Upon first glance, the impressive building seems like a prestigious university or an upscale hotel. The majority of the building’s exterior is made up of sleek, curved glass windows, giving the building an exceedingly modern aesthetic, and an American flag rests near the entrance. This aesthetic continues upon entering the building. A comfortable lobby rests behind the doors, and colorful designs line the walls. Little details seem off, such as the protective glass window behind which the receptionist stands, but the illusion is only shattered when Correctional Officer Patrick Lucy walks out from a locked door in full police uniform and welcomes us to the Maple Street Correctional Center. This newly-constructed correctional facility, at 1300 Maple Street, Redwood City, was built with the motto “correction with care.” It is the pinnacle of prison reform, with rehabilitative programs in spades. However, not all prisons are created equal; private prisons, or for-profit prisons run by private organizations, are particularly controversial due to doubts about their effectiveness and quality.

Private Prisons

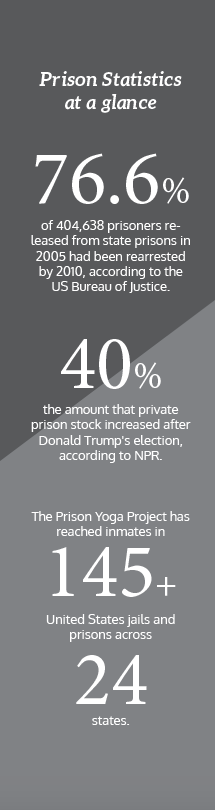

Under the Obama administration, the phasing out of private prisons was begun, and was met with much support. However, with the election of Donald Trump, private prisons could make a comeback; according to NPR, within a single week after Trump’s election, the stock values of prominent for-profit detention companies increased by up to 40 percent. “Private prisons should be shut down and closed,” Lucy says. He claims that government facilities not only have to abide by much higher standards than private prisons, but that the majority of people who work as corrections officers are motivated to serve, whereas staff at private prisons are merely seeking profit.

“Rehabilitation has just really, really gone by the wayside.”

—Larry Marshall, Stanford law professor

Story continues below advertisement

Stanford professor of law Larry Marshall agrees; because the sole motive behind private prisons is profit, he claims that they provide the fewest services possible in order to maximize their income. Additionally, because they are often in remote or desolate locations, inmates are much less accessible to their lawyers or to friends and family who may wish to visit them, and will lack a community to return to upon release. Santa Clara County District Attorney Jeff Rosen offers a different perspective on private prisons. According to Rosen, private prisons are currently incentivized to hold the largest number of inmates for the longest amount of time; however, the system could easily be altered in order to incentivize rehabilitation. Rosen claims that through a simple plan, whereby private prisons receive payments for each released prisoner who does not relapse into a life of crime — and has to pay a fine each time a released inmate does end up back in jail — a capitalistic drive to offer quality rehabilitation would exist. These private organizations, which have more resources than government-run prisons, could devise new ways to effectively rehabilitate inmates and reduce recidivism.

The problem of recidivism

Recidivism is a large problem in the criminal justice system, according to the United States Bur eau of Justice, and its reduction is one of the main goals of modern prison reform. The Bureau’s report shows that 76.6 percent of 404,638 prisoners released from state prisons in 2005 had been rearrested by 2010. “Recidivism is high, it has always been very high,” says Palo Alto Police Department Sergeant DuJuan Green. “Sadly, until we’re able to create a more stable environment, you’re always gonna have recidivism.” According to Larry Marshall, a Stanford professor of law and fierce combatant of wrongful convictions, part of this problem stems from the fact that the focus of the prison system has shifted over the years from rehabilitation to retribution. “Rehabilitation has just really, really gone by the wayside.” Marshall claims that this was a byproduct of the politicization of the crime issue, which began when Richard Nixon ran on an anti-crime platform. Consequent politicians, such as Bill Clinton, would later follow suit, demonstrating their toughness and strength of character through crackdowns on crime. According to Defense Attorney Jeffrey Hayden, during the past 10 to 15 years the drive of politicians to be tough on crime has substantially decreased, and an increasing number of reform bills have been passed. Most recently, Proposition 57 (or the Public Safety and Rehabilitation Act of 2016) passed, the primary purpose being to increase the availability of parole options. This followed a chain of other propositions, including props 36 and 47, which were vital in reducing punishments for minor crimes and first-time offenders. Prop 47 reverted many felonies to misdemeanors; according to Hayden, this was a huge help for many, as offenders were able to appeal to have their past felonies retroactively changed to misdemeanors. Not only would this reduce sentence times for current inmates, but the alteration to prior inmates’ records allow them to more easily gain professional licenses and jobs.

Recidivism is a large problem in the criminal justice system, according to the United States Bur eau of Justice, and its reduction is one of the main goals of modern prison reform. The Bureau’s report shows that 76.6 percent of 404,638 prisoners released from state prisons in 2005 had been rearrested by 2010. “Recidivism is high, it has always been very high,” says Palo Alto Police Department Sergeant DuJuan Green. “Sadly, until we’re able to create a more stable environment, you’re always gonna have recidivism.” According to Larry Marshall, a Stanford professor of law and fierce combatant of wrongful convictions, part of this problem stems from the fact that the focus of the prison system has shifted over the years from rehabilitation to retribution. “Rehabilitation has just really, really gone by the wayside.” Marshall claims that this was a byproduct of the politicization of the crime issue, which began when Richard Nixon ran on an anti-crime platform. Consequent politicians, such as Bill Clinton, would later follow suit, demonstrating their toughness and strength of character through crackdowns on crime. According to Defense Attorney Jeffrey Hayden, during the past 10 to 15 years the drive of politicians to be tough on crime has substantially decreased, and an increasing number of reform bills have been passed. Most recently, Proposition 57 (or the Public Safety and Rehabilitation Act of 2016) passed, the primary purpose being to increase the availability of parole options. This followed a chain of other propositions, including props 36 and 47, which were vital in reducing punishments for minor crimes and first-time offenders. Prop 47 reverted many felonies to misdemeanors; according to Hayden, this was a huge help for many, as offenders were able to appeal to have their past felonies retroactively changed to misdemeanors. Not only would this reduce sentence times for current inmates, but the alteration to prior inmates’ records allow them to more easily gain professional licenses and jobs.

Rehabilitative programs in prison

One particularly potent form of prison rehabilitation comes in the form of education. According to California’s Office of Correctional Education, many programs, such as the High School Diploma Program, exist to prepare inmates for life on the outside. Additionally, career-oriented classes such as Construction Technology, Carpentry and Auto Mechanics, are common, which the OCE claims reduce recidivism by allowing rehabilitated inmates to earn living wages upon release. Lucy says that correctional officers are integral to rehabilitation as they offer guidance to inmates. “I’m like a parent in a way,” Lucy says, describing his relationship with prisoners.

“There’s entire generations that are growing up expecting to spend time [in prison.]”

—Jane Mitchell, CEO of the Reset Foundation

The aforementioned Maple Street Correctional Facility, where Lucy works, offers many programs to prisoners who choose to turn their lives around. “They [inmates] get to learn how to have a career, and from there they can get jobs where they can hopefully never come back here,” Lucy says. However, Lucy makes it clear that the inmates themselves must make the commitment to rehabilitation in order to truly benefit from the available programs. Unfortunately, not all prisons are as rehabilitation-oriented as the Maple Street Correctional Facility. However, according to Lucy, many programs — such as Narcotics Anonymous, Alcoholics Anonymous and personality and job training courses — are very common among prisons nationwide.

Progressive alternatives

Jane Mitchell, founder of The Reset Foundation, claims that traditional prison programs are insufficient. This belief inspired the creation of her foundation, an organization whose core goal is to “help people break out of that cycle” of prison to poverty and then back to prison again. “There’s entire generations that are growing up expecting to spend time in prison,” Mitchell says. “I used to teach in jail, and in one of my classes I had a guy who met his father for the first time [in prison].” In cases such as these, where people expect to be incarcerated for significant portions of their lives due to their socioeconomic status or family history, Mitchell expresses doubt that in-prison programs are enough to end to the problem. To remedy this situation, Mitchell is working on expanding the “network of campuses that serve young people who otherwise would be sent to prison.” The people selected by the foundation, who typically face sentences of up to ten years in prison, instead (with court approval) attend one of the foundation’s residential campuses, where they live rent-free and gain an education over two years. After those two years, participants are free to go back to their lives without having set foot in prison, and are far less likely to end up back on trial.

Reform going forward

Donald Trump’s election has the potential to alter the progress of prison reform; however, according to Hayden, because the vast majority of cases are prosecuted in state and local court systems as opposed to federal, major effects may not be felt. “California is clearly going in different directions than the nation voted in the last presidential election,” Hayden says. However, he does think federal meddling is possible: “At what point does the federal government start prosecuting things because they disagree with the way states are running things?” Hayden also speculates that the federal government could resort to holding funds from California’s prison system. As of now, however, the Trump administration has made no such strides, and based on the way the prison system has been moving in recent years it seems likely that California prisons will continue to institute reforms which further reduce overpopulation and recidivism. “A true conservative would acquiesce to the state, but who knows,” he says.

On a mission to spread yoga to people other than wealthy white women, James Fox began teaching classes at California’s San Quentin prison in 2002. “Based on my experience of teaching there I began developing a methodology and a curriculum [for teaching yoga].” Fox says. Fox published this curriculum in a book that he began sending out to prisoners for free in 2010. Thus came the birth of Fox’s non-profit, the Prison Yoga Project, which has now affected inmates in more than 145 penitentiaries in 24 states. The mission of his organization is to establish the practice of yoga and mindfulness in prisons as a method of rehabilitation. Fox, who has practiced yoga for many years, found meaning in spreading yoga to others — specifically prisoners. “I knew I didn’t want to work in a yoga studio,” Fox says. “My primary motivation was to bring yoga to populations that weren’t being exposed to it.” According to Fox, the Prison Yoga Project has caught the attention of prison employees in many countries around the world, including Sweden, Norway and Germany. Fox has travelled to these countries to teach yoga and mindfulness to prisoners abroad — as well as teachers in foreign prisons who have then replicated his lessons, extending the organization’s reach. In fact, Fox’s book has recently been translated into Spanish, preceding the official launch of the Prison Yoga Project in Mexican prisons this month. Fox feels that the effectiveness of yoga in prisons comes from an emphasis on one’s sense of self. “The real DNA of a yoga practice is all about increasing self-awareness [and] self reflection,” Fox says. “Increasing self-awareness is the beginning of behavioral change.” Ultimately, Fox believes that his organization’s work reaches far beyond the lives of inmates during their sentences. “If you’re providing programs for them [prisoners] while they’re in [prison], you’re helping to impact the recidivism rate,” Fox says. “You’re helping to provide life skills, education [and] lasting behavioral changes that are going to carry over once they’re out.”