If James Franco is our most famous celebrity alum, and Jeremy Lin is our most famous sports star, surely James Hogue is our most famous con-man.

Notorious imposter James Hogue was not arrested in a car chase or in a police shoot out. Nor was he part of a drug cartel, a Ponzi Scheme or a smuggling ring. Instead, he was caught in a public library taking a break from living in his makeshift shack on the steep slopes of a Colorado mountain, where he lived alone for at least a year, according to Aspen police Detective Jeff Fein.

But Fein was impressed with the shack made out of two-by-fours, one-by-fours, plywood, small windows and a sloped roof. The walls were well-camouflaged with forest-green and brown spray paint, making it almost impossible to spot, and the large swathes of scrub oak surrounding it were nearly impenetrable.

Before we continue with Hogue’s story, know that the outrageousness of his living situation is not out of character. Hogue, infamous for posing as a student at Palo Alto High School in 1985 and Princeton University from 1986 to 1988, is a complex person. To write this story, we talked to his childhood friends in Kansas and those he deceived at both schools, and found that there is no consistent opinion of Hogue. Some claim he’s a malicious imposter, while others assert that he deserved to “succeed” to the extent that he had. We merely ask that you strap in and judge the strange life of James Hogue for yourself.

In February, Fein’s introduction to Hogue came in a confused call from an open space ranger about a hidden shack on Aspen mountain, Fein trekked to Hogue’s shack and knocked on his “door.” Upon hearing the knock, Hogue squeezed out of the small side window and took off into the woods, cleaning out the shack the next day, Fein told us.

Two months later, Fein received another call, this time about Hogue living in a “hole in the ground” on the mountain. A ski company employee later saw him in a private parking space moving large Eddie Bauer duffle bags into his vehicle and using a stolen parking pass. Fein ran the plate and determined the owner was Hogue, a 57-year-old Mission, Kansas native who had a couple of warrants out for his arrest.

“I started to do a little digging, put out his information to the papers, and, as a result of that, he was identified as being in the library the next day,” Fein says.

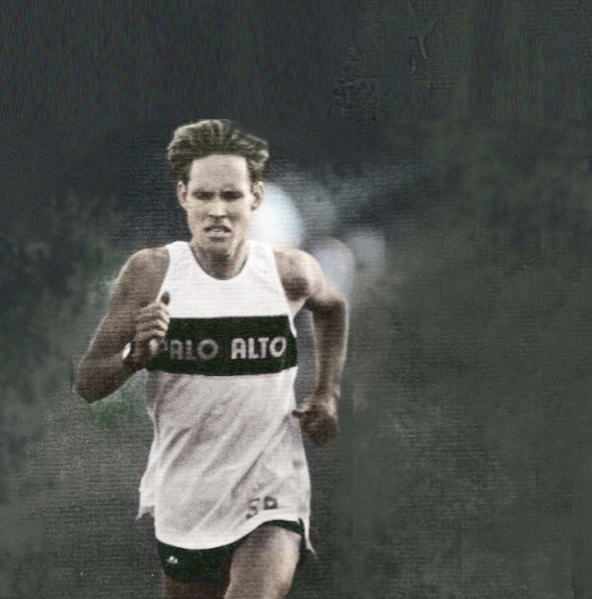

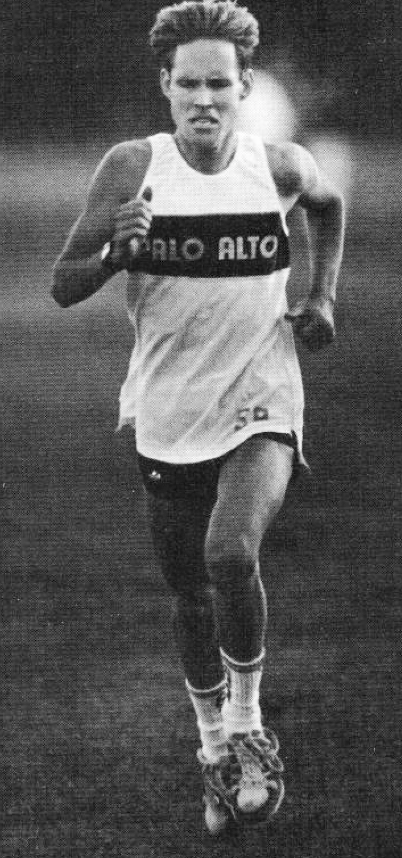

With a simple Google search, Fein also uncovered Hogue’s past of self-invention and identity theft as reported by publications like The New Yorker and New York Times. Fein found that a 26-year-old Hogue posed as a Palo Alto High School senior under the name Jay Huntsman for two weeks in 1985. He later created the persona of Alexi Santana, an orphaned farm boy with brilliant intellect and a talent for long distance running. As Santana, Hogue attended Princeton University for two years from 1986 to 1988; he was discovered by Renee Pacheco, a Paly graduate and Yale University student who recognized Hogue at an Ivy League track meet.

“I became fascinated with this story,” Fein says. “Anyone who has their own Wikipedia page is of interest to me.”

Fein and his colleagues later discovered that Hogue was stealing and selling sportswear and arrested him in Nov. 2016. In late March, he was sentenced to Colorado state prison for six years on charges of felony theft and felony possession of burglary tools, according to the Aspen Times. However, Hogue’s story stuck with Fein, much like it does for anyone who hears about his many identity transformations.

Fein found that Hogue was a man of brevity, only responding to the detective’s questions in a few short words. He didn’t seem malicious, but he did paint himself as a victim of the government and of social hierarchy and class structures. His long history of deception was masked by a pale, aged and relatively small-framed body, and, more than anything, he loved to run, so much so that he was often times willing to risk everything to compete.

Born in blue-collar Mission, Kansas to working-class parents, Hogue invented and reinvented himself from scratch, creating the image of the downtrodden orphan who, despite his hardships, was naturally talented.

Although his story has been forgotten by many Paly students and teachers, Hogue’s recent arrest prompted us to take a deeper look at the life of Paly’s most famous con-man and his twistedly American cycle of deceptive self-creation.

A stop at Paly

In 1985, Hogue approached Stanford University cross-country coach Brooks Johnson as 16-year-old Jay Mitchell Huntsman, an orphan who had lived on a commune in Nevada before his parents died in an automobile accident. Hogue asked if he could join the team; Johnson, amused by “Huntsman’s” ambition, directed him to Paly.

“I think it was the same day that I heard from the athletic director at Paly that there was a kid who had checked in at the district office to try and get connected,” says Paul Jones, Hogue’s cross-country coach at Paly who retired last year.

According to Jones, Hogue was provisionally accepted to the Palo Alto Unified School District with little trouble and routed to Paly where he unofficially joined Jones’ cross-country team.

Hogue, although shy and reserved, fit in well with the team. His teammates were moved by his story and were even more amazed by his fast race times during practice.

He also excelled in his short time in the classroom. Esther Wojcicki, Paly journalism teacher, taught Hogue in her senior English class. She remembers that he usually came into class late, but was very attentive and asked good questions. However, Wojcicki thought that he looked older than his peers.

“As a teacher, it was rude for me to even think that [he was older,]” Wojcicki says. “Even though he was very thin, you could see the shadow of his beard.”

Despite his apparent intellect in the classroom, Wojcicki recalls him rarely having interactions with other students.

“He seemed really smart, but he had no groups that he associated with,” Wojcicki says.

Hogue exposed

Hogue’s alias quickly began to unravel when he attended the Stanford Cross-Country Invitational on Oct. 7, 1985. Although he was not officially approved by the Paly athletic department, Jones and Johnson allowed Hogue to run at the event as long as he guaranteed that he wouldn’t cross the finish line. With his Paly uniform flipped inside out, Hogue was strides away from victory when he veered off, according to Jones.

His performance at the meet attracted the attention of local media, particularly Jason Cole, a young reporter at the now-defunct Peninsula Times Tribune. After doing some research, Cole discovered that Jay Huntsman, the alleged self-educated orphan, was actually the identity of an infant who had died two days after birth at Stanford Hospital. He confirmed the stolen identity with the real Huntsman’s parents, and exposed Hogue in the Tribune.

“Once he [Hogue] realized that he was going to get caught, he bolted,” Jones says. Even after over 30 years, there’s a tone of disappointment within Jones’ voice. “They [his teammates] all liked him. They were pretty upset that he pulled their chain when he left. It wasn’t like they hated him from then on. They were just really disappointed that he wasn’t what he said he was and that they had been bamboozled.”

He looked young. He said that he was an orphan. He was intelligent. He seemed to demand our sympathies. Why question him? There’s no reason to.” Jesse Moss, Paly alum and creator of documentary "Con-Man"

After Hogue left, both administration and students were left with unanswered questions. Arne Lim, a Paly math teacher who was in his second year of teaching during Hogue’s stint at Paly, was particularly baffled by his motives.

“We’re still scratching our heads every so often to say, you know, ‘Why in the world would someone do this?’” Lim says. “Honestly, from my perspective, it was just strange. It was something that I didn’t think could happen again, although obviously he’s been quite the imposter.”

Hogue’s easy entry into the school district forced the administration to take another look at safety procedures and athletic rules. According to Jones, a year after Hogue ran in the Stanford Invitational, the Central Coast Section created a much stricter rule against athletes competing in games and meets before being cleared by a school district.

A Gatsby story

In the early 2000s, Paly English teachers Trinity Klein, Mike McNulty, and others taught The New Yorker’s published piece about Hogue in tandem with “The Great Gatsby” in American literature.

Jesse Moss, the creator of “Con-Man,” a documentary about Hogue’s life, who attended Paly with Hogue, also made the connection between Hogue and Jay Gatsby, the iconic protagonist who attained wealth and status through self-invention.

“I think fundamentally the film [“Con-Man”] was also about social class and America,” Moss says. “That sounds kind of clinical, but it was a kind of an X-ray of class in America. I love that he, like Gatsby, was able to transcend his low birth to attain this high position, but he was, like Gatsby, brought low. I think that makes it an extraordinary American story.”

However, the lesson disappeared years ago, and memories of Hogue’s strange stop at Paly have somewhat faded.

“When I think about it now, I laugh,” Lim says. “I laugh at the fact that someone would want to do that; that someone was successful to some extent to get away with it for a while. Was it harmless? Some would say yes, some would say no, because again it brings up a heightened awareness about safety, as well as a question about what is this person’s true motive. I don’t know. I laugh. I smile about it. I have friends who think about it also and just go ‘Yeah, that was really weird,’ but we just pass it off.”

Moss’ thoughts

As a student attending Paly while Hogue was there, Moss questioned why any 26-year-old would pass themselves off as an orphaned teen. But, rather than feeling betrayed, Moss was simply curious — a curiosity that later led him to make “Con-Man.”

“More importantly I think that we are trusting — that’s human nature. I think we [the Paly community] wanted to believe his story and we had no reason to doubt him,” Moss says. “He looked young. He said that he was an orphan. He was intelligent. He seemed to demand our sympathies. Why question him? There’s no reason to. That accounts for his success in part, that he was able to present himself and present his story in ways that we believed.”

While creating “Con-Man,” Moss tracked down and interviewed Hogue while he was living in Colorado. But, in some ways, Moss was disappointed. Hogue wasn’t the charming and cocky criminal that he had imagined; in reality, he told us that Hogue was withdrawn and constitutionally incapable of being analytical, self-aware or emotionally expressive.

“In fact, I found that the people who knew him told his story better than he did,” Moss says. “In a way that makes sense, because he was a kind of construction or projection of their collective, desires, fantasies, wishes. But that didn’t change the fact that he was kind of disappointing in some ways, but human, right? He was ultimately human and that’s what’s interesting.”

Kansas origins

When Keith Mark heard that we’re writing a story on his childhood friend James Hogue (or Jim, as his friends in Kansas call him), he jokingly — and we only later appreciated the irony of this — asked if we’re “actually student reporters, or just 26-year-olds pretending to be student reporters.”

Mark’s path in life seems to be the antithesis of Hogue’s. The founder of his own law firm and the co-host of a talk show with professional wrestler Shawn Michaels, Mark lives a high-profile life in the small city of Mission, Kansas.

Mission is blue-collar and working-class — a place where fathers — including Mark and Hogue’s — worked on railroads and their high school cross-country team prayed before meets. It was in the small Southern town of Mission where Hogue and Mark became friends. In fact, Mark was probably Hogue’s only close friend. They met in middle school when they ran cross-country together.

“He was one of the smartest kids that I’ve ever known,” Mark says. “[A] very good, polite kid. Never in any trouble. Trained all the time. Had a tremendous gift to run. Literally the best runner — could’ve been Olympic class. He had big time talent is what he had. But, when we were in high school, he was very much an individualist and he did not like to be told what to do.”

I got a kick out of the fact that he had duped Princeton University out of tens of thousands of dollars. I think it’s pointed that a kid from where Jim and I come from — Kansas City, Kansas — had the savvy to pull one over on all those rich people.” Keith Mark, James Hogue's childhood friend

Hogue’s maverick spirit led him to reject their high school track and cross-country coach, Wayne Hoblemann. A man who believed in his Christian faith wholeheartedly and a coach for youth of all races from low to middle class families, Hoblemann recalls Hogue’s senior year, when he refused to run for cross-country.

“The principal called me and said, ‘Why isn’t Jim Hogue running?’ because he was one of the best runners in the state. I said, ‘He doesn’t like my workouts. He doesn’t think I know what I’m doing.’ Principal said, ‘As long as he wins, let him do his own workouts!’” Hoblemann says with a hearty laugh. But, he deeply regrets his decision to let Hogue train on his own. As the leader of the Christian League of Athletes, Hoblemann has seen the importance of having direct involvement in adolescent’s lives.

“Some people’s lives are turned around because of that [youth groups], but I didn’t do that for him,” Hoblemann says. “I guess I regret just putting up with him. Maybe, he would’ve gone out in the world and done what I would’ve liked to seem him do.”

Despite Hogue’s lack of cooperation with Hoblemann, he ran phenomenally his senior year, so well that he could have been recruited anywhere (He eventually ran at the University of Wyoming from 1977 to 1978.) After winning the state two mile in track, Hogue initially refused to run the mile, but Hoblemann insisted, signing Hogue up for the event. He was winning three and three-quarters laps into the race when, instead of achieving another state title, he just stepped off the track.

“That was Jim’s way,” Mark says, “Jim was the guy that would win the meet by a longshot and then while the other kids were finishing up, he would go to his dad’s car and put on a full suit with the jacket and the tie and the slacks. When they were handing out the medals, the other kids would be standing there in their sweats, just finished running, drinking their Gatorade and Jim would show up wearing a sports jacket and a tie and he would get the first place medal.”

Hogue was known for these strange quirks. Hoblemann recalls how Hogue once attended a high school miles away from his house, instead of his intended high school, until his school’s administration found out. Hogue, Mark and Mike Shore, another one of their friends and a fellow runner, used to sneak into golf courses and play after hours.

“Well, as far as friendships go with Jim, you weren’t friends unless Jim wanted to be friends,” Shore reflects. “One thing that struck me that’s odd about Jim is, he would wear bells on his shoes while he ran. It would drive you nuts, and there’s no doubt in my mind that he did that on purpose to basically get into other people’s heads. And it did.”

The lightning incident

Something in Hogue changed when, the summer after Hogue’s first year at the University of Wyoming, Hogue and Mark worked for a professor catching butterflies and moths in Rocky National Park in Fort Collins, Colorado. While trekking the jagged rocks and taking in the picturesque views of the Rocky Mountains, the duo were caught in a lighting storm. Hogue, usually fearless and strong, was visibly shaken, according to Mark.

“I think Jim thought he was invincible. What happened that day, even if he won’t admit it, is that he realized he was a mortal just like the rest of us,” Mark says resignedly. “We all have that potential: good and evil, right and wrong. It wasn’t acceptable to me that Jim Hogue chose the wrong path because he wanted to do the wrong thing. That was unacceptable to my brain and I used the event at Rocky National Park as a crutch and excuse for me. I don’t know if it was the chicken or the egg, but I knew that the event happened and that he was never the same after that.”

After the “lightning incident,” Mark and Hogue had a falling out, and stopped talking. Despite this, Mark adamantly says that Hogue was a big influence and inspiration for him.

“Jim said ‘Look you may be the smartest guy in your field, and you know eight of them,” Mark says. “‘If you run into someone who knows anything about your topic, don’t talk, just listen because they might know the one or two things that you don’t know. Even if they know one or two things, if it’s the one or two you don’t know, then you’ve gained.”

Like Mark, Moss insists that Hogue was someone with tremendous talent and great potential, but just misled. But, instead of pity, Moss often wonders about Hogue’s path in life had he not been caught by Renee Pacheco.

“Would he have graduated from Princeton and would he be working? A scientist, working on Wall Street, a family man. I don’t know. Probably,” Moss says. “But the structures that supported him, that sustained him, that allowed him to soar at great heights at Princeton — they were taken away. Without that he just had nothing to fall back on. His life has been a downward spiral since then. I don’t think he belongs in prison.”

Ernest Lee & Hogue at Princeton

Ernest Lee, 31-year-old James Hogue’s cross-country teammate when he was at Princeton as the created identity of 19-year-old Alexi Santana, recalls a time when Hogue named all the mascots and school colors of obscure high schools in Kansas City, close to where Hogue grew up. His teammate, who was also from Kansas City, would confirm Hogue’s list, and the team would gasp in awe.

“He [his teammate] would say, ‘How do you know all that stuff?’ and he [Hogue] would just shrug his shoulders and say, ‘Oh, I drove through town once,’ to add to his aura that he was this genius that could pick anything up,” Lee says.

Lee, a graduate of Gunn High School and track coach at Gunn for 18 years, describes Hogue as a “weird guy” who didn’t socialize with the Princeton team. Hogue could name the streets and buildings of Lee’s

hometown of Palo Alto from, what Lee thought, just from one drive through. But his peers thought his quirks were because he was slightly older, Lee said. (Santana told Lee that he deferred his application to Princeton a year to take care of his dying mother in Switzerland; in reality, Hogue was finishing a jail sentence in Ohio).

When Hogue was caught by Renee Pacheco, a Paly graduate who recognized him at a Ivy League track meet, all of his peers, including Lee, were shocked.

“I never thought of it as he took an opportunity away from someone else because he was an add on,” Lee says. “You kind of felt, team-wise, he was our No. 2 guy and you didn’t feel betrayed but you felt mostly embarrassed that he was part of the team. Wow, he fooled all of us.”

However, for Lee, there seems to be something more sinister to Hogue’s crimes.

“In some ways, a lot of people cheer him on like “Yeah, you fooled the stuck up Ivy League school,” Lee says. “But [when] he continued to do other stuff like fraud and petty crime, it’s not a practical joke anymore.”

Not long after the Daily Princetonian printed a dramatic headline about Hogue — which ironically overshadowed headlines about the start of the Gulf War — Lee and his Princeton peers stopped talking about Hogue’s infilitration into campus.

“For a lot of us, we didn’t really have the time to dwell in it anymore,” Lee says. “You have your own stuff to do. The way that I actually went through that, I don’t appreciate how really weird it is from the other people who read about it. I think, especially for my teammates, it was just another cool college story and everyone has cool college stories right? This was ours.”