Managing monkeypox: Disease echoes AIDS/HIV stigmatization

Blister-like lesions and a painful rash appearing across the body are some of the tell-tale signs of a monkeypox infection. Other symptoms include fevers, muscle soreness and exhaustion. Global outbreaks this summer brought the virus into the public eye, and although cases are currently declining, discriminatory associations with racial and LGBTQ+ groups have remained.

Monkeypox is a broad term, much like the phrase “coronavirus.” First coined in 1958 by Dutch scientists studying monkeys in captivity, it describes a virus in the same family as variola or smallpox, with slightly less severe symptoms.

Although the virus is commonly known as “monkeypox,” authorities like Santa Clara County Public Health Officer Dr. Sara Cody discourage the use of the term and suggest “MPX” (pronounced “EM-pox”) instead. As the first human cases were recorded in Africa, the phrase “monkeypox” has an association of the disease with Black people, according to The New York Times. “Monkeypox” also incorrectly implies the disease originated in monkeys, while the first cases actually occurred in rats or rodents.

“We have to be careful we don’t fall into that same trap of stigma [with MPX].”

— Dr. Catherine James, San Francisco Health Network

The disease has remained endemic in 10 African countries since the first human case, which was recorded in the Democratic Republic of Congo in 1970. A low infection rate in the Americas and Europe meant it remained obscure to most of the Western world until cases began popping up globally this summer. At the time of publication, the CDC has reported over 23,893 confirmed cases in the United States.

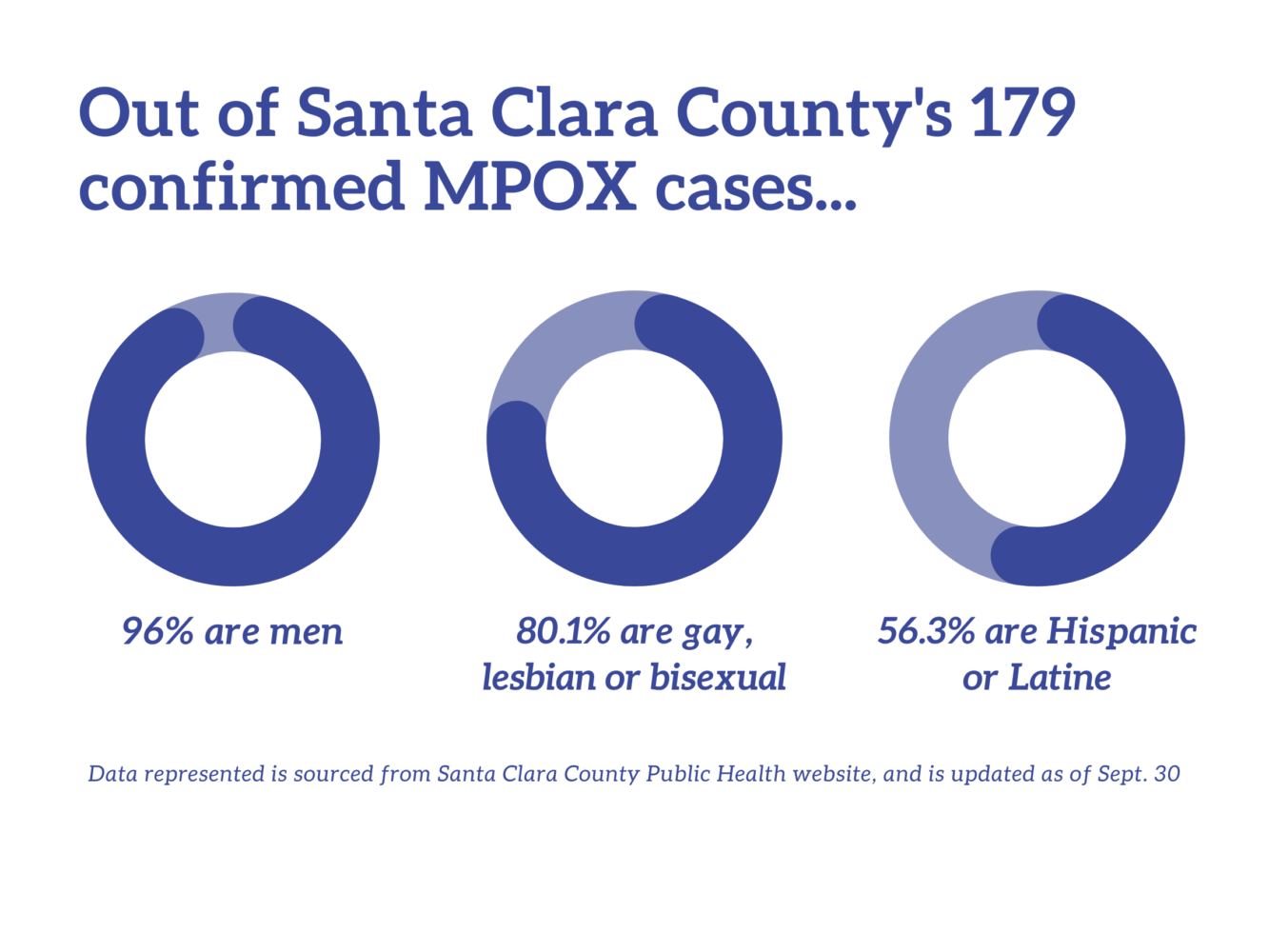

Over 54% of Santa Clara County’s 167 cases affected Hispanic individuals, over 95% were male and over 67% were gay, according to the county’s public health website.

Although MPX vaccine eligibility is currently being emphasized for gay and bisexual men, Cody emphasizes the importance of understanding the facts.

“It’s a virus; it could actually affect anybody with an infectious rash who has a lot of skin-on-skin contact with somebody else,” Cody said. “In the United States and California and Santa Clara County, it was first introduced into a social network primarily of men and trans men who have sex with other men, and so most of the cases are among men [who] identify as gay.”

Comparison to HIV/AIDS

Public misconceptions about how MPX spreads echo reactions to the AIDS/HIV crisis of the 1980s and 90s. Dr. Catherine James, who has worked with the San Francisco Health Network for 20 years, was a medical student at Ward 86 — the first dedicated AIDS/HIV clinic in America — at the height of the crisis, and went on to serve as director of the Maxine Hall community health center for over a decade. According to James, the association between AIDS/HIV and queerness deterred many people, especially people of color, from seeking treatment at specialized clinics.

“The way people responded to COVID and MPX labeled entire marginalized communities with a disease they aren’t responsible for, which isn’t fair.”

— Connor, anonymous Paly student

“A lot of my Black or Latino patients who came to get care for HIV at Maxine Hall came there because Ward 86 was known to be ‘the HIV clinic’ … and people didn’t want to be seen as having HIV,” James said. “We have to be careful we don’t fall into that same trap of stigma [with MPX].”

The association between queerness and MPX has not been missed by the Palo Alto High School community, and many recognize the danger of that association.

“It’s true that gay people are disproportionately affected by monkeypox, but it forms an image that gay people are the face of the disease,” said Connor, a gay Paly student whose name has been changed to protect his identity.

“The most important things for schools is to be well-informed.”

— Dr. Sara Cody, Santa Clara County Public Health Director

Connor, who is Asian American, also pointed out parallels with the COVID-19 pandemic response.

“The way people responded to COVID and MPX labeled entire marginalized communities with a disease they aren’t responsible for, which isn’t fair,” Connor said.

Connor echoed James’ concerns that stigma could contribute to low-case reporting, even for those with symptoms.

“Because of that label, people will be scared to report cases, and people are still scared to be perceived as gay,” Connor said.

In an anonymous survey of 226 students conducted by Verde Magazine, 59% of students said that they would feel scared to let others know if they had contracted MPX.

Fortunately, contracting MPX shouldn’t be a cause of severe concern to high schoolers at this time, according to Cody. In fact, zero cases have been reported for people aged 17 and under in Santa Clara County, and cases are overall in decline. However, Cody said young people can still do their part to fight the misinformation about the disease.

“The most important thing for schools is to be well-informed,” Cody said. “Fighting stigma is the most important thing that Paly students can do. Just to talk openly about how it’s spread and how it’s not.”