“I would never buy a German car.”

This was my father’s response when I asked him if I could get a tattoo. He then proceeded to tell me how my grandfather avoided German car dealerships because, during World War II, some of their manufacturers helped make weapons for the Nazis.

“It’s symbolic of my respect for my father,” he said. “Just as getting a tattoo would be disrespecting Jewish tradition.”

I have always wanted a tattoo: a unique form of self-expression to show off the fundamental parts of my identity. But while tattoos are becoming more popular with younger generations, in the Jewish tradition, they are still heavily frowned upon. In fact, ktovet kaka is the Hebrew term for tattoo, and the literal translation, “inscription of crap,” epitomizes this sentiment.

My father, the most religious in my family, describes tattoos as “aggressively non-Jewish.”

Many young Jews are deterred from permanently marking their skin with the warning that if they do so, their bodies will not be allowed in a Jewish graveyard. Although this misconception is not in the Torah, Leviticus 19:28 in the Old Testament indeed states “do not cut your bodies for the dead or put tattoo marks on yourselves,” rooting the fear of tattoos in biblical text.

In addition, Genesis 1:26 states “Then God said, ‘Let us make mankind in our image, in our likeness.’” According to retired Rabbi Ari Cartun, formerly of the Congregation Etz Chayim in Palo Alto, this means God created humans in God’s image. Therefore, our bodies are borrowed items that we shouldn’t permanently scar.

“I don’t want anything that I can’t change,” Cartun says. “And I think they [tattoos] are butt-ugly.”

“I don’t want anything that I can’t change. And I think they [tattoos] are butt-ugly.”

— Rabbi Ari Cartun

Even among secular Jews, there is a long-standing distaste for body art, as during the Holocaust, Jews were forcibly tattooed in concentration camps. Many Jews feel it is disrespectful to the six million who died, known only by the numbers tattooed on their arms, to voluntarily scar their bodies in the same way.

While I understand the validity in the Orthodox perspective because the text clearly states the forbiddance, I disagree with the restriction on tattoos.

The verses that condemn tattoos seem outdated and were likely written for health reasons, but as society and cleanliness progress, so should the rules of Judaism.

I also believe, contrary to the rabbinical explanation, that our bodies belong to us. They are not reused after we die, and therefore, I should be allowed to use my body as a canvas for self-expression.

And while I acknowledge the arguments for shying away from tattoos due to the atrocities of the Holocaust, Jews should take back the seminal part of their history with pride, similar to how the LGBTQ community reclaimed the term “queer” — originally an insult, now a commonly used all-encompassing term.

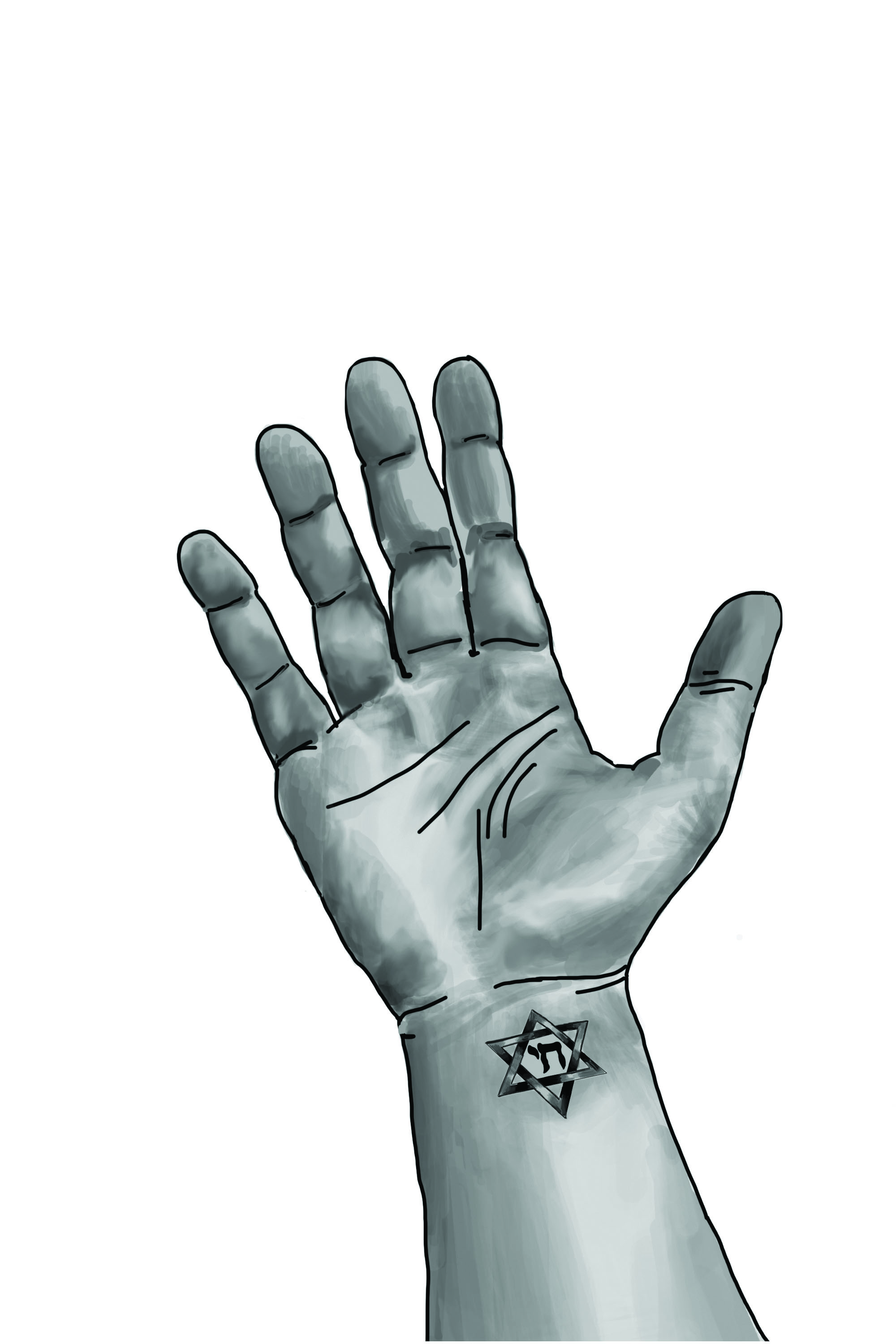

Young Jews should continue the traditions that make our culture unique, but we should also be allowed to evolve into a new Jewish generation: one that embraces self-expression rather than stigmatizing it. In fact, by getting a tattoo of a star of David or Hebrew letters, I’d personally feel more connected to the Jewish tradition, rather than distanced from it. I would have a reminder of my ancestry and history marked permanently on my skin.

Judaism is more than a religious doctrine. Judaism is cultural, biological and to some extent, racial — all Jews are descended from the initial twelve tribes of Israel. This means that being Jewish is a core part of my identity, and just as I will never escape criticism from the more religious of my family, neither will I escape my family’s history.

But my understanding of Judaism and my family’s past has only compelled me to want a tattoo, rather than driving me away from getting one. After all, as my father said, “you can’t decide you aren’t Jewish. It’s too integral to who you are.”