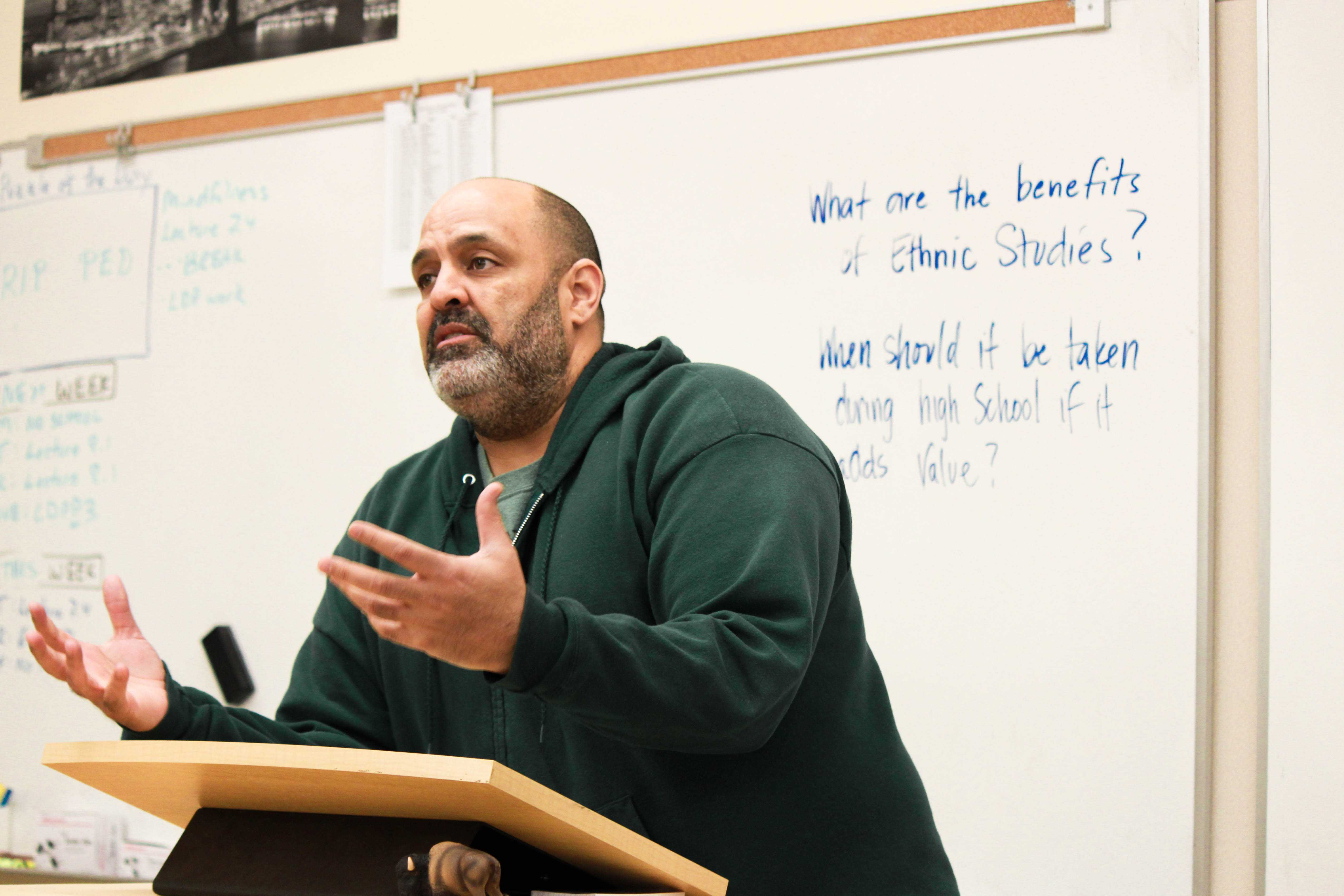

Social Studies teacher Justin Cronin’s baritone voice bounces off the walls, filling the spacious classroom as he strides to the front of the class. In his hands he holds an unassuming news article — a single sheet of paper with black text marching down both sides. When the rustle and murmur of his students fade away, he clears his throat and begins to tell the story of two students not much older than the ones who sit before him.

One from Stanford University, the other from Vanderbilt University. One a swimmer, one a football player. Both accused of multiple counts of sexual assault. One sentenced to six months in a county jail, the other sentenced to 15 to 25 years in prison. Both crimes are reprehensible, but only one was treated as such. One student is white, one student is black. Can you guess which is which?

It is easy for students to match the punishment to the athlete — they are all too familiar with inequalities that continue to plague our nation.

With this story fresh in their minds, the students in Cronin’s class begin another period of Ethnic Studies, a social science elective running for the first time in 10 years at Palo Alto High School. The discussion-based class delves into topics of race rarely discussed in core history classes and focuses on instilling empathy and awareness in students as they prepare to leave the bubble of the community.

The revival

For a decade, too few students enrolled in Ethnic Studies for the class to run. However, a peak in students’ interest led to the formation of a single Ethnic Studies class in second semester this year.

“I think that the current climate plays into the willingness of students to have maintained their sign-up,” Cronin says. “But also schedule-wise the stars sort of aligned for it to happen.”

Despite only having enough students to fill one semester, a little bit of luck with teacher schedules and the persuasion of guidance counselors helped revive the elective.

“Mr. [Charles] Taylor, in Guidance, helped channel some kids into doing this and that’s where the [political] climate comes in — the willingness to keep it on their schedule as opposed to doing something else,” Cronin says.

When current Palo Alto administrator Katya Villalobos taught the class for a semester in the spring of 2000, students explored the history of different ethnic groups in California, as well as the depiction and outside perceptions of those groups. Similarly to the Ethnic Studies class running this semester, the class was discussion-based and involved more reflection than typically found in history classes.

“I think for you to understand where we came from and where we’re going, it’s important for you to understand who came, and who is coming,” Villalobos says. “That’s why we need a class like Ethnic Studies.”

Connecting personal with political

“I’ve had experiences of being somebody of color and what that entails with being stopped by police in my car, or disappointing looks of girlfriends’ parents,” Cronin says. “That’s the thing with being of color — it’s like you don’t really have the option of putting it down … it’s like it’s always there, regardless of where you are [or] who you’re with.”

By bringing his own personal experiences to the class, Cronin hopes to broach the sensitive subject of race, bringing to life the inequalites minorities face everyday.

“Outside of this class, there’s a lot of problems with talking about race and people don’t want to say anything,” says senior Jazmine Johnson Jackson. “Now we have a class where we can just discuss … the problems about race and how you feel about it.”

Students are taught to be color brave as opposed to being color blind and to recognize that each culture is unique.

“Color brave is based on the idea of not being color blind … when people say they don’t see color it actually detracts from the conversation because then what you’re not seeing is the struggle or inequality,” Cronin says.

As racial tensions rise in the United States and our own government battles allegations of racial discrimination in immigration policy, policing and incarceration, students believe that the discussions occurring in Ethnic Studies are promoting conversations that should have happened earlier.

“It’s so easy to get caught up in your own social circle and not really have a better understanding,” says senior Julianna Roth. “We [are] in such a bubble, people need to have that opportunity to gain that knowledge before they go into the real world so they don’t offend someone else.”

Senior Paul Jackson III seconds Roth, explaining that he signed up for the class to get different perspectives from people of different ethnicities.

“That’s important especially right now as we’re growing up and ready to step out into the world for ourselves,” Paul Jackson says.

Living in a liberal community such as the Bay Area and having had a more left-leaning government in recent years has left many feeling removed from the racial prejudices that continue to fester within society.

“Because we had a black president, I think a lot of people were like ‘oh, racism is over, there’s no reason to talk about it because it’s over,’” says senior Naima Castaneda-Isaac. “But we see that that’s clearly not true, and I think with the recent election, people are seeing the true faces of America.”

“Because we had a black president … a lot of people were like ‘oh, racism is over … but we see that that’s clearly not true.” — Naima Castaneda-Isaac, senior

Cronin makes sure to highlight tolerance and acceptance of varying opinions, a lesson that many students have come to value.

“I think that’s something that our country is really missing right now,” Castaneda-Isaac says. “If we had the ability to empathize with one another, and actually talk about issues, I feel like some of [those] issues would dissipate.”

By teaching students to embrace tough conversations and arming them with information from multiple viewpoints, Cronin aims to shift student focus to similarities as opposed to differences.

Implementation and resistance

In 2016, California Gov. Jerry Brown signed legislation requiring the state’s Instructional Quality Commission, responsible for developing and recommending curriculum, to develop a model ethnic studies curriculum for high schools. First suggested in 2002, the legislation finally passed two years ago thanks to California Assemblyman Luis Alejo from Salinas. The curriculum for the class is expected to be completed around June 2019 and will be adopted at the end of that year, according to Alejo’s office.

“One of the major ideas behind Ethnic Studies is this idea of something that is culturally relevant to the students being served … [but] that’s not to say that there aren’t general principles in play,” says Thomas Dee, Stanford University professor and Director of the Stanford Center for Education Policy Analysis.

Dee, who co-authored “The Causal Effects of Cultural Relevance: Evidence from an Ethnic Studies Curriculum,” hopes that the model ethnic studies curriculum will allow schools to modify content to accommodate differences in school culture.

The rising popularity of ethnic studies classes was accompanied with backlash. The state of Arizona banned a Mexican-American studies curriculum in Tucson public schools in 2011, with many government officials claiming the curriculum was too divisive.

“Individuals saw it as very anti-white, and that’s not the message,” Cronin says. “I’ve said it in class: It’s not an ‘I-hate-white-people’ class. That’s not the point of it.”

Rather, the focus of ethnic studies classes is to shed light on the stories of minority groups often ignored by Eurocentric history curricula.

“This is the big tension with Ethnic Studies. We’ve got this notion of diversity in the U.S. that is ‘e pluribus unum’, out of many one … they keep their distinctiveness but complement each other,” Dee says. “My hope is that evidence like ours can reframe the debate toward whether and why these kind of curriculum appear to have a very special power.”

Digging deeper

In his paper, Dee investigates the impact of ethnic studies courses on students at risk for dropping out of school, using five years worth of data gathered from several San Francisco high schools.

Dee and co-author Emily Penner found that students who enrolled in the class demonstrated an improvement in their grade point average and attendance records, which may be attributed to a cultural alignment present in the course that is rarely found in other courses.

“[It is] very important for students, to help unlock their potential, for them to see their own out-of-school experiences represented in the lenses that are brought to the kind of history they’re learning,” Dee says. “Classrooms are highly evaluative settings where if you belong to some racial or demographic subgroup and you think that people may hold stereotypes about your belongingness, it creates a kind of self-fulfilling anxiety about your capacity to perform in these settings.”

According to Dee, the implementation of an Ethnic Studies course in high schools would forewarn students about stereotypes and give them an opportunity to affirm their core values in a classroom setting, which would promote students’ growth mindset.

Ethnic Studies 3.0

If Cronin has the opportunity to teach Ethnic Studies again, he plans to continue with the central theme of identity and the discussion-based format, but alter the curriculum so it more closely resembles ninth grade courses taught in Southern California. He would spend less time talking about history and more time discussing current issues related to minority groups.

Cronin’s hope is that Ethnic Studies will promote conversations among students and help students learn how to take action against the issues they study in class.

“Whether you hate it or love it, it still doesn’t further the conversation, it doesn’t make everything equal,” he says. “Yeah we talk about it whether it’s right or wrong, but there’s far more deeper levels that need to be discussed in this nation before we can truly move forward.”

Ethnic Studies classes like the one at Paly play an important role in allowing all members of society to feel accepted and influential in the shaping of our nation’s rich and complex history.

“This is part of the American experience: how to live with and leverage to great effect the diversity that exists in our society,” Dee says. “Elements of that diversity and inclusion should be reflected in everyone’s curriculum.” v