The theater darkens, and an air of anticipation fills the room. All that can be heard are the clicks of the projector as the screen is illuminated. With an ornate border around the stage, jaw-dropping chandeliers in the lobby and a gleaming organ, the atmosphere transports patrons back in time to the golden age of film: the 1920s.

Although the landscape of Palo Alto has changed tremendously in the last century, for the Stanford Theatre — which still uses the British spelling of the word — time has stood still thanks to the tireless effort of manager Cyndi Mortensen. Mortensen has worked at the theater for almost three decades and knows every detail about its intriguing history.

Mortensen explains that the theater was built in 1925, at the height of the glitz and glamour of the roaring 1920s, and stood proudly as one of the largest and most popular theaters in the area at the time. It was dubbed the “Pride of the Peninsula” by the Palo Alto Weekly when it first opened, attracting movie lovers from around the Bay Area.

According to Mortensen, one of the biggest attractions is the theater’s beautiful Wurlitzer organ, which has been restored and is still in use today. Back when all films were silent, organists would play during the films to enthrall audiences with musical ambiance or dramatic emphasis.

“Most movie theaters in the silent era had either a Wurlitzer organ and some of them actually had an orchestra,” Mortensen says. “There was always somebody playing live music to go with the silent film.”

In the 1930s, once “talkies,” or films with dialogue, gained momentum, the organ was used in between films or during intermission as a kind of secondary show. It is now a regular part of the movie-going experience at the Stanford Theatre, Mortensen says.

Besides playing films, the Stanford Theatre used to host “vaudeville” shows: a popular form of entertainment from the turn of the century through the ’30s consisting of singing, dancing and comedic acts. Many famous actors started in vaudeville, including Ginger Rogers, who actually performed at the Stanford Theatre soon after its opening.

The theater operated as a movie house through the 1970s after which it was sold and turned into a live music and performance venue. This new venture was unpopular, so it was sold again and converted back to a movie theater. According to Mortensen, at this point the theater was run-down and musty, with rusty sagging seats and peeling paint.

Luckily, David Woodley Packard, son of David and Lucile Packard, came to the rescue. After the death of movie star Fred Astaire in 1987, Packard rented out the theater for the weekend to host a marathon of Astaire’s films. Enamored with old films and the theater’s history, Packard convinced his father to buy it through the Packard Foundation.

“They decided that they would completely restore the theater to the way it was in the ’20s,” Mortensen says. “Completely dedicated to classic film.”

Packard located the artist who first painted the ceiling murals in the auditorium, found the original architect’s plans and matched the paint colors to create the most accurate restoration possible. Even the films themselves are all shown through a reel-to-reel projector on 35-millimeter prints.

“What David has done is replicate the movie-going experience of the 20s and 30s,” Mortensen says. “So when you come in here, you’ve virtually done a little time travel.”

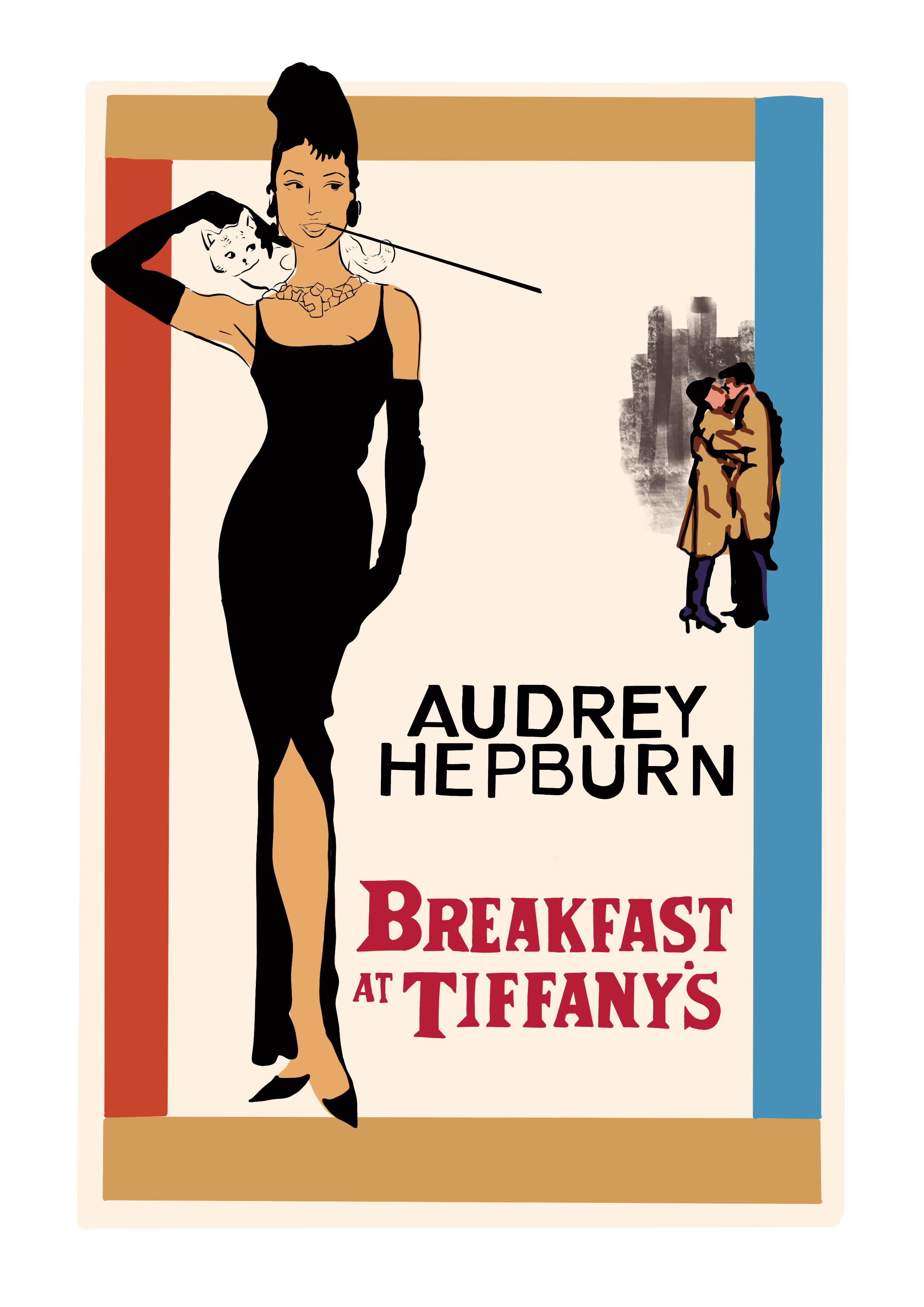

Mortensen works closely with Packard, procuring the necessary prints of movie posters and creating the calendar after Packard decides on the program.

“That’s David Packard’s passion. He is the programmer here and he hasn’t steered us wrong,” Mortensen says. “He’s got very good instincts about what works and what people love, and generally they are things that he himself loves.”

The Stanford Theatre Foundation’s film archive contains hundreds of films, and the Stanford Theatre always strives to broaden its repertoire. Mortensen says she is constantly bringing in new films to their collection from resources like the UCLA film archive, the Packard Humanities Institute and the Library of Congress.

“I work very closely with film archives throughout the country and in the world to really make sure that we can bring the best prints available,” Mortensen says.

Unfortunately, as technology continues to improve and film prints become more obsolete, it becomes more difficult to find classic film prints.

“[35 millimeter prints] are becoming more and more rare and harder to come by.” Mortensen says.

Even so, for Mortensen, the past two decades have flown by, and she has hope for the future of the longstanding Stanford Theatre.

“I’ve always loved old movies and classic film,” Mortensen says, while admiring the gold decor of the historic Stanford Theatre. “This is the perfect thing for me to be doing.” v