Farha Andrabi presses her hijab-covered forehead against a colorfully embroidered prayer rug on her living room floor and mutters in Arabic. Her voice is a quiet but purposeful melody that fills the room. On her right is her 11-year-old son, Abdullah Navaid, who follows her lead as he fidgets with his hands.

“Allahu Akbar,” Andrabi repeats with Abdullah — God is the greatest. Although in America, this phrase often brings to mind a picture of foreign jihadists, to Andrabi, it means that she is only obligated to follow God’s rules.

“Allahu Akbar means that no one is the boss of me except God,” Andrabi says. “I am the boss of myself.”

There’s an intimate atmosphere as Andrabi and Abdullah complete three prayer units, which each consist of standing up, bowing and prostrating, or laying oneself flat on the ground face downward. The only reminder that Andrabi and Abdullah are praying in their living room and not a mosque is the smell of baked chicken fingers wafting through the room and the sound of Huda Navaid, a 2015 graduate of Palo Alto High School and current Santa Clara University freshman, typing on her computer. Noor Navaid, Huda’s sister and a Paly freshman, watches her mother and brother attentively.

After five minutes, Abdullah stands up and sheepishly declares, “I’m done,” and retreats to his room while beatboxing. Andrabi lingers, her head still pressed to the ground, and finally says, “Assalamu’alaikum warahmatulahi wabarakatuh” — may the peace, mercy and blessings of God be with you.

The Navaids feel a deep connection with their religion, which, according to them, serves to spread love and understanding.

Muslim families like the Navaids have recently had to navigate through newfound but deep-rooted Anti-Muslim sentiments that have permeated the American media and political landscape, creating challenges within their day-to-day lives.

[slideshow_deploy id=’10058′]

[divider]The Rise of Hate Crimes[/divider]

The expansion of radical Islam by terrorist organizations like the Islamic State of Iran and Syria and Al-Qaida and recent terrorist attacks on European and American soil have severely exacerbated tensions between the Western world and Middle East.

One consequence of these attacks is that fear drives some to make sweeping judgements about the Islamic community, labeling Muslims as hateful and violent. As a result, hate crimes against Muslims have spiked, tripling since the Paris and San Bernardino attacks, according to the New York Times.

These hate crimes have reached the Bay Area and Santa Clara County. On Dec. 18, 2015, for instance, a state correctional officer went on an anti-Muslim rant towards a group of Muslims praying at a park in Castro Valley and threw her coffee in one Muslim’s face, according to the San Jose Mercury News.

[divider]The Navaid Family[/divider]Anti-Muslim acts are nothing new to the Navaids who have experienced anti-Muslim prejudice in Santa Clara, Iowa and Nashville before moving to Palo Alto.

When they first moved to Palo Alto 16 years ago, both Asad’s and Andrabi’s car tires were slashed within the span of a week. When Andrabi took her car to the shop, the mechanics found pieces of metal in her tires and a piece of plastic tied around the exhaust pipe.

“Those things had never happened to me before,” Andrabi says. “So we did end up calling the police just to show that if someone was trying to be funny with us, we would resort to getting aid from the law.”

At Paly, Noor has not experienced anything blatantly Islamophobic or received many stares because of her hijab. Instead, she says she has received support from her peers and teachers, especially following terrorist attacks.

“After the Paris attacks, my English teacher came up to me the week after and said, ‘If anybody says anything to you then just tell me or tell an adult and just know that we’re all there for you,’” Noor says.

Andrabi, on the other hand, did not receive support after a terrorist attack committed by Muslims. On the morning of the San Bernardino shootings, she walked into the gym and people stared at her, turning to their friends to express discomfort or concern. At that point, the police had not pinpointed the perpetrators or the fact that they were Muslim.

After leaving the gym and heading to pick up her son at Walter Hays Elementary School, a man started to follow her car. When she stepped out of her car, he shouted anti-Muslim slurs at her, and called her a “stupid Muslim” for making a legal right turn at a red light.

“I was just thinking it was a bad day.” Andrabi says.

It was only after she saw the news in her son’s dentist’s office that it started to make sense. To her, the San Bernardino shooting seemed to create an instant fear and hate toward those who look like her.

Later that night, the Navaid family awaited more details from the news.

“Whenever something crazy like that happens, you’re just praying that it’s not Muslims,” Noor says.

As Noor reflects on the recent terrorist attacks, her mother and father, Navaid Asad, listen attentatively. Abdullah then describes an instance in which a classmate called him “ISIS.”

“He didn’t even know what it meant,” Abdullah says. “So, first I sent a letter to Obama because I was like ‘I’m done with this.’ And then I talked to my principal and everyone in fifth grade eventually knew about it.”

The principal took care of the incident and Abdullah was given an apology, in which the boy admitted that he did not know what he was saying.

“Why was he saying it?” Andrabi says. “Because that’s what he gets from the media.”

[slideshow_deploy id=’10060′]

[divider]Casual Prejudice[/divider]

An undercurrent of racism against Muslims also exists in Palo Alto’s relatively progressive community, according to other Muslims in the city, who say they see subtler racism that often goes under the radar.

Paly junior Aisha Chabane has faced such casual prejudice.

Often times when she tells her peers that she is Muslim, she is sometimes met with extreme surprise, as if there was no chance that Chabane, a light-skinned and non-hijab-wearing girl, could be Muslim.

She specifically remembers the astounded reactions of her two friends when she told them, as they responded, “That can’t be true,” and “you’re lying.”

“I guess you have a perception of what a Muslim looks like and what a Muslim is so then it comes as a shock,” Chabane says.

Much of so-called “Islamophobia” has more to do with racism targeted toward Arabs than religious-based discrimination, according to Chabane.

“I don’t really experience what women who actually wear [head]scarves experience,” Chabane says. “I don’t receive as much of the same criticism as I know many other Muslims do because of the color of their skin or the way that they dress.”

Nevertheless, not being easily identifiable as a Muslim has allowed her to hear the casually unkind comments made about her religion. When she was a counselor at a summer camp, a junior counselor proclaimed that all Muslims were terrorists, unaware that Chabane herself was Muslim.

She also says that she often witnesses people at Paly shouting “Allahu Akbar” in an aggressive manner, implying that it is a violent or extremist phrase.

“I sit there and think, ‘Is that what you guys think?’” Chabane says, “Is that what you think Muslims are like?”

Yusuf Rizk, a Paly junior and Muslim, faces the same sort of inconspicuous prejudice that Chabane does.

“There’s always the occasional 9/11 joke or the friend yelling ‘Allahu Akbar’ or something,” Rizk says.

He has gradually become numb and accustomed to the remarks, proclaiming that it’s more of an annoyance than anything to him.

“Eventually it [anti-Muslim comments] had no impact,” he says. “If someone yelled at me today, I would probably have a talk with them about cultural respect.”

[slideshow_deploy id=’10064′]

[divider]Misconceptions About the Hijab[/divider]

According to Huda, a prevalent source of this same casual prejudice is the perceived oppression of Muslim women through modest clothing.

In the seventh or eighth grade, a fellow student at Huda’s all-girls school posted a picture on Facebook of her wearing a long skirt. She was judged in the comments for being oppressed for having to cover up.

Muslim women experience similar judgment about wearing the hijab, which supposedly oppresses their sexuality.

“Muslim women are told that they are less beautiful than women who don’t wear a hijab,” Huda says. “‘We’re culturally shamed, religiously shamed and made to feel like we’re less beautiful.”

Yet Islam and the hijab are the opposite of oppression, she says.

“Islam is empowering for women,” she says. “Its [A woman’s] value is based on her personality and relationship with God and other people, not on men. It’s one of the most empowering movements of feminism, because it allows men and women to be equal.”

[divider]Redefining Islam[/divider]

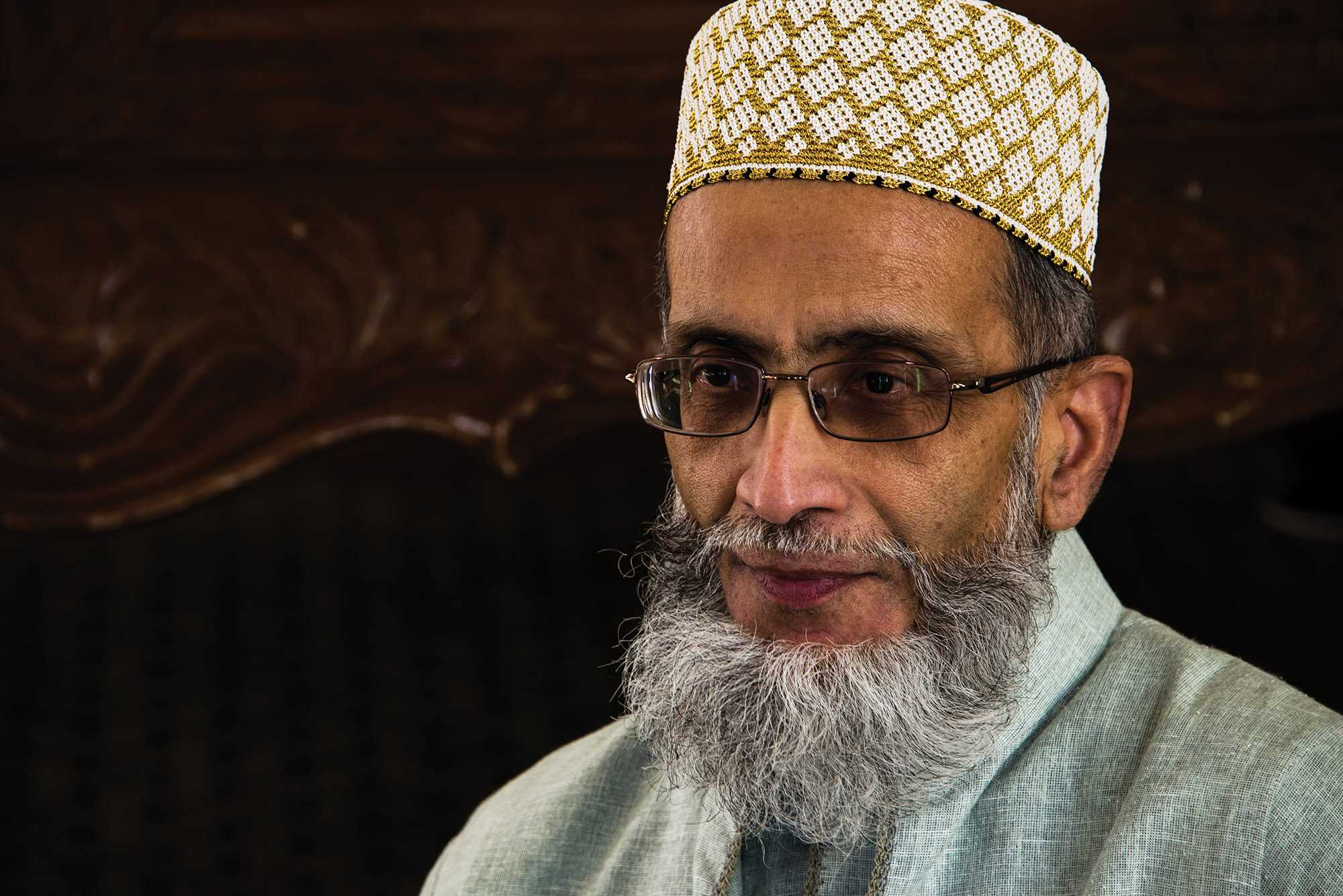

Beside the crowded highway entrance at San Antonio Road is the Hatemi Masjid, one of California’s four mosques made for the Dawoodi Bohra community, a primarily Indian and Pakistani group that follows Shia Islam. The masjid is imposing — a huge structure lined with gold and embellished with intricate details and designs, each with meaning. Inside, the mosque’s aesthetic is a unique juxtaposition of modern and traditional, with abstract-looking chrome chandeliers and LCD screens clashing with the takhat, a chair for the imam, Muslim priest, to sit on during prayers, and mihrab, a niche in the wall of a mosque pointing towards Mecca, a religious center in Saudi Arabia.

Zoaib Rangwala, the community secretary and head priest, emphasizes the progressiveness of the Dawoodi Bohra. He immediately offers M&Ms to visitors, a modern twist to a traditional custom of offering sweets to guests, and uses a Powerpoint presentation to explain the values of Dawoodi Bohra.

“We are your engineers and your doctors,” Rangwala says. “We’re your typical geeks.”

Rangwala stresses the strong values of Dawoodi Bohra, which include no interest in financial transactions, education for all, caring for the environment and pride in one’s country.

“The barbarity of ISIS is not what we are,” Rangwala says. “It is not what the Dawoodi Bohra is, it is not what Islam is.”

He goes on to talk about who he is — a normal Bay Area resident. He loves Stephen Curry. He went to University of California, Berkeley.

“Your aspirations are what our aspirations are,” Rangwala says. “You want to be something great, you want to be a physician, you want to be a psychologist, you want to be a Ph.D. Those are the same aspirations that we have, that our children have and that’s how we go about our lives.”

[slideshow_deploy id=’10080′]