[su_animate type=”fadeInUp” delay=”0.5″]To read to the story translated in Spanish, click here[/su_animate]

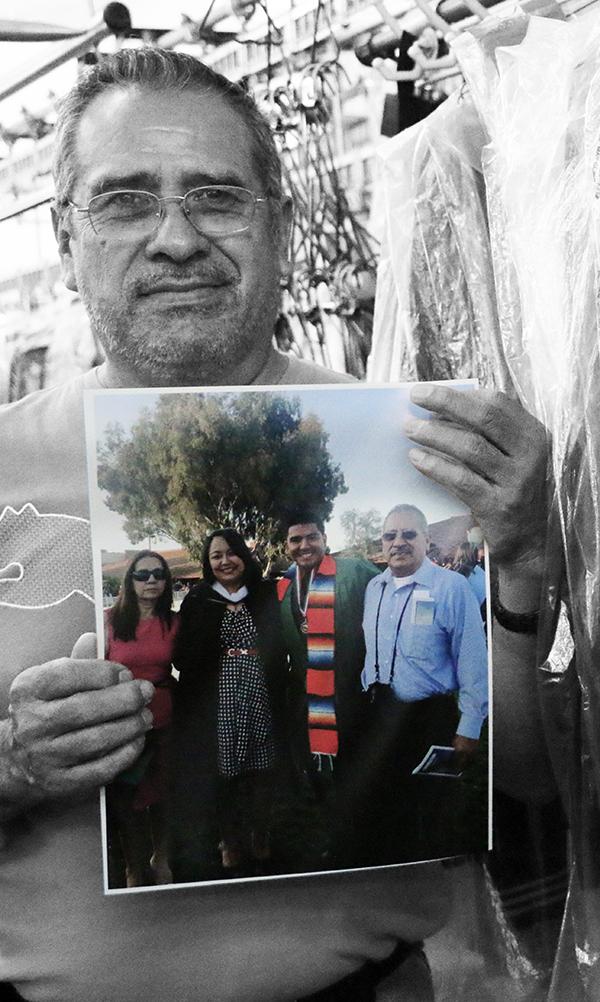

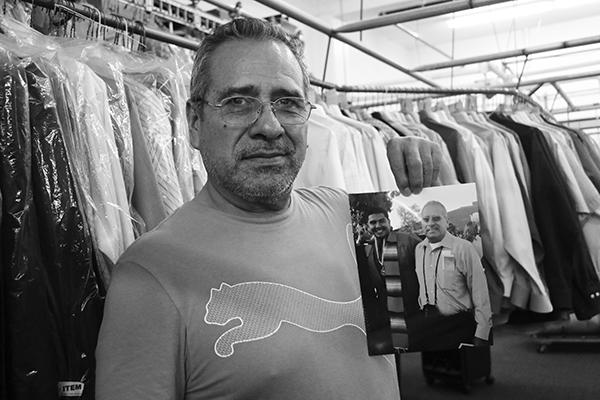

There’s a reason why Jaime Torres arrives at the Holiday Cleaners in Midtown Palo Alto at 4 a.m. each morning when the stars are still out and the parking lot is empty. There’s a reason why he’s worked this shift at the dry cleaning store for the past 20 years, and no, it’s not just for the sake of the hard work he learned to value back home in Michoacan, Mexico — where he started harvesting corn at age five, leading him to drop out after fifth grade to help put food on the table. It’s not just for the $1,500 he sends back to his parents and in-laws each month. Jaime will tell you that he enjoys his work and likes being able to contribute to the community, but it takes something deeper for a man to do what he and his wife Josefina have done these past decades.

If you ask him why — why does he really do it? — he’ll stop sorting through the dirty dress shirts, set down his detergent, and look you right in the eye.

“Para mi hijo,” he’ll say. For my son.

Jaime has six kids, (the oldest is now 42) and five were raised by his ex-wife back in Mexico, all dropping out of high school to work, just like their father had. Yet when Jaime came to America, met Josefina and had his last son, Jose, he knew things could be different. He knew it when the El Carmelo Elementary principal took him aside and told him that his son was smart and could go to college.

“You have to be the one,” Jaime told Jose. “You have to get good grades and show your brothers and sisters.”

Friends and family would make passing comments — “He can’t do it, getting into college is too hard, and you wouldn’t be able to afford it anyway.”

And why should they have believed otherwise? Their families had tried and failed. From their perspectives, college simply wasn’t a realistic possibility. Jaime ignored them: “With sacrifice and effort, mi hijo, we will always reach our goal.”

So the years passed, as Jose managed his school work and kept his grades strong until finally it was senior year and college applications loomed ahead. It was a difficult time for Jaime and Josefina, who didn’t know English well enough to navigate the complicated application process. But their son, with the help of the college advisers at Palo Alto High School, was able to successfully apply, writing his essay about how his first visit to Mexico had opened his eyes to the poverty his parents grew up in.

That spring, the acceptance letters started coming in, one from Saint Mary’s, another from UCSB, then Fresno State, with Jaime even more excited than his son at each acceptance — eight in total. When Redlands, a small liberal arts school in San Bernardino, offered a $27,000 scholarship, Jose decided to commit, becoming the first in his family to enroll in college.

Why College Matters

In the 21st century, it has become increasingly necessary for first generation students like Jose Torres to take the next step by applying to a four-year college. This fact has not been lost on the Paly administration, which has been working to ensure that all first generation students at Paly have the means and resources available to continue their education after high school.

For the under-privileged in particular, college makes a big difference. A 2013 study by the College Board revealed that for students coming from families in the bottom 20 percent of the income bracket, 90 percent move out of this bracket after earning a bachelor’s degree compared to only 50 percent without a degree.

There is still a substantial number of students in the education system today who come from families without a college background. The College Board reported in 2011 that more than one-third of 5- to 17-year olds in the U.S. are students who could potentially be the first in their families to go to college. The upturn of going to college is now estimated to be $500,000, meaning that college graduates will ultimately earn an average of half a million more than those without a degree, even when tuition and student debt are factored in. But what does all this mean on a more personal level?

For Eriana Davis, college means the chance to have a career and not just a job. The chance to be part of a sorority and live in a dorm. The chance to do something that her mother, who had her first of five children at 16, could not.

For Adrian Guzman, it means providing closure to the question his parents always ask him: Would you rather be working in labor until you’re 60 or working behind a desk with an air conditioner?

For Lisa Rogge, a degree means the ability to raise her kids with more opportunities than she had.

For all of the 50 first generation students at Paly — approximately 10 percent of the senior class — going to college provides a chance at upward mobility for themselves and their families.

[slideshow_deploy id=’5235′]

The Support Network

Sandra Cernobori and Alice Erber are the only two college advisers at Paly, in charge of helping a total of about 1,000 upperclassmen apply to college. For many, the two serve merely as consultants, but they often provide the backbone of support for first generation students during the college application process, serving as their core source of information.

Starting sophomore year, each Paly student is assigned a teacher adviser who helps to guide them through the college application process. While advisories, in which the teacher meets with their class of 20 to 30 students, occur almost every other Thursday during the second semester of junior year, they taper off significantly in senior year, arguably the time when they are needed the most. Recognizing that this is not enough guidance for many first generation students, Cernobori and Erber have organized an informal first generation group which meets every two to four weeks to provide students with more hands-on support.

“It’s a self-referral process,” Cernobori says. “We’ve identified them and their parents and they are choosing whether or not to come.”

The First Generation Group

On a recent Thursday lunchtime meeting in the library, Cernobori and Erber prepare to review the process of applying for the Educational Opportunity Program, designed to improve access at California State Universities for low income and “educationally disadvantaged” students. Applying for an EOP isn’t easy because it’s more or less the equivalent of another college application, requiring essays, online forms and even interviews.

Today there is a record high of 17 students. Even though she sends out both emails and text reminders, Cernobori says usually only 10 show up. However, since the group is informal, there is nothing she can do. After everyone has settled down with the pizza provided by the counselors, Cernobori begins addressing the students:

“Show of hands, how many of you have at least started a UC or CSU app?” she asks. Most hands go up.

“How many of you do not have a finalized college list?” she continues. No hands this time. “Be honest.”

Senior Lisa Rogge cautiously raises her hand. “I might take take a few off,” she says. Now, more students raise their hands.

“Finalizing the list really needs to get done,” Cernobori says. “It needs to be done by next week. I encourage you to track the deadlines. Colleges that have a Jan. 1 deadline — the cover sheet [notifying the administration to send out transcripts] is due Monday. I don’t want you panicking, but there is a sense of urgency.”

The students nod.

“Today there is no senior advisory,” Cernobori says. “But I’ll be in the computer lab helping people. If you don’t know what you’re doing, come by and we can do it together.”

However, despite the best efforts of the college advisers, they are unable to help all the first generation students.

“I’m like a teacher that teaches five periods a day,” Cernobori says, referring to her daily appointments with students and the work that goes into coordinating college visits. “[The first generation group] is not part of my job description.”

Other schools, including crosstown high school Gunn, have a guidance counselor devoted solely to first generation students, a resource Paly lacks. Cernobori says that she would like to see a special advisory system put in place to better assist first generation students, though she acknowledges that it should still be optional.

The Outreach Specialist

Crystal Laguna never met with her high school guidance counselor. By her own admission, she was one of the students who fell through the cracks and only found out she was eligible to graduate the day before the ceremony.

In community college, counselors told her, “College isn’t for everybody, don’t aim so high.”

Being a first generation student and not knowing anyone else who went to college, Laguna figured they knew what they are talking about — maybe she wasn’t the “college type.” Yet she continued her education, went on to graduate cum laude from UCLA and later received a Master’s degree in teaching from San Jose State University. Now, she works as an Outreach Specialist at Paly. As a native Spanish speaker, she provides a crucial link between Paly counselors and Latino parents in hosting “Latino Parent information nights.”

“I want to be there for [first generation] students so that if they hear something negative, I can tell them, ‘You don’t need to follow that,’” Laguna says. “There is nothing wrong with aiming higher than you think you might be able to get to.”

Choosing Community College

Cernobori says that over 80 percent of Paly students go straight to a four-year university after high school. Although community college can be a viable option for the remaining 20 percent, Cernobori argues that a disheartening number of students in community college don’t ever end up transferring or completing their degree.

Some students look toward community college without considering a four-year university. When this appears to be the case, Cernobori and Erber ask them if they are willing to reconsider. Many times, a student simply doesn’t realize they are qualified to attend a four-year university, but for others, like senior Gloria Guzman, there are more complex reasons behind the decision to enroll in a community college.

“I was focusing on what other people wanted for me as opposed to what I wanted,” Guzman says. “Everyone thinks that a four-year university is best, but I want to pursue a different path.”

Since being baptized two year’s ago as a Jehovah’s Witness, Guzman has dedicated her life to serving God. She planned on attending a four-year university until last summer, when she began to question her motives and concluded that she didn’t want to be in a secular place where she might lose her faith.

There were other factors leading to Guzman’s decision. Her mother never talked about college until recently, after she realized that a high school diploma was not enough in today’s job market. Still, she never pushed her daughter to try hard in school and didn’t mind Cs on report cards, though Guzman did, and would tell her mother: “I’m not a C student.”

With her father out of the picture and her mother indifferent about academics, Guzman has become the support network for herself and for her younger brother and sister. She is the one who emails her brother’s teachers to make sure he is attending class and completing his work; she is the one who helps her sister decide which activities to sign up for; she is the one who makes sure they both have friends who are positive influences so that they will continue to emphasize education in their lives.

“I can’t leave my family,” Guzman says. “My mom takes care of the financial part, but I’m the one who grades my brother’s essays. I’m the one who tutors him in history and biology.”

Money is also a concern. Guzman knows many adults who went to a four-year university but no longer work in the field they majored in, and she worries that paying for a degree in something she might not use later is too much of a risk to take.

With all of these factors to take into account, Guzman plans to enroll in a nursing program at De Anza College but remains optimistic about eventually transferring to a four-year university.

“The amount of people who transfer [out of community college] is very low, but that is for people who are just exploring,” Guzman says. “I feel like I, on the other hand, know what I want to do.”

What the District is Doing to Help

In addition to the resources provided through the College and Career Center, the Advancement Via Individual Determination program has been put into place to serve as a resource for first generation students and those “in the academic middle” from the moment they set foot in Paly to the moment they graduate. The Paly administration sought to revamp AVID by starting fresh this year and putting veteran teacher Elizabeth Mueller in charge.

With the backing of the principal and guidance department, AVID has grown from a class of 19 students to 35 students, the majority of whom are freshmen, in part because of active recruiting from Palo Alto Unified School District middle schools last year. Mueller says she hopes to grow the number of students for future freshman classes while continuing to work with the Class of 2018 for all four years. As the number of students in AVID increases, Principal Kim Diorio says she wants to provide individual laptops for those in AVID. Diorio also plans to make Laguna a counselor specifically for the AVID students.

Opening Doors to a Better Future

Clarissa Valencia’s father dropped out of a local high school to support his family, and Valencia’s mother left school as a senior after she became pregnant. Her mother, a preschool teacher, fought to keep Valencia in the PAUSD, even when they lived in Hayward for a time. Now a senior, Valencia lives in a one bedroom apartment in Palo Alto with her mother, sister, stepfather and two stepsiblings.

Valencia figured that she would just go to community college after high school, but one-on-one meetings with Erber during junior year changed her mind. Now she goes to essay writing workshops and participates actively in the first generation group.

“The college and career counselors opened the door [to a four-year college] for me,” Valencia says.

Of her first generation friends, Valencia adds: “I know two other people who are motivated and doing the Common Application and going to the college workshops, but everyone else — though they are smart and capable — I feel they’re just not reaching out. It’s kind of a two-way thing where Ms. Cernobori and Ms. Erber will reach out and you have to meet them halfway also.”

Other resources exist for those who are willing to put in the effort, including East Palo Alto’s College Track program and the Foundation for a College Education. Still, it’s ultimately up to the students themselves to make use of these resources.

Out of all her friends, Valencia is the only one still going to the first generation meetings. She says that even though many first generation students have the opportunity to go to a UC or CSU, they don’t feel the need to go anywhere beyond community college because their parents and siblings never went further than high school.

“I don’t think you can force someone to want something,” Valencia says.

Valencia has inspired others in her family to also seek a college education.

“I have a cousin who is two years younger than me,” she says. “I was telling him I was working on my applications already, and he was really excited. He told his mom, ‘Clarissa’s going to be the first girl to graduate high school and go to college, and I’m going to be the first boy.’”

Setting the tone for the rest of the family is important: When Valencia was younger, she recalls her aunt and uncle making a bet that she would get pregnant before she was 16, as has happened with many other women in the family. But against expectations, Valencia has avoided following that path and is on track to enroll in a four-year college.

“Everyone I know that didn’t go to college, they are not living ideally,” Valencia says. “They are either depending on a spouse, or they don’t have any stable place to be, or they are living with their parents. To have a career, you have to go to college.”

We Stand on the Shoulders of Giants

There are certain times in a person’s life when they have the opportunity to transcend the moment through their actions. For Jose Torres, this moment was his high school graduation. That day, he gave a speech to the crowd of hundreds gathered to watch the Class of 2014 receive its diplomas. Sometimes not even the most eloquent of words can do full justice to the underlying emotions that they carry, yet Jose attempted to sum up 20 years of sacrifice by his parents in just one sentence.

We stand on the shoulders of giants.

For Jaime, seeing his son on the podium was the greatest satisfaction he’d ever felt in his life, and for Josefina, “su corazón no quedaba dentro del pecho de la emocion” — her heart swelled with emotion.

Every good teacher wants to make a profound difference in the life of a student, and Laguna, Erber and the others had done just that for Jose. I want to thank all the teachers and staff who believed in me and encouraged me to always do better … With their help, and the help of the staff in the college and career center, I am going to college.

If you were there that May afternoon, you would have remembered Jose’s speech as the one that drew the standing ovation and brought the speaker to tears as he spoke the concluding lines, addressed to his parents: A thousand thank yous for all that you have given me and all that you will give me in the future. Without you I would not be where I am now, and I would not be the man I am today. Te amo mama. Te amo papa.