*Editors’ notes: This story originally referred to Sikh individuals as “Middle-eastern minorities.” This has been changed to “Middle-Eastern and south Asian minorities” to encompass Sikh individuals. All story corrections can be found under the ‘corrected stories’ tab.

Passing through security screenings at airports is already a lengthy process. We stand in line for what feels like hours, remove every possible piece of metal, from our dangling earrings to the clinking change in our pockets, and even double-check that none of our toothpastes or shaving creams exceeds 3.4 milliliters. An already frustrating experience is only exacerbated when we are pulled aside for the infamous random check.

While our saving grace is the infrequency of this experience, it is a disheartening norm for passengers who resemble Middle-Eastern and south Asian minorities. Such systematic profiling aligns with actions taken by the Trump administration, which has placed a travel ban against some majority-Muslim countries.

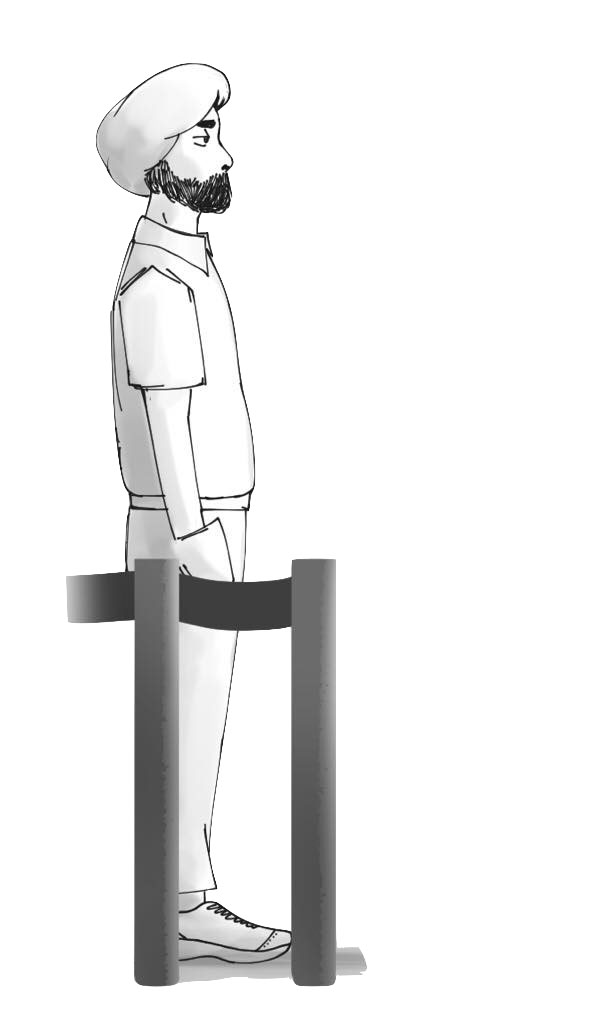

For many, airport security procedures feel like frustrating disruptions in an otherwise simple process of getting from one place to another. But for Palo Alto High School juniors Jōsh Singh and Sufi Kaur, both Sikhs of Indian descent, traveling through security is an altogether different experience.

According to the Transportation Security Administration website, security procedures are adjusted to address any evolving security threats by using random screenings to ensure the public’s safety. For Singh however, these screenings seem slightly too consistent to be random.

“I get checked almost every time,’’ Singh says.

For Kaur, the disparity is even more distinct. While traveling alone, she rarely draws a second glance. In stark contrast, when she travels with her father and brother, who both wear turbans, the family is often selected for random screenings.

“When I walk with my family, it’s like suddenly you become the family that gets pulled aside,” Kaur says.

While many in Singh’s position might be easily angered, he still maintains an open mind and considers reasoning from both sides.

“I don’t really want to protest the system because there is a reason for the system,” Singh says. “But I don’t think that doing it for only certain people is okay … I understand the fact that safety is very important and they do try to keep it impartial.”

While Singh regards the apparent racial profiling involved in random screenings as an irritant, he notes that the lack of understanding about his culture has other repercussions that impact him to a greater personal degree. The worst part about flying, he says, is the way children gawk at his dark skin and the colored fabric wrapped around his head.

“I go to the airport and see little kids looking at me with fear,” Singh says. “They’re scared of me because of the way that I’ve been portrayed and that’s ridiculous.”

Similar experiences leave Kaur feeling a different way. She pays little attention to onlookers because she knows that she hasn’t done anything wrong. Still, she sees it as a reflection of how she and others are victims of a disheartening system of generalizations.

“We obviously need to change something because it shouldn’t be this way,” Kaur says.

In the face of these challenges, some may rethink donning the cultural clothing that makes them stand out. But for Singh, his turban is his religion. It’s become a part of him.

“I’m not going to change my turban, my person, just to satisfy someone else.”

— Jōsh Singh, junior

“The greatest thing about this country is that we were founded on the morals that we can be whoever we are,” Singh says. “I’m not going to change my turban, my person, just to satisfy someone else.”

While Singh finds these experiences discouraging, he remarks that they are only results of lack of knowledge.

“Many of my friends have no idea who I am, what I stand for, and it’s crazy,” Singh says. “The worst part is that the textbooks that try to educated people on my faith get it wrong. They’ve said that we [Sikhs] are a sect of a religion. We’re not. We’re our own religion.”

And, for Singh, discrimination isn’t just limited to the confines of an airport. According to Singh, even in the hallways at school, some students at Paly make racist comments, yelling “Allahu Akbar” as he passes and asking what he would do if he were on a plane.

“They called me a terrorist,” Singh says.

Singh recognizes that these misconceptions originate from a lack of accurate information. The solution he sees to these issues however, lies not in retaliation, but in re-education.

“I think education is the most powerful tool ever,” Singh says. “Hate stems from ignorance. If we educate people, we create a better more accepting environment.”

Last year, Singh spoke in his Contemporary World History class to inform others of his culture and religion, in hopes of addressing the stereotyping that he and others have experienced.

Singh has reported incidents of discrimination to the administration, yet the process of working with the school has been slow. While Singh understands the challenges involved in administering discipline, he hopes the time it takes for the issue to be addressed can be shortened.

“It had to happen four times for anything to be done,” Singh says. “It isn’t the administration’s problem; it’s not the law’s problem either. They are trying to protect the other person as well. I just wish that it [the process] was expedited a bit more.”

Though Kaur has not experienced the same level of overt racism, she still worries for her family— especially her younger brother.

“I want to protect him from it [the racism],” Kaur says. “But I know that there’s nothing I can do other than try to be a positive person and … educate other people.”

While both Kaur and Singh continue to face racial discrimination, they hope that sharing their experiences will reduce the stigma that surrounds their identities.

“There is always room for change,” Kaur says. “We need to be tolerant and understanding of others.”