The teacher’s arm rests naturally upon the back of her student’s bright green wheelchair as she looks over his geography homework. Across the table, a young girl with a pink medical mask works through an algebra problem aloud as her teacher nods encouragingly.

While students at Palo High School take their seats, hand in their homework and raise their hands for participation credit, just across the street at the Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital School, a father embraces his daughter’s teacher in tears.

“The school was the best thing that ever happened to her,” says Bob Atherton, father to LPCH alum Becca Atherton.

For 25-year-old Becca, life in a hospital is far too familiar. Born with several cardiac anomalies, she has endured countless surgeries and procedures that oftentimes required her to spend weeks at a time confined to a hospital room.

“I remember driving up here,” Bob says, recounting their first visit to LPCH. “We drove by the hospital, but we kind of drove around the block because she [Becca] didn’t want to go in. She didn’t want anything thing to do with it.”

Becca was 13 when she first came to LPCH for treatment. During her two-week stay, when everything was strange and frightening, one of the only things that provided her with some sense of normalcy was the one-room classroom on the third floor.

“Yes, we have to meet the standards, but it’s in an environment where it’s kind of a gift if they can come to school.”

— Thayer Gherson, LPCH teacher

The classroom bears no resemblance to a hospital; shelves overflow with books, and the walls are hidden by artwork, photographs, maps and practically anything that can be fastened with Scotch tape.

The room is divided into two sections, one for the elementary and middle school students and the other for high schoolers, by a partition that remains open most of the time.

Established in 1924 by Lucile Packard herself, the hospital’s school has been running in collaboration with the Palo Alto Unified School District for 94 years with the ongoing mission of providing quality education to critically and chronically ill children.

“I’d say, of all the children’s hospitals, there may be four or five others in the nation that have a school as structured as the program here,”says Thayer Gherson, a high school teacher who has taught at LPCH for 24 years.

The LPCH school has the unique ability to support students coming from other school districts in addition to those who live in Palo Alto. Though the hospital tries to keep the students enrolled in their local schools, districts are often not equipped with the resources to support them while they are away.

These kids are often enrolled in PAUSD during their stay at the hospital and then transferred back to their home school district to ensure that they are able to receive school credit despite the unpredictability of their medical situation.

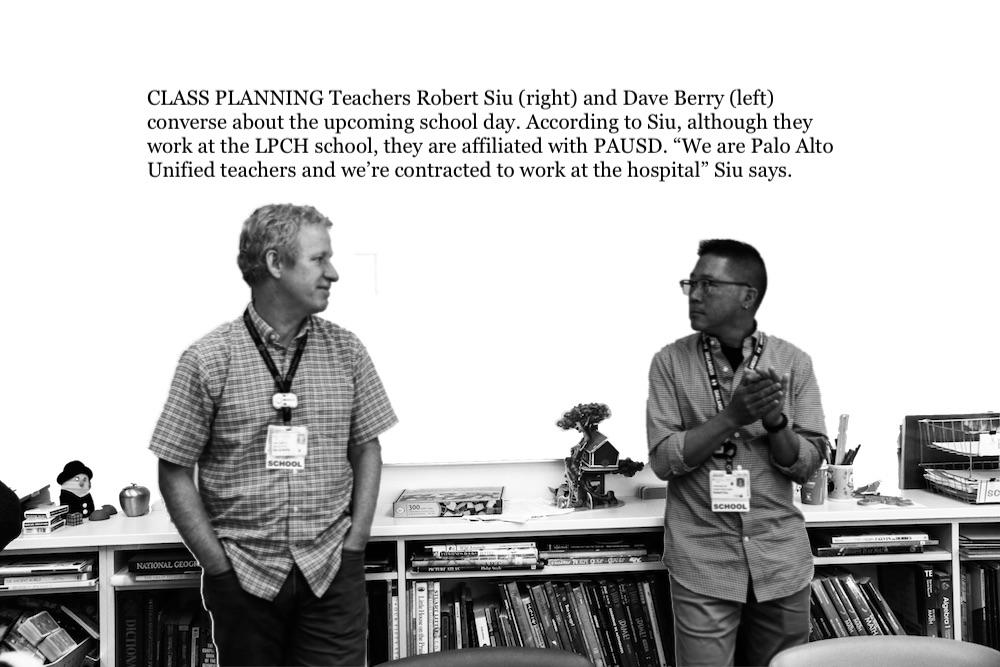

“There is no usual,” says Robert Siu, a middle school teacher at LPCH.

The school runs hour-to-hour; class sizes vary from three to 25 students depending on how the kids are feeling or where they are in their treatment plan; some kids require bedside lessons, as their bodies are too vulnerable to infection to be physically in class; some come in with work from their home schools, while in other cases the teachers must create a tailored curriculum from scratch.

“Yes, we have to meet the standards, but it’s in an environment where it’s kind of a gift if they can come to school,” Gherson says. “To see kids learning that way is so much better than ‘Oh, I’m writing out my homework and copying someone else’s just so I can get it turned in so I can get my A’.”

Everyone within the one-room school is on a first name basis. During a Tuesday morning session, Gherson sits right next to her student, pausing the lesson once in a while to crack a joke and make him smile.

“Part of what we try to do is make this a very safe environment,” Gherson says. “Nobody judges; you have a bad day? You have a bad day.”

To Gherson, the ability to tailor learning to what a child really needs, whether it is related to school or not, has in many ways allowed her to grow as a teacher.

“I have children who are dying,” Gherson says. “One of the boys came to me and said, ‘The one thing I want to do is get my driver license.’ And so we did Driver’s Ed, and his [home] school rebuilt a car and brought this incredible Mustang down and we drove it in the parking lot.”

Although students come and go, the connections built within the classroom do not disappear when they leave the hospital. In fact, many of the teachers stay in touch with their students who often return to visit.

Becca is a particularly special example.

Every year, she and her family make a special trip from Arizona to attend the LPCH school prom. Even as a young adult, she is still involved within the classroom.

“Anytime she comes into the classroom everybody knows her,” Gherson says. “She’ll ask ‘Who needs help?’ and I let her be a tutor, and she just goes.”

Becca has been in and out of LPCH for the last 12 years, and decided this year to stop treatment and spend time with her family at home.

“It [the school] was the thing that really turned her around,” Bob says, pausing to steady his voice. “She [Becca] had never been to a place where they had a school where you could be with kids that have the same issues; where you have unbelievable teachers that take an interest in everything that that kid had going on.”

Both Gherson and Siu agree that there is no job that compares to the work they do at the LPCH School. To Siu, his students are inspiring. To Gherson, the teaching is beyond rewarding. For Becca, it’s just a chance to go to school, sit beside students like herself, open her notebook and raise her hand for the sake of learning. v