When he was in the 10th grade at Gunn High School, Palo Alto High School social studies teacher Eric Bloom tried to cheat on his German vocabulary test.

“[First], because I thought I could get away with it and second, because I had forgotten and I didn’t even look at the vocab,” Bloom says. “I got thrown out of the department. There were six other people doing the same thing and I was just the one who got caught.”

If Bloom was a student last year, Paly’s administratiors would have marked the incident as his first “strike” out of three, as directed by the traditional academic honesty policy, which came to an end in 2013. Bloom would also have received a zero on his vocabulary quiz and a warning would have been sent home to his parents.

Now, Bloom’s cheating would be classified as a Category B violation, according to the school’s new 2014 policy, which would offer Bloom two choices:

In the first option — the traditional disciplinary process — Bloom would not only receive a zero on the quiz but would also be required to redo the assignment, write a reflection on his actions, attend Saturday school and meet with an administrator. His parents would be notified and he would be considered ineligible for the California Scholarship Federation or any other academic honor that Palo Alto Unified School District offers.

Or, with the second option, Bloom could embark on the new Process for Restorative Justice and circumvent the traditional consequences.

The goals of the Restorative Justice path, introduced earlier this school year, are to achieve “genuine learning that leads to a change in behavior” and to restore “the wrongs done to individuals and the community affected by the individual’s actions,” as stated in the policy’s page on the Paly website.

Although students will still be required to make up for the corners they tried to cut, the Restorative Justice path is Paly’s pioneering step towards the realm of non-punitive administrative action, according to Bloom. The new path reflects a change in the policies of other high schools as well, adding Paly as another member to the movement advocating increased communication between students and adults.

The dialogue supposedly not only benefits the student — providing a chance for them to explain their side of the story — but also aims to help teachers and administrators understand cheating culture and how to prevent future incidents of the same nature.

“We can’t punish people out of cheating,” Bloom says.

Paly AP Psychology teacher Melinda Mattes agrees that the non-punitive nature of the restorative path will help students reform their cheating habits.

“It’s not like kids don’t learn from punitive experiences — they certainly do,” Mattes says. “But research shows that you learn more how to avoid the punishment rather than learning whatever it is you’re supposed to learn.”

Mattes says she believes that at its core, the Restorative Justice process promotes growth.

“At this age, high school students are … still within the moral development phase,” Mattes says. “There’s all this stuff going on in this frontal lobe and all these connections still being made.”

The restorative path may play a role in preventing future cheating incidents by changing the culture around such behavior, Mattes says. Students who go through the Restorative Justice path may become future upstanders to other cheaters. At a time when the teenage brain is growing rapidly, Mattes says the restorative path can provide guidance for students when it comes to future decision-making and encourages them to not only choose not to cheat, but also to stand up to other cheaters and change the culture by rejecting the norm.

In addition to preventing future transgressions, the restorative path also sets out to repair the relationship between the student and teacher, using discussion as a launchboard for creating understanding and trust.

“[Teachers] want to believe the best in all students,” Mattes says. “This is a great process … where we get to see that growth coming out.”

Paly student Kevin, whose name has been changed along with other current and former Paly students quoted in this article, doesn’t believe that there will ever be complete trust on a teacher’s behalf after any cheating incident.

“I always think that even after this [new policy] happens, the teacher … is always looking out for you,” Kevin says. “You put yourself on a blacklist for teachers to keep track of.”

Bloom says that teachers themselves are responsible for taking preventative action to make cheating difficult in the classroom.

“If you have a pool at your house, you are required to build a fence around it so people don’t accidentally fall in,” Bloom says. “If someone falls in your pool and drowns, it is your fault because you didn’t build [the fence].”

CHEATING CULTURE

There exists an entire culture when it comes to academic cheating, one that isn’t acknowledged outright until the kid sitting next to you wants to copy your homework.

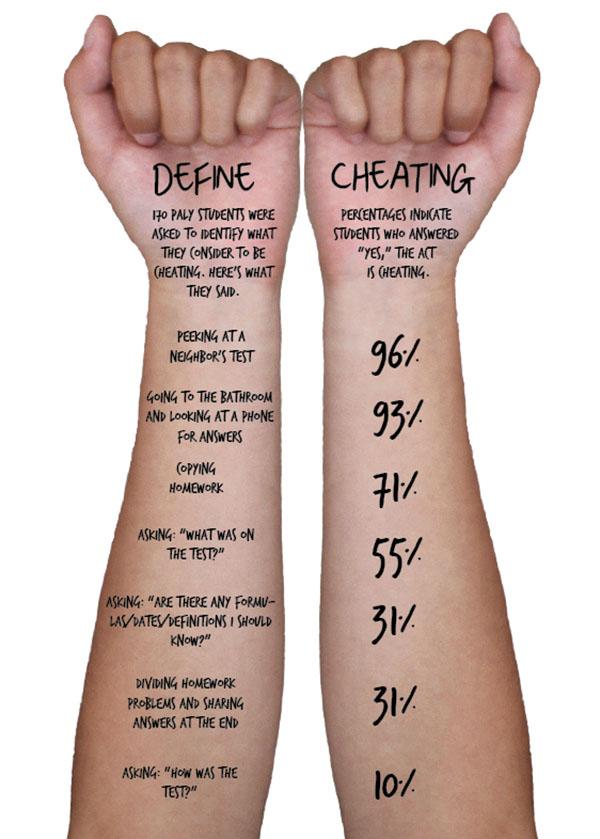

When only 44 percent of Paly students surveyed strongly agree that cheating is wrong, it becomes clear that while the Paly community may not condone cheating, it certainly does not try to stop it. In the cases of last year’s cheating scandals in the AP Psychology and Algebra 2 classes, where information about tests was leaked multiple times, the rare upstanders did not confront the cheaters directly but went to the teachers instead. The underground mob mentality protecting cheaters has the potential to thrive best at high schools in particular, where social and academic pressures can work together to influence students’ decisions.

There are two broad areas of reasoning that factor into a student’s choice to cheat in school, according to Mattes. The first, personal factors, can include how a student was raised and are therefore out of the teachers’ and administration’s control. But Mattes says the school can counter this by controlling the student’s learning environment.

“I think we can set up situations that either encourage or discourage cheating,” Mattes says. “There are things that we can do that take the pressure off of the ultimate grade and put the focus more on the learning. …What we [teachers] want are for students to learn things. But we have this system where, in order to assess your learning, we have to give you this grade.”

Kevin says he believes that Paly’s intense academic environment can lead Paly students to cheat.

“It [Paly] is a better school, a better education,” Kevin says. “I feel like students need to cheat just to keep up with those standards.”

Kevin first cheated when he whispered answers to a friend during a test.

“He was a friend, and he was struggling in the class,” Kevin says. “I felt bad for him.”

However, according to Kevin, there are some students who will cheat even though they understand the material simply because it is easier. Paly grad Cole identifies as this latter type.

“For me personally, I feel like cheating was more just a thing of laziness; a shortcut instead of studying,” Cole says.

But the underlying problem, Cole believes, is that too many people at Paly cheat for the non-cheating students to succeed.

“If you don’t [cheat], you’re disadvantaged,” Cole says.

As a freshman, Kevin came into high school believing that he would never cheat on an assignment. Throughout his time at Paly, as he saw more students copying off each other, Kevin’s view of cheating shifted based on what he perceived to be the norm both inside and outside classes.

“This whole cheating thing start[s] with pressure,” Kevin says. “Everyone does it.”

This pressure, Kevin continues, can extend to the preservation of the cheating culture through a social stigma associated with “snitching.”

“Snitching” or “ratting someone out” are terms often used to negatively refer to those who inform teachers about cheating. The information passed along does not have to include names for one to earn the title of “snitch;” just the fact that a cheating incident occurred is enough to earn scrutiny from the teacher, which inevitably leads to subsequent hostility from students.

“The reason cheating persists at Paly or at any campus is because students allow it to happen,” Bloom says. “They don’t want to rat people out.”

While the student attitude towards snitches can keep teachers unaware of cheating incidents, social implications also play a role in instigating cheating behavior among high schoolers. Unspoken agreements can lead to a symbiotic relationship that perpetuates a cycle of cheating.

“If you help someone with a test, they’ll help you with a test if you need it,” Kevin says. “They kind of return the favor.”

Failing to hold up your end of the bargain, Kevin adds, results in a sullied reputation among other cheaters. Although Kevin believes that cheating is morally wrong, he says that it can be considered a form of helping other students.

“It’s not wrong to help the people who don’t know anything; that’s a good thing,” Kevin says. “[Cheating is] just considered wrong.”

Though Paly’s Restorative Justice path does not immediately condemn students to a series of punishments, a Restorative Justice panel of students and adults will review the student’s case after discussion and decide how the student “can provide a satisfactory restoration for the harms done,” an assignment that may include punitive tasks.

“[The restorative path is] not an easy path because it requires a lot of growth and a lot of self-awareness and introspection,” Mattes says. “But that’s also what aids in that growth and getting beyond the transgression and moving forward, because that’s what [Paly is] ultimately about.”