The summer before first grade, my family and I moved from Tokyo to Palo Alto, a city I’d never heard of. As we drove up to our new home, I remember seeing a flattened, brown squirrel that had been run over by a car. Even though some might have seen this as a bad sign, six-year-old me was just excited to see a wild squirrel on the street, something I’d never seen in Japan. As I look back on this flattened squirrel, I realize moving to a different country was just like that memory: exciting.

However, on my first day of first grade, I didn’t have any homesick tears or feelings that I didn’t fit in. As a result, I was confused as to why my two older sisters came home crying.

When I lived in Tokyo, I attended the American School in Japan, or ASIJ, which made efforts to share Japanese culture with Japanese-American children living in Japan.

At ASIJ, most of my teachers were elderly white women who only spoke English during class. Most of my friends were like me, half Japanese and half white, and we all spoke English to each other. My mother, who is fluent in both Japanese and English, never made a conscious effort to talk to me in Japanese. But I don’t blame her, because my usual response to her occasional efforts to speak Japanese to me was, “Huh?”

Looking back now, it seems as though moving to a different country wasn’t a big adjustment due to how young I was when I moved here. Despite that, the seven years I spent in Japan taught me transformative lessons about my identity. Through Japanese sweet potato picking in the autumn, I discovered my hatred of getting dirty. In winter, it was while mochi pounding that I found my love for chewy rice cake, doused in salty soy sauce and wrapped in seaweed. At the end of kindergarten, I experienced sumo for the first time and learned the proper routine of a sumo wrestler.

In recent years, I have reflected on what my life would have been like if I had stayed in Japan. As I’ve explored this idea further, I have also questioned if I have done enough to maintain my mother’s culture while here in Palo Alto or what I should be doing to accomplish that.

A big reason why I question whether I connect with my culture enough is because my two older sisters are more connected to Japanese culture than me. My sisters are four and eight years older than me, meaning that they had an extra four and eight years living in Japan.

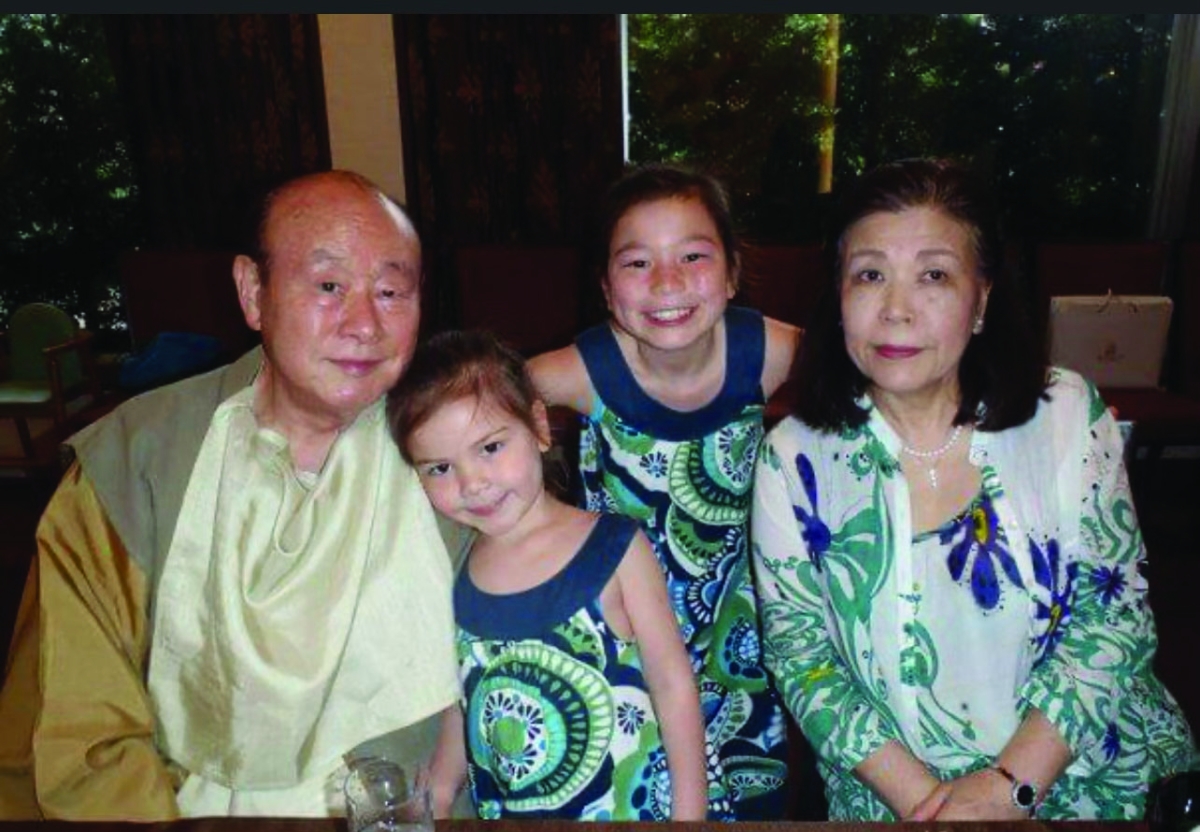

Visiting my grandparents’ house in Tokyo, my sisters can communicate easily, while I need a translator. They not only speak more Japanese than me, but I’ve also been told they look more “Asian” than me, creating this constant comparison between me and them. I feel as though I will never be as Japanese as them.

Along with my sisters, I compare myself to my younger self. The younger me was fluent in Japanese, went to Japanese daycare and could communicate with my grandparents. Why can a four-year-old me be better connected to her culture than a 17-year-old me? Not only am I comparing myself to other people, I am comparing myself to someone I once was.

As I look at my mother, I see all the things that she does to maintain her Japanese culture in America. Once a week she attends Shodo, a Japanese calligraphy class. Two times a week, she attends an Ikebana class, a Japanese flower arranging class. These efforts are dispersed throughout my home; calligraphy ink and brushes on the dining table and flowers decorate our house.

I realize this has been a process for her as well. She also feels disconnected from her family and she has to put in the effort to maintain her culture. My ability to connect with my culture will develop through my life, and putting pressure on perfecting my culture at a young age will only discourage me.

Maybe at 50 I will be fluent in Japanese and attend Shodo and Ikebana classes like my mom. Maybe I need to wait until I turn 80 to be satisfied.

But that’s okay. I have so much more life to live, and there is no way that I can keep learning about my culture if I’ve already perfected it.