7 a.m. — Lisa Hao woke up, brushed her teeth, got dressed, ate breakfast and went to school just like she did every other day of her senior year in 2015.

10 a.m. — a police officer who was present for a fire alarm had overheard her friends expressing their concerns about her well-being, and ordered her to be placed under a 5150, an involuntary psychiatric hold. She was whisked away in an ambulance to an emergency outpatient center in San Mateo County to be evaluated and placed in a hospital.

10 p.m. — They couldn’t find a hospital bed for her, because she was seventeen and living in a county without adolescent-designated beds. She had been under emergency custody for 12 hours before being transported to Fremont Hospital in Contra Costa County, where she spent the remainder of the week as part of a teen inpatient hospital program, which provides intensive treatment within a secure environment for a variety of circumstances and which requires wards for patient housing

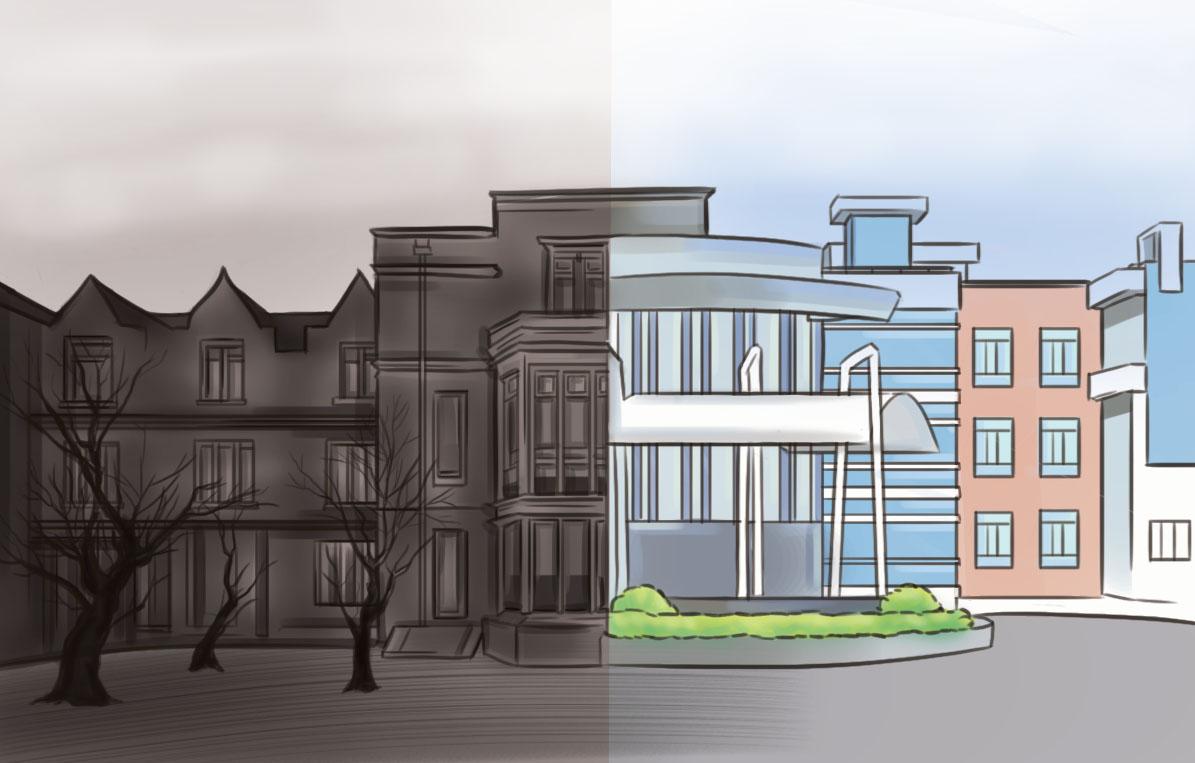

The time that Hao, a former Gunn student, spent waiting to be transferred to a hospital illustrated how students facing emotional crisis often received inadequate support due to a lack of accessible hospital beds designated specifically for adolescents.

Indeed, following a series of local suicides that occurred in 2013 and 2014, it became increasingly apparent that hospital beds for teens in the Bay Area were ironically absent in an area where mental health issues are disproportionately prevalent.

After years of working towards solutions, Santa Clara County signed an agreement in February with the San José Behavioral Hospital. The ward has opened in August of 2016, but the agreement will provide specifically for patients with commercial insurance in wards designated solely for adolescents needing psychiatric services.

The need

County Supervisor Joe Simitian, overseer of District five of Santa Clara County which encompasses the greater Palo Alto area, has been working towards bringing more teen beds to the area for about two and a half years.

“It came to my attention that there really wasn’t a place, a secure facility in SCC that provided acute care for teens who were at risk of doing harm to themselves or possibly others,” Simitian says.

According to the California Hospital Association, as of November 2016, only 13 counties out of the 58 in California had acute care psychiatric beds for adolescents. Until recently, the Santa Clara County was not one of the counties with dedicated teen beds.

“The concern is that on any given day there probably are 20 young people in SCC who need a secure care facility, a bed, in a secure environment,” Simitian says. “That doesn’t sound like a lot, but when you realize that typically stays in this situation are about a week for every one of those kids — you’re talking times 50 weeks — [then there are] literally several hundred if not thousands of families who have this need.”

While the county does have 166 beds set aside for adults, and an additional 40 beds for general psychiatric care, San José Behavioral Hospital is the first in the county with a ward designated solely for adolescents age 11 to 17, and is the first hospital to provide care covered by commercial insurance.

“Until recently that meant that here in the county we were sending kids as far away as Sacramento, Sonoma, San Francisco, Fremont over in Contra Costa county,” Simitian says. “Even if somebody had commercial insurance, the most convenient place was Mills Peninsula Hospital up in central San Mateo County.”

Hao was one of the patients who went out of county to receive inpatient care. From the time she left for evaluation to the time she was checked in at Fremont Hospital, she had spent almost 14 hours in transit.

Hao says she found the quality of patient care at Fremont Hospital to be subpar, unhelpful and unconducive to her recovery. In her opinion, the lack of beds and resources result in a system that aims to release patients as quickly as possible, rather than provide quality care and support.

“The goal is just to get discharged even though you’re supposed to be recovering,” Hao says. “Above all there just needs to be more funding and resources.”

James, a former Paly student whose name, like all others in this story, has been changed to protect his identity, was also taken into a hospital. James was checked into the county’s Emergency Psychiatric Care in San José, a facility that, at the time, did not provide inpatient beds for adolescents, but did provide 24-hour care.

“I think the place itself was fine, but the process needs to be improved,” James says. “I think there are certain ways to speed up the process, like making sure there are enough doctors. I wasn’t even there for a full day; I can’t imagine people that have to be there for days.”

Jess, another Paly student, had to wait several hours for a teen bed to become available before being checked into a hospital for her depression.

“You don’t get immediate care, there’s a long process, and you’re waiting to be transferred, and you could be transferred to multiple different places because they don’t always know how many people are coming in at all times,” she says.

Although the problem is being addressed now, several factors have affected the ability of the county to provide such beds.

“As painful as it is to say it, money is part of the problem,” Simitian says. “This is expensive care to provide, and if you’re trying to persuade a particular hospital or medical organization to provide this service, the first question they’re going to ask is ‘How are we going to pay for it?’”

In addition, the need to provide inpatient services for adults has meant that adolescent needs have been undervalued in comparison. “It’s certainly less than ideal when you’re pitting adult health needs against teenage mental health needs,” Simitian says. “That’s not good for anybody.”

The big picture

Although Simitian has been pushing to partner with hospitals in the county, the beds are only a small part of the ongoing discussions needed to improve the way that the county deals with mental health.

“I understand that the beds are part of a larger continuum of care, and have been working on that piece of it as well,” Simitian says.

Steven Adelsheim, a clinical professor at Stanford who works in early detection and prevention of teen mental health crises, has been working toward improving the front end of the continuum — care and prevention of mental illness.

“I think we do need inpatient hospital beds, but I also think that we need the front end of the continuum at least as much, and we don’t really have that very well,” Adelsheim says. “I’ve been concerned for most of my career about the lack of parity of the service in relation to physical health services, and the lack of equity in terms of being able to access the needs that there have been for other physical health conditions.”

According to the American Psychiatric Association, 50 percent of mental illnesses arise before the age of 14, and 75 percent by the age of 24. Often teens and their parents are not able to self-diagnose themselves and therfore are unable to get the initial support they need.

“As a result, by the time they access services, very often their issue has progressed to a very serious point of where they require a much higher level of support and services, or even crisis intervention or inpatient stays,” Adelsheim says.

Moving forward

The agreement made with the San José Behavioral Health Hospital would allow patients with commercial insurance to have access to 17 adolescent beds in the county; the ward opened in August of 2016, but the deal with the county was only signed early this year.

“I think that [it] is a significant step forward,” Simitian says. “But, it’s still not terribly convenient to a lot of the families that I represent in northern Santa Clara County; it’s in south San José, it’s still a long haul, particularly for families who are trying to see their kids at the end of the day, rush hour traffic, all of that.”

Adelsheim and a team of other psychiatrists have been working with the county and the district to provide support earlier on.

“I think there’s been really good work at Paly focusing on breaking down the stigma through [Paly clubs] Let’s Bring Change to Mind and Sources of Strength,” Adelsheim says. “[These programs] are important in terms of helping young people feel more comfortable getting early mental health care, they’re important in terms of helping young people recognize early warning signs, and they are important in terms of helping young people know what to do when their friend’s distressed, and to get them the sort of services.”

Simitian acknowledges that there is still a lot to be done. “It’s a good first step, but it’s only a first step, and we still need to do more,” he says. “I am particularly anxious that we do more in a location that’s going to be convenient for families in central and northern Santa Clara County.”

It’s a good first step, but it’s only a first step, and we still need to do more. — JOE SIMITIAN, county supervisor

Their stories

“Do I have to go?” Gunn High School senior Lisa Hao remembers pleading to a psychiatrist. “Is there any way I could not go?”

“I’m sorry,” she recalls a psychiatrist telling her in an unsympathetic monotone. “But this decision was made before you got here.”

Moments later, Hao was taken against her will to a transitional center, before an ambulance transported her to Fremont Hospital.

“You guys didn’t even wait to see how I was actually doing,” Hao recalls thinking as a police officer whisked her away to the hospital where she would stay for the next three days.

“I knew I was supposed to be getting help,” Hao says, “But I didn’t know what that would be or that I would stay there for three days.”

Hao knew almost immediately that she did not belong at the hospital.

“The only thing that helped me was that I hated it so much I knew I never wanted to go back which helped me take steps in the right direction.” Hao says.

After a concerned friend reported him to a Paly administrator the winter of his junior year, James was taken to the facility and made to wait hours to see a psychiatrist.

During this time, James was forced to witness adults violently screaming at police officers and begging for drugs.

At the hospital, it seemed to James as if all the doctors were not giving their full attention to each patient, and the lack of communication from staff left many scared patients in the dark.

“There is a lot of waiting around for people and uncertainty of what’s going to happen,” James says.

Much like Hao, James feels that the biggest takeaways from this experience were his internal realizations, rather than the actual medical care that he received.

“I think my reaction was, ‘This isn’t me, I don’t belong here and I didn’t belong with this people,’” James says. “But then I was also like, ‘You may not want to belong with these people, but you are here for a reason and you’re here to get help and this is the beginning of not demeaning yourself as a person but of using this experience as a wake-up call to realize how blessed you are.”