The competitors weave about one another inside of the battle arena, each maintaining a safe distance from the other fighters while simultaneously looking for a chance to strike. Suddenly, one of the fighters lunges forward. Everything becomes a flurry of chaotic motion, lasting for an instant. The result is several of the combatants mangled on the floor, ending another match between members of the aerial fight club, known as Game of Drones, in their exhibition at the 2014 Maker Faire.

Game of Drones has paralleled the rise of drone technology, quickly growing from a small group of robotics enthusiasts to a well-established organization dedicated to improving drones through drone-on-drone battle.

Marque Cornblatt and Eli Delia, the co-founders of Game of Drones, believe that battling drones creates a unique environment for innovation, forcing participants to improve or be destroyed.

“I think the best thing that has come out of fighting drones is how fast we learned to develop,” Delia says. “I think that trial by fire as I call it is a fantastic methodology for finding what’s wrong with your drone as fast as possible.”

Cornblatt and Delia hope that through the unique conditions provided by Game of Drones, they can promote innovation in the wider drone industry, a field Delia predicts will become a ubiquitous part of civilian life.

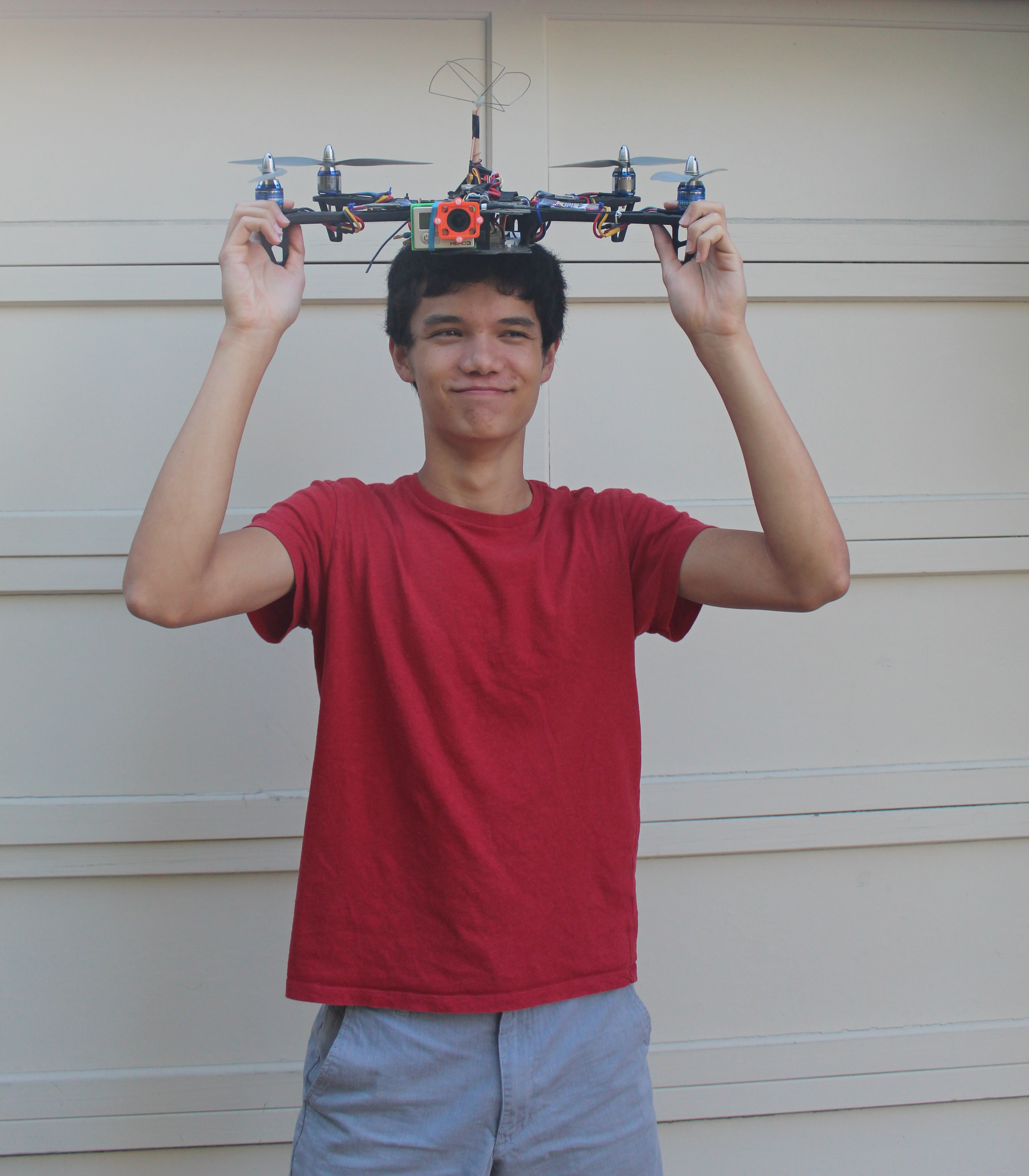

Palo Alto High School junior Nathan Kau holds a similar opinion. Through Kau’s internship at Matternet, a Menlo Park startup specializing in drone delivery technologies, he has gained first-hand experience into the rapidly expanding world of drone technology.

“I think the development of small drones will mirror the development of the personal computer,” Kau says. “Two years ago, personal drones were exclusively the hobby of tech enthusiasts. Now, personal drones are just reaching the consumer market. In two decades, we’ll barely notice the ever-present buzz of drones flying overhead.”

However, despite the perceived benefit of drone technology, many have less optimistic feelings towards the field, fearing that drones might put their privacy at risk through unwanted surveillance.

Cornblatt believes that while these concerns may seem legitimate, they are less so in practice.

“If you wanted to spy on someone, you could theoretically put a drone up with a camera and start spying on them through the window, but they would know,” Cornblatt says. “Drones are not a secretive or effective way of spying on someone.”

Delia attributes the public’s fear of drones to military use of the new technology, as well as what he sees as knee-jerk regulations made against the drone industry by the Federal Aviation Association. “I believe the FAA is overstepping their bounds in an area that is brand new to them,” Delia says. “However, there are enough of us developers that are pushing back that we’re going to have the freedom to continue forward.”

In fact, consistent with Delia’s prediction, drone technology made a significant step forward recently. Acknowledging the utility of drones, videographers, agribusiness organizations and oil-production companies have lobbied against the FAA, hoping to lift restrictions against using drones in national airspace. As a result, on Sept. 25, the FAA lessened its restrictions on using drones commercially, giving select Hollywood movie companies permission to use drones on set. These exemptions may provide a precedent for future federal drone regulation, allowing drones to assume a more prominent role in people’s lives.

“It’s not humanity that’s going to be able to travel to the stars,” Delia says. “It’s going to be our machines.”