stress.

“I want students on this campus to be having fun, getting sleep, taking care of themselves, and it sounds like when you have more than two APs it’s really hard to do those things,” Diorio says. “We really want students to hear loud and clear that by choosing to take more than two APs, you are setting yourself up for most likely not getting enough sleep at night.”

Although some in the community feel that APs should be limited, others believe that this would limit student freedom. Woo notes that there is a discrepancy in the difficulties of different AP classes, so a limit on AP classes may not be effective.

“Not every AP class is the same amount of work; not every AP is the same level of difficulty,” Woo says. “My idea was to rank APs in terms of a point scale or something and instead of limiting the number of APs … all your classes have to add up to a certain number of points, or all your AP classes have to add up to a certain amount of points.”

For example, AP U.S. History is known as a very demanding AP course, with several hours of homework per class meeting. Foreign language APs, in contrast, focus more on practicing the language in class rather than assigning out of class work. Thus, the amoun t of homework assigned by foreign language APs is typically far less than that assigned in AP U.S. History.

t of homework assigned by foreign language APs is typically far less than that assigned in AP U.S. History.

“The New Deal” for Students

Paly’s administration has experimented with several new ideas this year and hopes to help improve the implementation of the homework policy at the school. Although the Paly administration cannot change the text of the homework policy, it is charged with the implementation of the policy.

“My job is to make sure teachers and staff members are following the policy and upholding the policy and making sure that it has been communicated to students and parents and teachers alike,” Diorio says.

Data collected from students this school year and in future years will influence the implementation of the policy.

“We’re trying to … collect some data on just how many hours or how much time students do spend in a particular course or subject area on the homework,” Diorio says. “We need our students to tell us how much time they’re spending, what’s working [and] what’s not working so we can make adjustments.”

Bartlett agrees that student feedback is essential for informing teachers of the necessities of reforming and adapting their policies. Right now, she argues, there is a disconnect between the teacher and the student.

In order to gather more student data on homework and stress, Diorio plans to administer two surveys in the spring: the Hanover Research Survey and the Challenge Success Survey. These surveys will continue to be administered periodically to provide feedback on what is working and what is not.

Diorio hopes to continue experimenting with new policies and options at the end of the school year and into the next school years.

“I think as a school system we tend to be really stuck in the status quo, and I think right now we are moving toward this idea that we should really try some new things,” Diorio says. “Let’s see what happens and then if things don’t work out as planned or if it’s a fail, we learn from our mistakes and start over. It’s just like what we want kids to do — learn from your mistakes.”

The student poll results collected for this issue are from a survey administered in Palo Alto High School English classes over the course of several days in March 2015. Eight English classes were randomly selected, and 167 responses were collected. The surveys were completed online, and responses were anonymous. With 95 percent confidence, the results for the questions related to this story are accurate within a margin of error of 4.69 percent to 6.15 percent.