AT T-MINUS 58 MINUTES, the robot still doesn’t have arms — among many other things. It looks like a metal doorframe, albeit one that’s only five feet tall, attached to a rectangular base with wheels and tubing curling up into the air.

T-minus 49 minutes: Two students zip tie a metal canister full of compressed air to the base, while another three attach the robot’s arm plate to its upper frame.

T-minus 31 minutes: Everyone steps back from the robot, named Freyja (pronounced Fray-yuh) by the programmers. The arms are attached, along with the pneumatic air system that will give them movement.

“Enabling!” a programmer yells from their workstation. “The Final Countdown” blasts over the sound system of room 707, and students sing along with the trumpets as they watch the arm panel, hissing with pressurized air, slowly inch up the door frame. On its way down, the panel pauses.

“Something’s wrong.” The phrase is said once, then twice, until it fills the space around the frozen robot.

“Disable! Disable!” calls senior Dhruv Lal from on his knees, waiting for the highpitched humming to die before he reaches for the tubing.

T-minus 27 minutes: Freyja has limbs and air. Both are tentatively working. As the robot rolls toward the plastic tote box on the carpeted mock field, the team watches with breathless anticipation. One team member has her hands clasped in prayer. If the arms aren’t able to lift the tote, the team has less than half an hour to fix whatever’s wrong.

The robot jerks forward to hug the tote with its arms. The tote slides out of its grasp.

Undeterred, the bot turns to follow, arms closing in on its prey, and up, up, up, hands fly up into the air, the tote is lifted, and around the room, the entire team is yelling.

The robot has four wheels, two arms and one can of pressurized air, along with a host of hidden parts. Freyja is alive and lifting.

FIRST: For Inspiration and Recognition of Science and Technology

The Palo Alto High School robotics program, in its recent years, has not placed very highly in the competitions it goes to. Yet the robotics team relies less on adult mentors than other programs, and instead emphasizes student leadership. With five captains leading different teams, two specialized managers and a treasurer, Team 8 is a well-oiled, student-run machine.

Paly’s Team 8 is one of thousands that participate in a high school robotics competition hosted by FIRST, a non profit organization. Each year, on the first Saturday of January, FIRST releases a kickoff video announcing the task that this year’s robots will have to perform in the competitions.

From that day on, competing teams have exactly six weeks, known as build season, to design and construct a robot that meets the competition’s requirements. This year, robots must lift and stack plastic crates, or totes, on top of one another. After winning one of more than 100 regional competitions spread across the country, teams can advance to the world championships.

I set out to follow the trials and tribulations of Team 8, and began my investigation by speaking with the man behind it all. That is, the guy who literally works behind the robotics lab.

Meet Chris Kuszmaul

Head Coach Christopher Kuszmaul regards me from the depths of his cushy armchair, one khaki-clad leg hiked up so that his calf is resting against the armrest. We are in his office, located adjacent to the team’s workspace, and I can’t stop staring at the bright, leprechaun green plaid pattern of his shirt. Three feet away from his head sits a bookshelf holding up three cans of Campbell’s finest and a white plastic bag with a change of clothes.

If legend can be believed, his predecessor lived in this office, Kuszmaul explains as he shows me the neglected laundry machine and hangers hidden in a glorified, oversized closet attached to the room. Kuszmaul, on the other hand, stocks his office for late nights and late nights only. If he is not enjoying his canned chunky beef with vegetables in his office, I know that I will find him hovering over the shoulders of his students, observing, commenting, supporting their actions, but almost never touching the robot or tools himself.

“If I were ‘hands-on’ year after year, then I would become a very talented robot maker,” he explains, reclining on his enormous armchair. “But that’s not my goal. My goal is to make it so my students become the best possible members of their community with an orientation towards engineering and science. And that means that any given year, I’m probably gonna be hands-off in order to give them the best opportunity to learn.”

Meet Team 8

Walk out the door of Kuszmaul’s office and you’ll find yourself in the Java Shop, a computer lab filled with bulky PCs.

The walls are streaked with cables, and a ceiling with missing panels reveals the shiny, aluminum-foil-esque piping running above students’ heads. During the school day, Kuszmaul uses this room to teach computer science. But every Thursday after advisory, the Java Shop becomes the crowded gathering place of the robotics team.

On one such afternoon, a single clap cuts through idle chatter, echoing with resounding authority. Its source is sophomore Joey Kellison-Linn, who marches down the length of the Java Shop, repeatedly smashing his hands together. The rest of the team slowly joins in, some eagerly, some with resigned amusement.

Kellison-Linn, a Team 8 programmer, inherited his position as “clapper” from his older brother, who graduated last year. He begins each meeting by clapping and waiting for everyone else to join in.

“I’m not very good [at it],” KellisonLinn admits ruefully. “I have small hands.”

Team Captain Christopher Hinstorff meanders down the center aisle under the attentive gaze of 30-something people, his pale, freckled skin glowing in the fluorescent lighting.

“What’s happening today?” he asks the room contemplatively. After a brief pause, he pivots towards junior Claire Kokontis and says, with the feigned pensive look of somebody who already knows the answer to their question, “What’s happening in build today?”

Kokontis, captain of the build team, accepts the proffered microphone with a huge smile on her face, holding it about six inches away from her chin while she talks.

After updating the team on the build goals for the day, she hands the microphone back to Hinstorff, who says with no small amount of cheer, “Thank you Claire!” and claps once. Everyone else, in a stunning display of teamwork, claps in perfect sync with him. After every captain and manager gives an update, I learn, it is customary to thank them with a “superclap.”

As the meeting concludes, Hinstorff lingers in the center aisle, arms crossed as he watches everyone disperse. Hinstorff ’s role in the program is more administrative than one might think.

As captain of the robotics team, Hinstorff is basically the captain of the other student captains, as well as of everyone else on the team.

“[My job is] to lead the team and additionally to lead the leadership, to help them be able to be more effective than they otherwise would be,” Hinstorff says. Like Kuszmaul, he tries to maintain a “hands off ” approach when it comes to building the robot.

“I don’t want to be doing our build captain’s job,” he explains. “She’s definitely capable of leading that effort without too much butting in from above her.”

The Build Captain in Action

Hinstorff is speaking about Claire Kokontis, of course, whose influence over the robot seems so great that I decide to visit her at the lab in room 903 one afternoon.

That day marks the end of Week One of build season. We are in the hub of build activity, and team members scurry around the room, testing various prototypes. When she isn’t giving advice to inquiring students, Kokontis is immersed in a forum on the FIRST website, reading about other teams’ progress in their quest to move totes

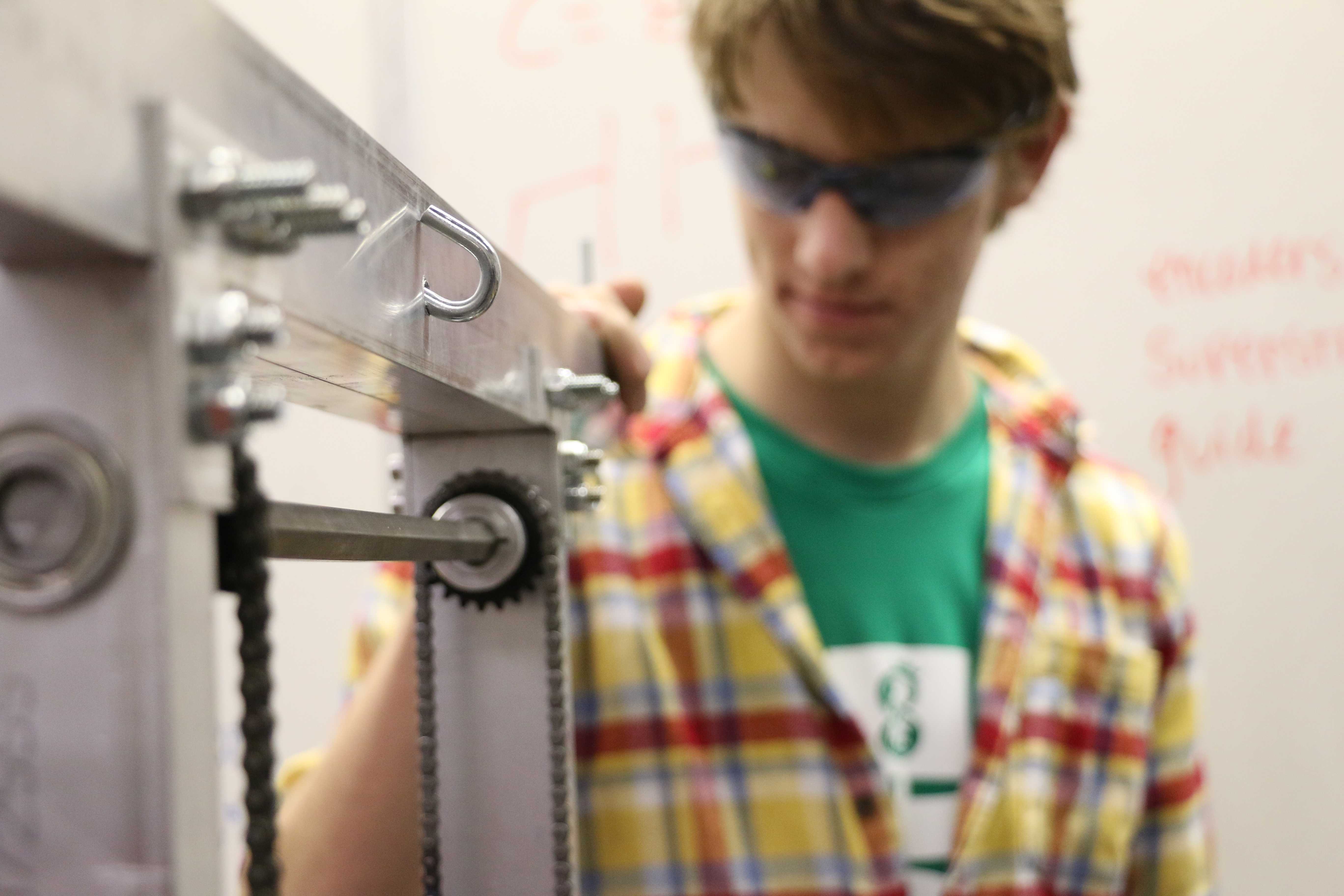

In the far corner, menacingly fenced off, an area called the Cage takes up a good third of the lab. Inside is the heavy machinery used to make robot parts: the bandsaw, the mill, the welding station and other hulking appliances that, to the untrained eye, look like nothing more than futuristic washing machines with deadly extensions.

To enter the Cage, I’m told, my hair must be tied back, and I need to wear eye protection.

I look around, and notice that almost every student in the lab has a pair of safety glasses on their person — whether it’s sitting on top of their head like a pair of sunglasses, or dangling from a shirt collar — to the point where it seems like Team 8 is making a silent, yet effective, fashion statement. Kokontis herself has “like, seven” pairs of safety glasses. She finds them lying around the lab and adds them to her own collection.

I have never seen Kokontis in the labwithout a pair of safety glasses on her face. Nor, I reflect, have I ever seen her without a smile on her face, except for one night in particular.

That One Night In Particular

We are four weeks into build season when Team 8 is suddenly confronted by their first major deadline: a leadership deci – sion to complete the robot two weeks early, so that the remaining time can be spent testing and fine-tuning the programming. If the build and programming teams don’t finish Freyja by midnight, they risk falling behind schedule.

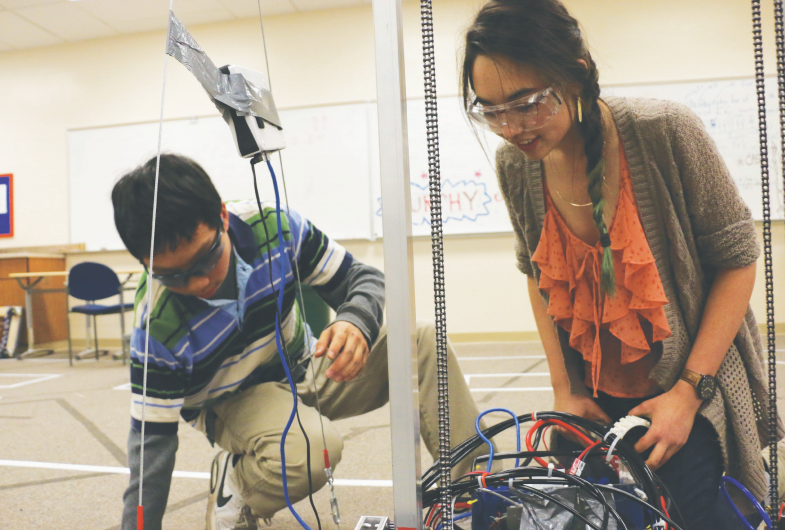

At 10:53 p.m., the robot’s entire upper structure — the elevator tower and its arms — is conspicuously absent. The beginnings of a pneumatics system gleam gold and silver within the cradle of the drive train; bright blue tubing snakes around the intri – cate engineering, searching for a connec – tion that isn’t there.

With around an hour left before their self-imposed deadline, little more than 10 students, including Hinstorff and Kokon – tis, remain to make the final push. At least five are clustered around the half-finished robot, belting along to the fast part of “Bo – hemian Rhapsody,” which blares from the lab speakers. Kokontis delivers tools and parts to the team members, bouncing with nervous energy as she dashes back and forth between the Cage and the robot.

“Everything always seems so much more simple when you’re just like, ‘Okay we have this to do, this to do, this to do,’” Kokontis reflects, counting on her fingers.

Earlier, around 10 p.m., Kokontis and lab manager junior Kenny Cheung realized that the parts of the backplate with the ro – bot’s arms did not fit together, and could not be attached to the robot. Without the arms, the robot wouldn’t be able to stack totes — the only way to earn points during this year’s FIRST competitions.

In an attempt to get the parts to fit, Cheung began drilling holes into the back – plate by hand, an act that is inexact and prone to human error. Usually, holes are drilled by machines following a ComputerAided Design (CAD), a blueprint for the robot that is created by students. In the case of the mismatched backplate, the CAD had contained an unseen flaw.

Now, at 11:16 p.m., “Living on a Prayer” pumps through the lab, with three Team 8 members leading the vocals.

“WE’VE GOTTA HOLD ON,” they scream, “TO WHAT WE’VE GOT. IT DOESN’T MAKE A DIFFERENCE IF WE MAKE IT OR NOT.”

“WE’VE GOT EACH OTHER, AND THAT’S ENOUGH FOR LOVE.”

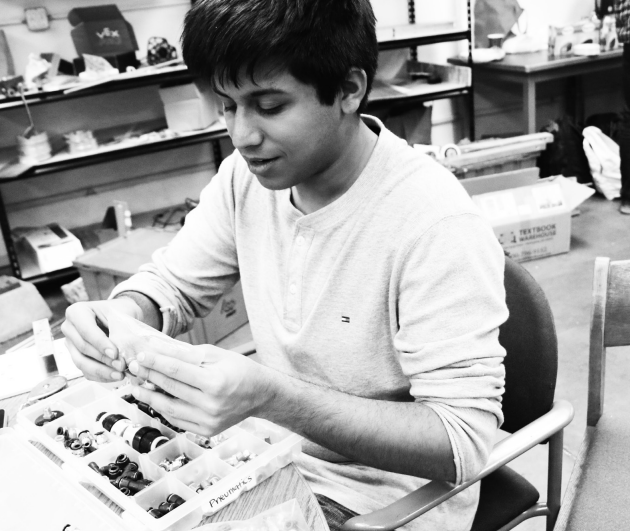

As the night progresses, the cluster gets increasingly tighter around the robot. In addition to the faulty backplate, the encoders, which collect data from the motor, were installed facing the wrong direction, and four students are working on flipping the tiny, delicate chips around.

“It was hard,” Kokontis tells me. “This deadline was set weeks in advance, and it was a thing like, ‘We are going to get this done … It’s gonna happen.’”

But it doesn’t happen.

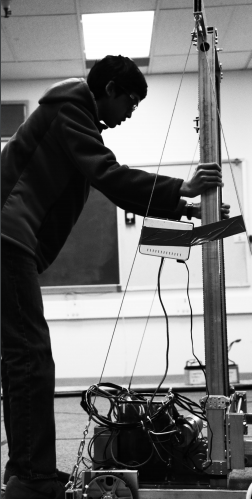

When midnight finally comes, junior Osamu Yasui is holding the elevator tower upright as the rest of the students frantically try to tighten the wires so the frame can stand on its own. A cheery song from “Singin’ in the Rain” fills the room. “Good morning!” Gene Kelly sings

As we clean up the lab, the elevator tower rests flat on the floor, five feet away from the incomplete robot. Kokontis’ shoulders are slumped, and her safety glasses — for the first time all night — have been pushed to rest on top of her head. The deadline has come and gone, and now the team is behind schedule. There will be less time to test and practice with the robot.

“You just — you push through,” she says to me, weeks after the end of build season. “That’s something I’ve definitely experienced time and time again. You just keep going no matter how difficult it gets.” She smiles a little, and adds, “So that made two weeks later even better.”

Two weeks later

Standing in the doorway of an abandoned math classroom, Kokontis clasps her hands to her chest in prayer to the gods of robotics. After two weeks of modifying and rebuilding parts of the robot, the team is facing their last deadline.

It is Feb. 17, the last day of Week Six, and by midnight, Freyja — in whatever state it’s in — must be bagged and tagged with Team 8’s identification number.

The time is 11:33 p.m., and Freyja’s backplate, completely remade from a redesigned CAD, has just been attached to the robot, giving it arms. The pneumatics system has been fixed and connected to the arms through the backplate, and both are tentatively working.

Freyja hums as it begins to turn in circles — driver Dhruv Lal is warming up on the joysticks. Five feet away, a single grey tote box sits on the floor, waiting to be picked up. Freyja makes a beeline towards it, and encloses the tote within its arms, but as they close in, the tote slides and turns away. Freyja continues moving forward and w

ithout any hesitation, traps the tote as it spins. The entire room, filled with exhausted students and mentors, cheers. Kokontis jumps up and down on her toes and screams. She looks like she might cry of excitement.

“Upsy daisy!” Lal bellows from behind the joysticks as he commands the backplate to rise along the elevator tower, bringing the arms and its prize up so that Freyja can trundle past Hinstorff and Cheung towards a platform. As Freyja drops the tote onto the platform, the room erupts in another round of applause.

Freyja will go on to stack totes atop each other, just as it will in the regional competition at Madera. Team 8 will end up placing 38th out of the 49 teams that show up, but their business plan, submitted by PR team captain Lauren Nolen, will win them the Entrepreneurship Award, an accomplishment that according to the FIRST website, “celebrates the entrepreneurial spirit by recognizing a team that has developed the framework … to scope, manage, and achieve team objectives.”

“We will make decisions from time to time, that will make it so that we will not be the world’s best, or even in the top elite group of teams,” Kuszmaul says, about the level of student leadership and mentor involvement on the team. “But before Madera, I don’t think the team fully realized that in any area that we choose as a community, this team can be the best in the world.”

For now, it looks like Team 8 has chosen to focus on student leadership and independence. The Paly robotics team hasn’t done very well in its recent competitions. But that depends on your definition of success.

“So I guess the question is, what is it that we’re talking about in terms of achievement and progress?” Kuszmaul asks me. “In terms of what you see on the [competition] field, that’s one measure. In terms of what you see, the real product, walking across the graduation stage, we kick butt. And that’s the product I’m interested in.” V