Upon first glance, Google’s self-driving car prototype looks a bit like a friendly lunchbox on wheels. Its headlights, front camera and turn signals form the eyes, nose and mouth of what looks like a gentle smile.

A closer look reveals several cameras adorning the front, rear and corners of the car. Even when idling, the car seems alert — machinery emitting a quiet whir as its sensors collect data to gain awareness of the roads, cars and humans of the surrounding environment.

The small tower of 360-degree sensors and cameras sprouting from the vehicle’s roof even has its own set of glass wipers. It’s clear that the car was constructed with the utmost attention to detail. “This is a vehicle that we have designed from scratch,” says Nathaniel Fairfield, a principle software engineer at Google’s self driving car division “[It] is self-driving from the ground-up.”

As of this August, ridesharing company Uber has integrated 100 new self-driving cars into its total fleet. Electric car company Tesla has also outfitted its newest vehicles with an autopilot feature, enabling the cars to drive themselves on freeway roads. Today’s cars are learning to drive — but so are millions of teens every year.

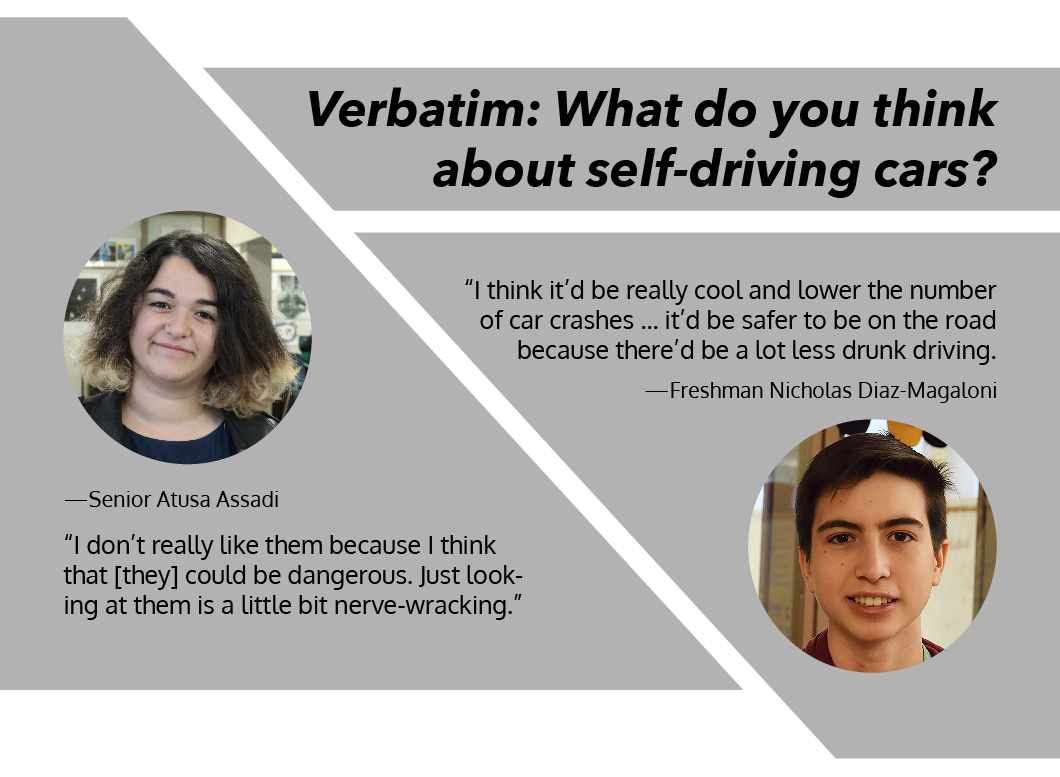

Self-driving cars are equipped to make America’s roads safer, but many teens are looking into an uncertain future. Some eagerly await a safer environment for transportation, but others aren’t ready to forfeit the control of driving.

Trusting the tech

While many remain optimistic about the technology’s potential to make teens safer, some teens question whether or not they can trust this space-age robot chauffeur to ensure their safety on the road. The juxtaposition of these two opinions poses many questions for teens who have recently received their licenses or will soon be receiving them.

More than 94 percent of car accidents are due to lapses in human judgment, according to Google’s self-driving car website. If human judgement can’t be depended upon, are machines our logical solution? To some, perhaps. But Nandini Relan, a junior at Palo Alto High School isn’t so sure.

Relan, who received her license in September, isn’t willing to give up her control at the wheel. “I don’t want to depend on the car — what if it stops working?” Relan says. “I like the idea of being able to drive myself and knowing that I’m the one in control.”

Paly junior Nicholas Zhao will be getting his learner’s permit soon and hitting the roads this fall as he learns to drive. While he shares Relan’s skepticism, he says future experimentation and tests of the cars might win his trust. Self-driving cars are ultimately driving computers, and Zhao says every computer has its glitches.

“I would wait and see the braver and the guinea pigs to first use them,” Zhao says. “Based on their results I’d be willing to use self-driving cars.”

Fairfield acknowledges this sentiment of teen trepidation.

“It’s a dangerous period of time to be driving,” Fairfield says. “You are learning to focus your attention on things, and a lot of collisions and traffic accidents happen.”

However, Fairfield has confidence that his technology will make a positive difference in the number of adolescents who are involved in traffic collisions, which, he hopes, will assuage the fears of skeptics.

“We can improve the safety of those [adolescent] years,” Fairfield says. “The important thing is to really really be sure that the cars are safe and well-behaved.”

Freedom from the wheel

Driving entails more than just getting behind the wheel and stepping on the gas pedal — it’s freedom to get to wherever you want, whenever you want, without having to ask your parents for a ride. Starting from a relatively young age, 16, this kind of independence liberates many Californian teens.

Fairfield says self-driving cars can extend this flexibility to all age groups and demographics — including those who may not be able to drive themselves places, such as children under the legal driving age, senior citizens or the visually impaired.

“We can improve the safety of those [adolescent] years.”

—Nathaniel Fairfield, Google software engineer

“This sort of tech promises to transform mobility for people,” Fairfield says. “People who couldn’t get around before or for whom transportation was cumbersome or expensive can now do so easily.”

If self-driving car technology functions as promised, nervous parents won’t need to worry about the safety of the roads, and consequently, the safety of their teens. Even if they’re suspicious of the cars, Fairfield notes that Google runs extensive safety tests on their prototypes.

“We test the living daylights out of the cars,” Fairfield says. “We’re building a body of evidence to show that the cars are safe both to ourselves and to everybody else.”

What the future holds

Will self-driving cars take away the thrill of first learning how to drive and break the coming-of-age tradition? Some believe they will, but perhaps the tradition is fading away. In a nationwide study, Brandon Schoettle and Michael Sivak at the University of Michigan Transportation Research Institute found that from 1983 to 2014, the percentage of 17-year-olds with their license went down from 69 to 45 percent, and the percentage of 16-year-olds with their license went from 46 to 24 percent.

Fairfield feels that the development of Google’s self-driving car technology accompanies this trend of decreased teen interest in learning to drive.

“Studies say people aren’t as interested in learning to drive,” Fairfield says. “I think this [tech] will dovetail with that trend.”

“I got my license mostly for the independence.”

—junior Nandini Relan

The freedom that cars grant adolescents will always exist, but self-driving cars can change and re-define the meaning of that freedom, Fairfield says. Relan fells the same way.

“I got my license mostly for the independence,” Relan says. “I don’t want to depend on my parents or my brother for a ride anywhere. It’s not fun for them, and it takes time out of their day.”

Ultimately, maintaining the safety of everyone on or near the road, as well as freedom of movement are the two main goals of the self-driving car project, according to Fairfield.

“It [driving] is freedom. It is the ability to go where you want to go and that is a huge deal,” Fairfield says. “There still will be crazy things that happen out there on the road, but we [self-driving cars] can reduce how often they occur.”