A FRIENDLY GESTURE

Kevin Whittaker, a San Francisco resident and Palo Alto-based attorney, strides into Palo Alto High School’s photo studio with an air of confidence, his well-fitted suit pressed clean and his hair neatly gelled. The Vegas rest

aurant and clothing company owner set the record for the longest handshake in 2008, fulfilling his childhood

dream of being featured in the Guinness Book of World Records.

As a child, Whittaker wistfully flipped through pages of the widely-read book, hoping to someday achieve the fame that he associated with record holders. The seemingly unattainable lingered in the back of his mind throughout high school and college.

The decision to move forward with breaking a record came mid-way through Whittaker’s successful career as an attorney, when he stumbled upon a radio show in which DJs were discussing a boy who had worn the most number of shirts on the David Letterman show. He went on to brainstorm which records were the easiest records to break.

Whittaker acknowledged that he might not have the talent nor capacity to break a record requiring athletic stamina or innate skill, so he decided to do just what the DJs had suggested: shake hands.

Energized by the more realistic prospects of achieving a record, Whittaker contacted his high school friend Cory Jens, who had grown up in the same rural Iowa town as him and leaped at Whittaker’s proposal. The pair speedily received the go-ahead from the Guinness Association and contacted journalists from the San Francisco Chronicle to monitor the event.

Whittaker staged the event at San Francisco’s ferry building, a bustling epicenter of tourist and commercial activity. He welcomed onlookers and drew posters “announcing their prominence,” elated to finally be achieving their dream.

Excitement waned, however, as arms grew sore and the sun dipped below the horizon. In an effort to alleviate discomfort, Whittaker and Jens decided to switch off on who would perform the actual shaking motion, and the record was broken at 10p.m. in the lobby of a Hyatt hotel, which the pair had taken shelter in from the cold. Neither record setter anticipated the overwhelming response that would come the following week.

“The [San Francisco] Chronicle ran their article on Tuesday, and within 24 hours the Associated Press picked it up so a version of that article got published in almost every major news publication in the world,” Whittaker says. “I have 300 copies of newspapers in languages like Russian and Thai and all these high school classmates started calling me.”

Apart from the unexpected global fame that came with setting the record, Whittaker was also interviewed on one of Howard Stern’s television shows and flown out to New York City by the Wall Street Journal for a “shake-off.”

College students from Los Angeles broke Whittaker’s record a few months after the initial record setting, and an Australian man with the “most number of records broken” was quick to claim the record from the college students. Despite coveted title’s short-lived nature, Whittaker regards the event with fond memories.

“I think it’s a good story, something to do on a Monday afternoon,” Whittaker says. “It wasn’t a true feat of some great athletic accomplishment or letting your fingernails grow for seven years — it was a pretty short moment in time that we will able to capitalize on.”

Whittaker encourages aspiring record holders to give their dreams a shot — students can plan the events to act as fundraisers for the cause of their choice.

“There are a lot of records that are definitely attainable, even if you don’t have any crazy special skill that nobody else has,” Whittaker says.

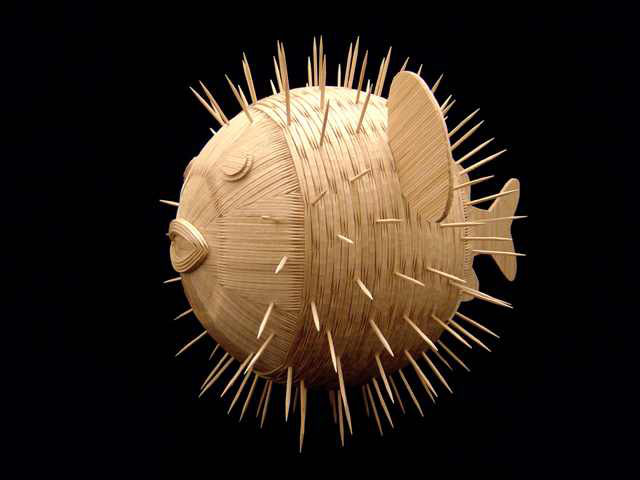

TOOTHPICK SCULPTOR

Steven Backman, a San Francisco native, holds the record for creating the smallest toothpick sculpture, a replica of the Empire State Building built from a single toothpick and created with glue and a razor blade.

Backman’s work has been featured in San Mateo’s maker faire and purchased by clients for up to $1000. Over the years, the scope of his projects expanded miniscule sculptures to large recreations using thousands of toothpicks.

Backman began his lifelong journey working with toothpicks at age five, fascinated by the idea of making recognizable art from a medium normally used to pick teeth. He went on to major in Industrial Design, continuing to teach himself the nuances of toothpick-sculpture building. While Backman has a day job, he often works for up ten hours at a time, digital distractions muted and his focus directed solely towards his projects.

Backman decided to attempt breaking the record 15 years into his toothpick endeavors. The path to success wasn’t without its struggles — an impatient person, Backman smashed one of his figures as a second grader, injuring his hand.

Over many years of failed experimentation, he learned to persevere, stopping at nothing to achieve his father’s wish: that he achieve a world record.

“I was always taught to never take no for an answer,” Backman says. “I needed to have a ‘yes’ attitude and I never gave up on my dream.”

ROWING PRODIGY

Even closer to home is Gordon “Trey” Holterman, a senior at Sacred Heart Prepatory, who set the record for fastest ten kilometers erged by people ages 15 to 16. Holterman initially started rowing three years ago, with the intention of building his body up for the basketball season and quitting rowing soon thereafter.

Holterman set the record for the greatest distance rowed on a rowing machine in 30 minutes by accident during a routine exercise with his teammates.

“I knew it was a fast score — I had almost beaten my 5k so I knew I had done pretty darn well,” Holterman says. “Then a kid on my team just quickly looked it up and said ‘Trey you broke the world record!’”

After having his record broken by a teammate shortly thereafter, Holterman trained with vigor and once again claimed the record. He relishes opportunities to excel by putting in hard work, and believes that though rowing is a lesser-known sport, it was just the right facet for Holterman to channel his energy into.

“I think it’s interesting because it’s a sport that not that many people are competing in, but to try to be the best in anything is very cool,” Holterman says. “I wanted to prove to myself that if I wanted to do a sport that is lesser-known and much less recognized, I was going to try to be the best in it.”

Looking into the future, Holterman is going to continue to pursue rowing in college, and hopes to break even more records.

“I’m definitely going to keep going for new records since there’s no higher goal to set than being the best in the world,” Holterman says. “It always keeps me focused and determined.” v