Spring of 2021. Masked students sit in eerily quiet classrooms. The rooms lack life, with the few students there in person separated by clear plastic dividers and distanced by vacant desks.

Now, a year later, the scene looks oddly familiar. The transparent divisions are gone and masks begin to come off, but many blue chairs remain empty. With school entirely in-person for the 2021-2022 school year, however, this is not due to the district’s hybrid learning plans but is the result of one of Palo Alto High School’s greatest post-pandemic challenges — chronic absenteeism.

Over twice as many K-12 students across the nation have been chronically absent this school year compared to pre-pandemic numbers, according to a recent report by consulting firm McKinsey & Company. Palo Alto Unified School District followed similar trends this year — according to data from an Oct. 5 Board of Education meeting, 9.2% of students were chronically absent in Aug. and Sep. of this school year, compared to 5.55% of students in the pre-pandemic fall of 2019.

“Lack of access to health care, unhealthy environmental conditions, unreliable transportation, housing instability or the lack of safe paths to school, were creating barriers to getting to school before the pandemic and they still are barriers to being in school,” Attendance Works Director of Communication Catherine Cooney said. “The pandemic and distance learning has added nuances related to the barriers students and families face in getting to school, including economic stress and students feeling discouraged because they have fallen so far behind.”

Chronic absenteeism is defined by the California Department of Education as missing over 10% of instructional days, and is associated with long-lasting adverse social, academic and health consequences, according to an American Family Physician study, and its rise has prompted anti-absence initiatives such as mailing attendance letters home and reestablishing intervention meetings.

Anti-truancy triumphs

The renewed focus on attendance this year is a part of PAUSD’s Attendance Improvement Initiative, aimed at dropping the district’s chronic absenteeism rate below 5% across all racial groups and grades.

Paly’s current meeting system has four tiers of interventions with a different meeting after a student accumulates eight, 12, 24 and 40 unexcused absences. With each increase in the number of absences, the seriousness of the meeting increases — district administrators are present at the latter two meeting types.

According to research from Brown University’s Annenberg Institute, messaging to parents regarding how much school their child has missed — including these meetings and state-mandated attendance letters — can be extremely effective in reducing rates of absenteeism, especially when administrators actively follow up with students when attendance issues persist.

“I like the repeated follow up [of our process],” Assistant Principal Erik Olah said. “All through that pathway, … there are people that are checking in with the student.”

“We’re just trying to get the messaging out there and try to reestablish that it’s important for you to get to every class.”

— Erik Olah, assistant principal

PAUSD detailed in a recent report that they will be focusing its efforts on “historically under-represented subgroups” by connecting them with personal attendance coaches. Across PAUSD, Hispanic and Latinx students had a total of 1,183 unexcused absences while Caucasian students had a total of 989 unexcused absences, despite the fact that there almost three times more Caucasian students than Hispanic and Latinx, according to the district website.

“We already see a positive increase in attendance for students that have been connected with a student success coach,” Engagement Coordinator Miguel Fattoria said in an April 19 board meeting. “Our team has been working tirelessly with sites with schools with families, just to make sure that we see some sense of positive growth.”

Olah noted that new strategies to combat absenteeism this year are renewed attempts to address a longer-standing issue of poor attendance at Paly.

“When you look at the various schools in the area, we’ve always had more absenteeism than other schools,” Olah said. “We’re just trying to get the messaging out there and try to reestablish that it’s important for you to get to every class.”

Amending the attendance response

Though the anti-absence initiative is aimed at curbing unexcused absences and cuts, some students reported receiving attendance letters due to excused, often health-related, absences.

“I was sent a letter for excused absences which was surprising to me,” junior Sandhya Krishnan said. “I haven’t received any attendance letters in the past and when I looked at the letter, I didn’t really think my absences were that bad.”

Students receiving absence letters referencing health-based absences has raised questions regarding the intersection of this initiative with the COVID-19 pandemic — will efforts to increase attendance at school during these times lead to more students coming to school despite showing possible COVID-19 symptoms?

“In the past, students and staff who had what we thought were mild symptoms, would come to school in spite of them,” Paly nurse Jennifer Kleckner said. “With COVID though, we need to test and stay home, even if our initial test is negative because they so often convert to a positive.”

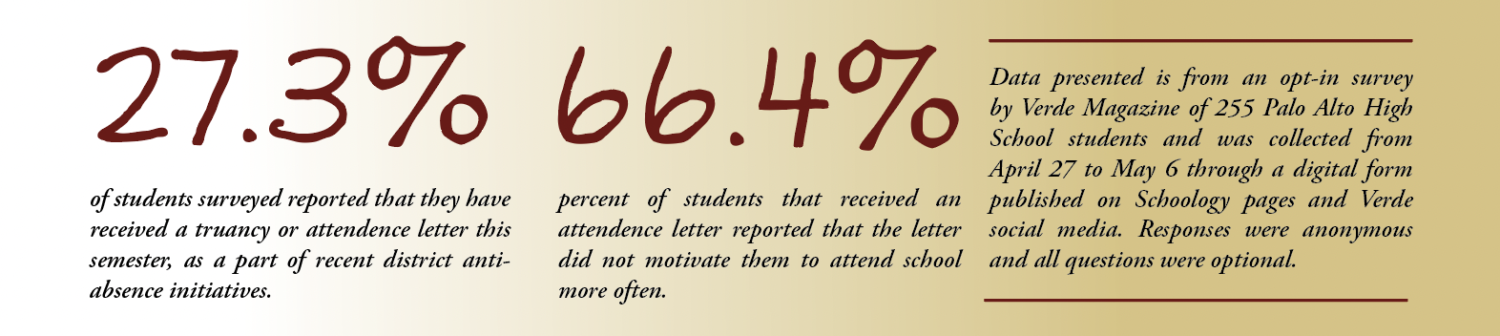

Furthermore, despite some reporting increased motivation to come to school after receiving an attendance warning, the letters themselves do not seem to be the most effective method of curbing absences for all students. According to an anonymous opt-in survey by Verde Magazine of 255 Paly students from April 27 to May 6, 66.4% of students who received an attendance letter say they are not more likely to attend school after receiving the warning.

“I’ve noticed that here at Paly, even though kids came back there, they feel disconnected. They’ve missed two years of getting to know your peers. I have students in my classroom who don’t know anyone else sitting in the classroom.”

— Debbie Whitson, teacher

Olah noted issues with the recent system of sending letters and emphasized how administrators are working to continually improve their system.

“Since about March or so, we’ve gone to a … different letter program where actually the letters are automatic,” Olah said. “It [the old system] was … not the best. The wording wasn’t quite where it needed to be and the thresholds [that warranted a letter to be sent] were a little low.”

Olah emphasized that attendance letters are a method of state-mandated intervention and not Paly’s main strategy to address absenteeism — that being the repeated attendance meetings that Olah and his colleagues have focused on this year.

“The letters are a state requirement, and that’s and there’s wording in there to make it clear that … that whole other intervention system that we use is not going anywhere,” Olah said. “So if you’re getting letters, and you haven’t had meetings before, that’s evidence that we’re not majorly concerned [about your attendance].”

Jumping “back in the game”

According to a recent report from the EdResearch for Recovery Project, low student engagement and poor student mental health are associated with absenteeism — both of which are factors that have increased since the onset of the pandemic.

“I’ve noticed that here at Paly, even though kids came back there, they feel disconnected,” economics teacher Debbie Whitson said. “They’ve missed two years of getting to know your peers. I have students in my classroom who don’t know anyone else sitting in the classroom, and that’s really unusual.”

English and humanities teacher Mimi Park said she has seen a cyclical pattern to absenteeism this year.

“I see students who miss a few classes and then they get even more worried about coming because they’re worried about the work they’re missing, how much it has piled up, how it will seem to other students since they’ve been gone so much,” Park said. “These students stop coming, which really impacts their education. At the same time, not being here means they can’t get help from their teachers, the tutoring center … to help catch up, so it doesn’t do them any good.”

I see students who miss a few classes and then they get even more worried … These students stop coming, which really impacts their education.”

— Mimi Park, teacher

Clinical Social Worker Eva Martinez mentioned that without having strong friendships as a result of the pandemic, students may be left without strong motivators to attend school. Martinez said the Wellness Center is aware of the mental health causes and effects of absenteeism, and is working to support students who need counseling during this emotionally difficult time.

Whitson said that though she understands the jump back to in-person learning may be difficult for many, students need to connect with their peers face-to-face within the classroom in order to learn at their best.

“You’ve got to jump back in the game and try to find engagement,” Whitson said. “Though students are connected online, without coming to school, there’s still a loss of ability to be connected really well. That’s very valuable.”