On April 30, Yahoo broke the news that Google will reportedly stop selling ads using personal information about students from its Apps for Education products. Google also says that Gmails sent through Apps in Education products will notbe scanned for student interest, a previous tactic for providing consumer information for advertisers.

Google’s recent effort is only a part of the worldwide movement toward Internet privacy in response to advancing technology.

On a more local scale, the state of California enacted its new “Do Not Track” disclosure requirement law on Jan. 1, 2014. According to California’s Business and Professions Code section 22577, which includes the new policy, businesses that operate a commercial website or online service now must “conspicuously post” their privacy policies on their websites. Online services must now inform consumers of the collection of personally identifiable information, while also disclosing whether other parties may collect information about a consumer’s online activities over time and across different websites. “Personally identifiable information” includes a user’s name, social security number and any form of contact information.

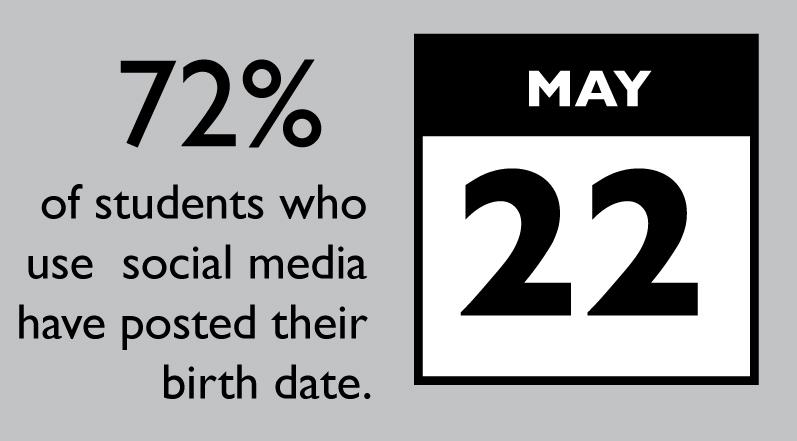

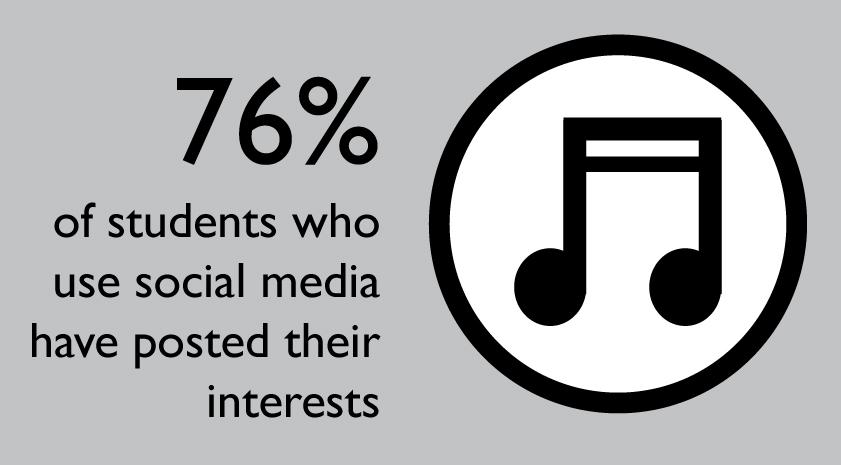

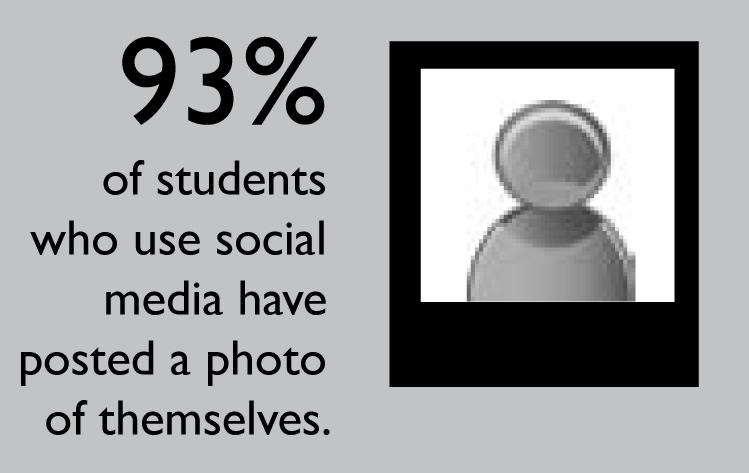

Every photo, tweet, status update, Google search and electronically purchased item also adds to users’ digital profiles. According to survey among Palo Alto High School students, 93 percent of students who use social media set their profiles to completely or partially private. However, hardly any information remains truly confidential. Technology companies, online advertisers and even the government have online consumers’ information, ranging from their relative location and frequently visited websites to their personal interests.

Despite the obvious risks of unknowingly handing over personal data to tech companies, many don’t understand — or simply don’t care — about the potential consequences. Among Paly students, only 17 percent were very concerned with third party access to data, while 76 percent were at least a bit or somewhat concerned.

In the age of location tracking and personal data collection, is there any space left for privacy?

Past to present

The fear that technological growth will destroy privacy is not unique to the age of information; the invention of the camera also sparked similar concerns.

“Photography … captures the fleeting moments of interaction into a digital image that you can preserve forever,” says Arvind Narayanan, an assistant computer science professor at Princeton and an affiliate scholar of Stanford Law School’s Center for Internet and Society. “People thought that was going to be the end of privacy.”

Fast forward to the present, when the National Security Agency lies in the foreground of privacy concerns. In 2013, Edward Snowden leaked records of various global surveillance programs run by the NSA and governmental programs like electronic data mining and device location tracking.

In the Digitial Age, a new cast has emerged, threatening our privacy. Location services, online behavioral profiling and third party advertising networks all gather personal data on users, putting into question the positives and negatives of rapid technological change.

Beneficial or not?

Many companies justify data collection by advertising it as an effort to enhance user experience, but others question how much truly benefits consumers.

According to Narayanan, economists argue that any data shortening a transaction ultimately benefits the user, as companies will pass on some of their savings to them. However, others say that data collection has a serious lack of transparency, which creates a power imbalance between the company and the consumer.

“Uses of data that are unequivocally good or unequivocally bad are pretty rare,” Narayanan says. “But I don’t think companies are specifically out to use data in ways that [are] hurting users.”

Benficial or not, online user tracking has vamped up as sites like Google and Facebook gain popularity. For tech companies, more users means more consumer information to gather, analyze and apply to improve user experience.

“Think about all the information you put into these services yourself every day,” says Rebecca Jeschke, the Media Relations Director and Digital Rights Analyst at the Electronic Frontier Foundation. “That is the data they [advertisers] have. They also have more — often your location data”.

Tracking your every move

Location sensitive applications and services have their benefits, such as finding nearby restaurants and attractions. However, Jeschke points out these services are often not clear enough to allow users to understand what is being done with their information.

“Location data is very sensitive, and it’s often not clear which apps are gathering location information … how long apps are holding on to your information and what they are doing with it,” Jeschke says.

Although location-based services don’t appear to have severe immediate consequences, the very idea of third parties collecting user’s whereabouts is enough to raise serious concerns.

Another aspect of user tracking is online advertising, which has thrived as companies gain greater access to specific user information. Narayanan says that increasingly fine-tuned advertisements yield a higher rate of successful e-commerce transactions and allow for easier consumer targeting.

“Ad tracking discloses very detailed information about you — what you are interested in reading about, buying [and] what kinds of online communities you use,” Jeschke says.

Suppose that a consumer browses online and adds a pair of shoes to their shopping cart, but does not check-out and complete the purchase. Retargeting, one online advertising strategy, makes this pair of shoes follow the consumer aroundthe website and the rest of the web, according to Narayanan. Behavioral targeting lets companies direct certain advertisements to consumers based on frequently visited websites. Take, for example, the same shoe-shopping consumer. Companies might infer that they are interested in buying shoes and start advertising more specific products to that consumer.

Privacy programs

In the midst of increasing data collection, the complementary aspect of information protection has grown at a matching pace. One such program, Do Not Track, functions as a mechanism through which users can express their preference to opt out of user tracking, according to Narayanan. Do Not Track can be enabled in Google Chrome, Mozilla Firefox, Safari, Internet Explorer and Opera by going to the browser’s privacy settings.

“The cool thing about this [Do Not Track] is that this preference will be automatically communicated to any companies that are maybe in the business of online tracking, so users don’t have to opt out companies one by one,” Narayanan says. “The alternative would be quite cumbersome, given that there are over 100 major companies involved in tracking your browsing online.”

Typically, invisible trackers are embedded in the pages that consumers browse while on the web.

“Those [trackers] might be on Google in the form of their double-click advertiser network,” Naryanan says. “It could come from companies specifically in the online advertising business; it could come from companies that play a part with data brokers and such. Each of these companies is, technologically speaking, in a position to collect the record of all of the webpages to which you browse.”

Although the efforts for privacy protection are promising, Jeschke urges people to keep pushing for consumer protection.

“The deal reached in California for more clear and accessible privacy policies is one step, but another is to go the extra mile and actually engineer in strong privacy protections from the start,” Jeschke says. “I don’t want a future where if I’m not constantly super-vigilant, then I lose all my privacy and it’s my fault. That doesn’t have to be the case, unless we give up.”

Protect Yourself

An important part of privacy involves actually enacting steps to protect personal information. With little protection available on the Internet, users must take necessary precautions surrounding online privacy. Teens especially have a tendency to disregard the prominence of privacy protection. Narayanan warns against this type of thinking.

“Especially when people are ready to get their first job, they start worrying about what potential information employers have about them,” Narayanan says. “It’s really thinking about your future and how information online about you is going to affect you. It’s not something, necessarily, that can hurt you today, but it might do so in the future, so always be aware of that.”

Narayanan suggests that users regularly set aside time to check up on privacy threats and keep track of their online presence.

“I think learning about privacy should be an inherent part about how you learn about new technology, and not some separate sort of thing,” Narayanan says.

He regularly keeps up with new privacy threats and searches to find updates about himself online. Overall, he says, he sets rules about the content he posts, to whom he posts and the photos he is tagged in.

Although the process of protecting personal data may seem cumbersome and overwhelming, Jeschke emphasizes that more protection always offers more defense.

“The data collection that’s happening right now is wide-ranging and hard to track, so unfortunately, you have to be suspicious by habit,” Jeschke says. “If not, marketers and the government may know way more about you than you are comfortable with.”

In light of the rather ominous tracking and gathering of personal data, Narayanan reminds users that privacy will continue to exist as technology grows.

“The bottom line is that there really is no evidence at all that privacy is becoming harder, or is going away, and with new technology, we gain the ability to protect our privacy in new ways,” Narayanan says. “With some data collectors, we lose some aspects of privacy, but overall, I think the conclusion is we always move to a new equilibrium. New generations always learn to coevolve with new technologies and adapt to them, and I think that’s what we’re seeing with privacy, as well.”