“The college I go to will determine the rest of my life. If I don’t get into my dream school, then I am a failure and will die alone.” This is a common thought sequence in the high-strung and overachieving environment that is the Palo Alto public school system.

While I may criticize the culture that surrounds our education system, I do acknowledge the fact that we high schoolers in Palo Alto receive a world class education that gives us a leg up when applying to college. However, this is not the only advantage that we share. A good portion of us, myself included, have possibly the greatest advantage of all — we are part of the American bourgeois and can afford to be sent to any college that our little hearts desire.

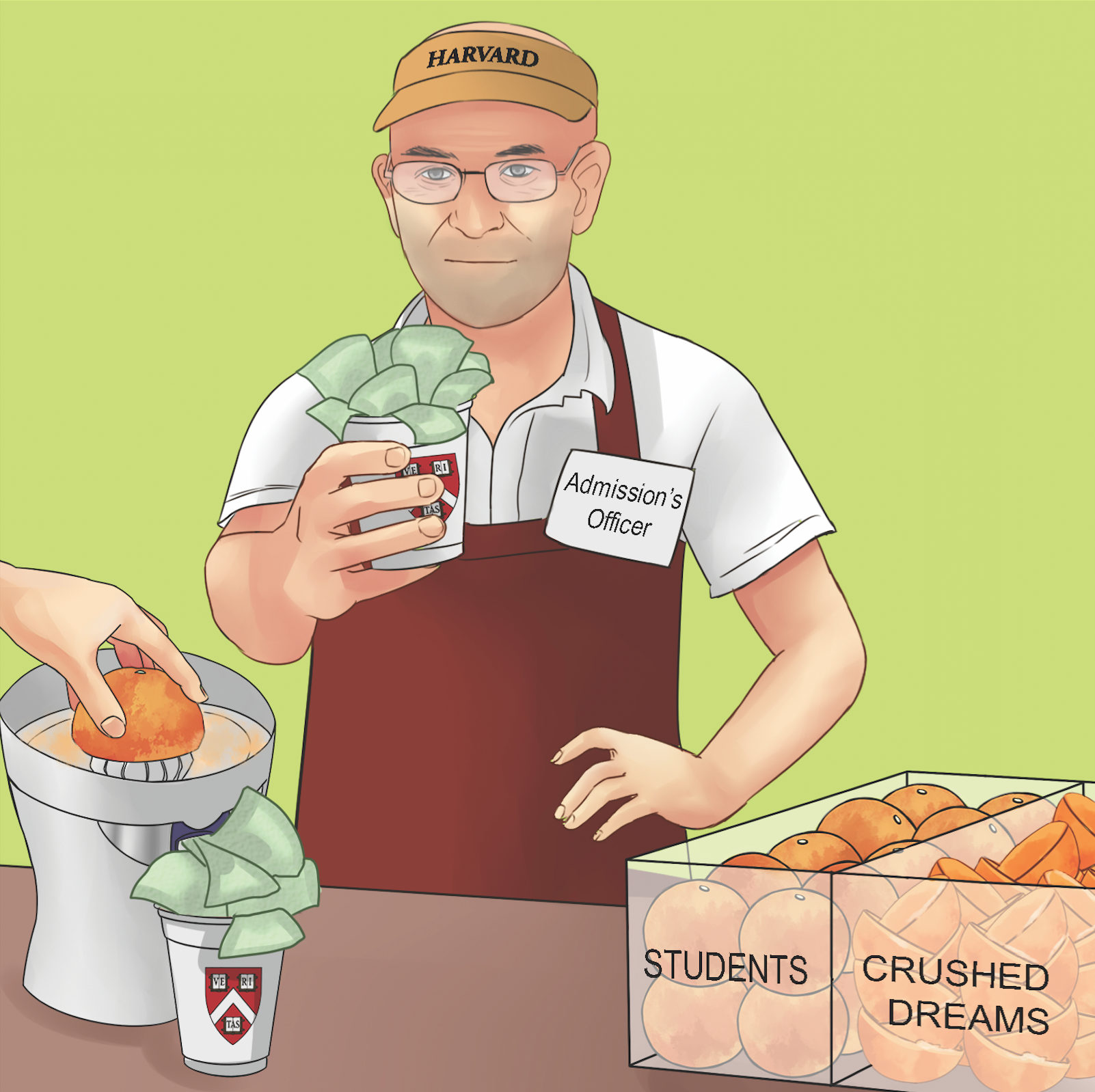

Many students do not share this luxury, and the problem of rising college tuition prices maintains the long-held tradition that selective universities — this is not referring to the selectiveness of the schools, but rather a black-and-white distinction between whether colleges admit everyone or not — will largely only enroll the affluent.

The current rise in tuition prices began in the ‘80s and has continued for more than three decades, according to labor economist Professor Ronald Ehrenberg in his paper Tuition Rising: Why College Costs So Much. Recent years have seen a ballooning in costs, with a 78 percent increase in tuition prices between 1987 and 2010, according to economists Grey Gordon and Aaron Hedlund.

The upsurge in tuition is grotesque — it is one of many manifestations of the archaic tradition surrounding the privilege of the prosperous that still abounds in our society. This dangerous growth is tightly squeezing the budgets of the American middle and lower class families.

The constant supply of applicants has allowed institutions to raise their rates while remaining assured that there will still be plenty of high school graduates eager to take on student loans so they can put a prestigious university on their résume.

These new funds are placed back into the system where they go to improving the university and making the school more appealing. This trend draws in more potential applicants and thus makes it easier to raise tuition rates.

“The objective of selective academic institutions is to be the best they can in every aspect of their activities,” Ehrenberg states. “They aggressively seek out all possible resources and put them to use funding things they think will make them better. To look better than their competitors, the institutions wind up in an arms race of spending.”

An “arms race of spending” is not what our education system needs. Equal opportunity is an American value. If we fail to provide even a modicum of fairness in this system, then can we really be proud of our world class universities?

But we do not have to consign ourselves to this iniquitous system. Government regulation of tuition price increases could help keep college affordable for all. There are a few initiatives that colleges have taken to help make their education available to those who cannot afford it, one example being Stanford University’s recent promise to give a free education to all who are accepted whose families makes less than $125,000 a year. We cannot, however, rely on colleges to take action on their own. Without regulation, this detrimental trend will continue and the American dream will once again become unachievable for the middle and lower classes.