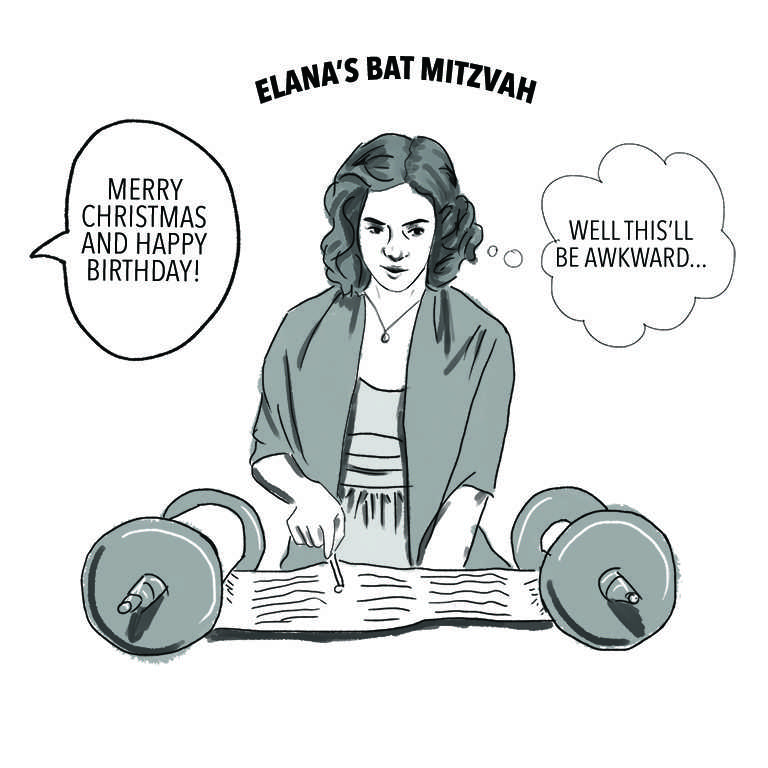

I’m a Jewish Christmas baby — born on Dec. 23, two days before most people celebrate Jesus’ birthday. For as long as I can remember, well-meaning adults have asked me, “Do you get one present for Christmas or two?” Generally, I answer by saying “I’m Jewish” and feel the awkwardness as they stammer through the rest of the conversation, resorting to a stilted, “You get eight presents for Hanukkah? You are so lucky.”

The holiday season, however, is just the beginning of the awkwardness that regularly comes from being a relatively religious Jewish individual in a secular, primarily Christian society. After spending the first nine years of my education at a small Jewish Day School, coming to Palo Alto High School was a big adjustment for me. I had never gone to a school this large before, nor had I gone to a school where the majority of my peers were not Jewish.

Because I was so immersed in that tight-knit environment, when I came to Paly, I quickly noticed just how Christian-centric the school really was. It’s not just that Judaism is barely mentioned, although it barely is. Often, I’ve felt that myself and other non-Christian students are expected to know all about Christian biblical symbols and imagery, but I have not seen the same expectation apply for Christian students with non-Christian imagery. Literature dealing with religions other than Judaism or Christianity, like Islam, Buddhism or Hinduism get even less acknowledgement in the English curriculum.

At first, I was up in arms. I spent my first few years at Paly trying to make everybody else acknowledge that Judaism exists. When many of my peers didn’t know many specifics about Judaism, I was insistent on informing them. I remember seeing a slip of paper summarizing Jewish beliefs in Contemporary World History and being shocked at the the way the worksheet completely confused Jewish ethnic groups and inadequately explained what most Jewish holidays were. I jumped at the chance to correct the worksheet and quickly explained the information to my table group.

After a few such incidents, I grew tired of constantly having to explain things. I obviously didn’t stop being Jewish, but I stopped drawing attention to the inaccuracies that I saw so frequently and rarely mentioned anything about Judaism to my non-Jewish friends. I probably would have stayed that apathetic, until the beginning of the 2015-16 school year. But that’s when I realized that for the first time since I’d started in it, the Palo Alto Unified School District was not giving students the day off of school on Yom Kippur, the most important Jewish holiday of the year.

Annoyed, I offhandedly complained to a few non-Jewish friends, whose reaction shocked me. Most of them weren’t really sure what Yom Kippur was (some asked me if Jews fasted on Ramadan), and even those who did know weren’t aware of the significance of the holiday to Judaism. It took me explaining that Yom Kippur is the holiest day of the year and most Jews spend the day fasting and praying in synagogue for them to understand the significance, but after I did, they agreed with me that the district should have given us the day off.

After this incident, I realized that staying quiet about Judaism was not going to do anything for me. It’s probably the same ignorance to the importance of Yom Kippur in Judaism that led to the district not giving the holiday off in the first place, and if I don’t address that ignorance whenever I see it, I myself am perpetuating the problem.

I do not expect people to immediately know that I’m Jewish, or to know everything about Judaism, but I do want to create a space for my religion. Even in the secular world of Palo Alto, there should be room for me, and for everybody else that isn’t Christian, to practice our religions with respect.