After the bulky orange “get ready” sign flashes fingers begin to tap upon the smartphone screen in a rhythmic beat guiding the pixelated bird, the main character of the viral game “Flappy Bird,” between rows of green pipes. As each cheerful ding rings out, the finger begins to move erratically as the bird nearly starts to touch the pipes. All of a sudden, the world shakes and the screen goes white. “Game Over” blares across the screen. A hammer swiftly smashes itself onto the smartphone, and the black screen is webbed by silver cracks.

Although destroying a smartphone with a hammer seems ludicrous, it doesn’t fall far from the reactions people have towards the popular application Flappy Bird. People have obsessively played with it to the point where the creator of the game, Dong Nguyen has allegedly pulled the game off the application store due to concerns over the game’s addictiveness.

Addicted to apps

Games found on smartphones and the internet like Flappy Bird are addicting, and their impact can be found all around the world, ranging from robberies to death.

In China, there are actually rehabilitation centers for people whose love for games has turned into a medical disorder. With a combination of health and military drills these teenagers are taught the dangers of the internet and how to stay away from it. While boot-camp esque facilities are necessary when a person plays games for more than three days they should be called into play for everyday use.

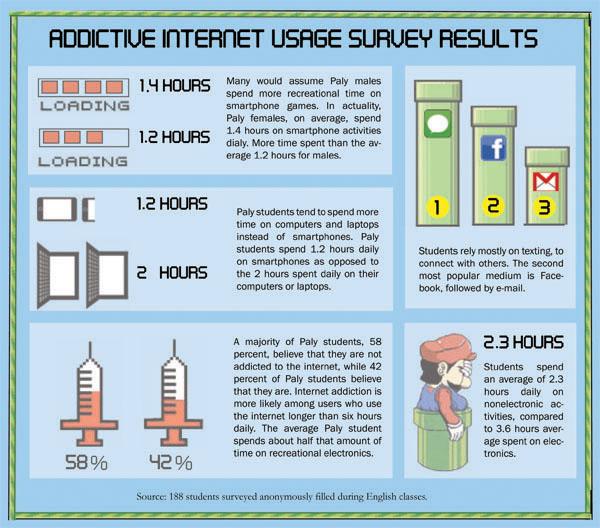

Addictions of this level are extreme and abnormal, but the fact remains that app use takes up big proportion of student’s time.

Palo Alto High School senior Freddy Killinson-Linn, who created an app game, cites the longevity of games as a factor in their appeal.

“I think what makes a lot of the conventionally addicting games so addictive is the fact that you’re never really done,” Kellison-Linn says. “You can always beat the next maze or fly through the next pipe, so there is tons of replay value.”

However, games do not just provide re-play value — it has been shown that they affect the brain in a similar way to drugs.

A presented at the British Neuroscience Association Festival of Neuroscience showed that when participants felt that they were about to win, the areas of the brain that were activated overlapped the areas of the brain that are activated when the person won.

In other words, losing often had similar brain reactions

to winning, although the two should normally trigger opposite reactions.

This means that the participant would feel successful even if they only came close to winning, which makes playing the game more appealing (and addicting).

A Community for Apps

Apps can also be used to bring a population together and foster collaboration on a community’s problems. One example of this is the Hack Palo Alto challenge, recently conducted by Palo Alto’s Chief Information Officer Jonathan Reichental.

“This challenge creates a forum for a public-private partnership in experimening with technology innovation for the benefit of community,” Reichental says.

The finalists were announced on March 13, and included ideas like imporving the use of public transportation and parking, ideas to support greater ommunity participation in city decision making and several solutions to support Palo Alto animals and pets, according to Reichental.

Future of Apps

Apps have already had a huge impact on the world, and continue to change the way our society works every day.

“The world is increasingly at our fingertips, wherever and whenever,” Reichental says.

However, Reichental believes that this new accessibility does not come without its challenges and new concerns. Despite the negative aspects of them, Reichental thinks that the apps will continue to become a bigger part of every day life, to levels unimaginable today.

“Ultimately, I think this shift is positive,” Reichental says “but I think we’ll all be surprised at the capabilities and unanticipated outcomes it enables in the years ahead.”