Cherry Ishimatsu still remembers her first day back at Palo Alto High School after the bombing of Pearl Harbor by the Japanese army on Dec. 7, 1941. For Ishimatsu, it was a day full of resentment and awkwardness as her white classmates avoided speaking to her or making eye contact.

“I remember that day so clearly because I could just feel myself sinking slowly down into my seat and I was just in tears,” Ishimatsu says. “I knew that we would be facing a lot of discrimination.”

Weeks after Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s first address, he issued another statement, mandating that Japanese-Americans obey an 8 p.m. curfew and not travel further than a five-mile radius from their home. As Ishimatsu’s house was more th an five miles from Paly, the decree meant the end of her time at school.

“That was when I felt that my citizenship was stripped from me,” Ishimatsu says. “I have not been back at Paly High since.”

Ishimatsu is one of 25 former Paly students, out of a total of 59 Palo Alto Unified School District Japanese-American students who were forcibly detained and incarcerated in high security camps inland on the West Coast during the United States’ involvement in World War II from 1942 to 1945.

With xenophobic sentiments and national security concerns, Roosevelt passed Executive Order 9066 and stripped away the civil rights of thousands of Japanese-Americans. The Supreme Court ruled this act as Constitutional in the 1944 case Fred Korematsu vs. the United States. His daughter, Karen Korematsu, who now runs the Fred Korematsu Institute in his honor, spoke at Paly on Jan. 19.

Although a Federal Court nullified the decision in 1983 due to

misinformation by the Justice Department, the ruling created a legal precedent that still stands today. With the 70-year anniversary of the end of Japanese internment coming up, David Bowers, the mayor of Roanoke, Virginia’s call to intern all Muslim-Americans and Republican Presidential candidate Donald Trump’s support for internment share a disturbing resemblance to Japanese internment.

From Ramona to Racetracks

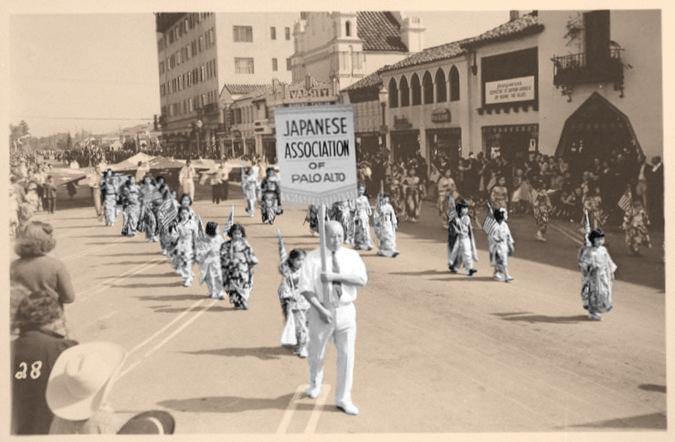

The Japanese-American community in the Bay Area sprang up in the 1890s. In Palo Alto, it manifested as a bustling neighborhood downtown between Emerson and Ramona Street, complete with its own boarding houses and stores.

“Within that three-block radius it was a real self-contained community,” says Pam Hashimoto, daughter of Kiyo Sato, a 1933 graduate of Paly. “It was like being plopped on another planet.”

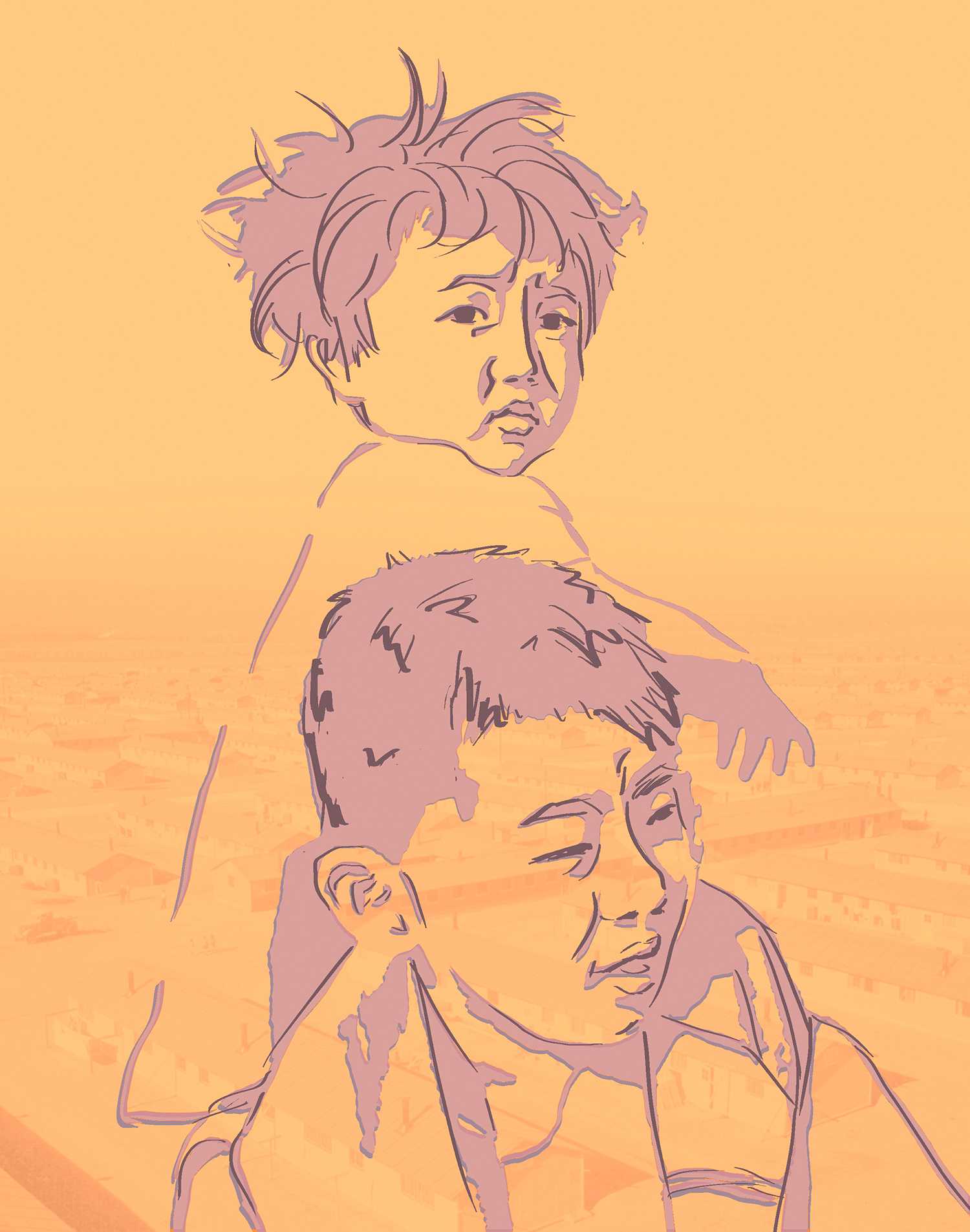

The Issei, or first generation Japanese-Americans, worked largely menial jobs and stayed within their community, not interacting with white Palo Alto residents. However, the Nisei, or second generation, were immersed in both American and Japanese culture, according to Hashimoto.

“That Nisei generation kind of bridged two worlds,” Hashimoto says. “When they went home, they were Japanese, and when they went to school, they were American. They became very adaptable and they did a lot of translation for the parents.”

Kiyo Sato’s family owned a grocery store on Ramona Street while she attended school at Paly. Kiyo kept a diary of her time in Palo Alto starting after her graduation, when she began attending San Jose State. Her sister, Riyo, painted the image of the tree that hangs in the Tower Building.

Kiyo was a social butterfly, often staying out past midnight at local Japanese league events after working shifts in her parents’ grocery store. However, no matter how social she was, Kiyo, like most Nisei, still remained within Japanese social circles.

“All their friendships seemed to be in the Japanese-American community,” Hashimoto says.

Although she did not live on Ramona Street, Ishimatsu still remembers the strong divide and lack of integration between Japanese-Americans and the white community of Palo Alto, even at Paly. Despite playing violin in the Paly orchestra, Ishimatsu says she was not very involved in the Paly community. Even before the war broke out, she was aware of racial tension in Palo Alto.

“There were discriminations, but it was not open,” Ishimatsu says. “We’ve always been under some kind of discrimination, and as a child, I faced some of them, but it was not something that really affected me that much.”

Their stories are documented by Dr. Robert French, a PAUSD substitute and former teacher and principal who has spent the past several decades of his life collecting stories of Japanese-American internment in Palo Alto, hoping to award diplomas to students who were interned before they could graduate. According to French, the Japanese-American community in Palo Alto was wary of the racism coming its way and emphasized their loyalty to the U.S.

“The Japanese community began doing pro-American things before the war, with the way they dressed and hanging flags,” French says. “They tried so hard to appear American.”

However, their efforts were in vain. On Feb. 19, 1942, the tensions culminated in President Roosevelt’s Executive Order 9066, allowing military commanders to forcibly relocate both citizens and non-citizens. By March 24, Japanese exclusion orders were issued throughout the West Coast, and by May, all Japanese-Americans had been detained in one of the ten relocation camps that dotted the interior of the country, living in ramshackle barracks on barren, unwanted tracts of land.

The Palo Alto Japanese-American community had feared internment for almost four months before the government forced it to relocate. Soyo Okazawa, Paly class of 1933 and a friend of the Sato family, recalls living with her family on Ramona during those months.

“She [Okazawa] said they knew it [internment] was imminent,” Hashimoto says. “As soon as they would find out, it would be such a short time that they wouldn’t have much time to plan, so it was very stressful.”

Others, like the Ishimatsu family, moved inward toward Sacramento before the Executive Order, just days after Roosevelt issued the curfew.

“We were told that if we moved to inland California, we would not be sent to camp,” says Ishimatsu. “So my father decided that we would move all of our belongings and move to the central part of California. We went there, and about two months later, they said everyone has to leave all of California.”

In Palo Alto, the Japanese community numbered 144 people, all of whom reported to the train station to be taken to the Santa Anita racetrack in Arcadia, Calif. In a 1942 edition of The Campanile, student James Sato wrote a piece titled “Evacuee not bitter” in which he bid Paly farewell and spoke of his sacrifice in the name of the U.S.

Japanese-Americans were allowed to bring only what they could carry in two hands to the internment camps. Ishimatsu recalls this as one of the most difficult parts of being interned, as no one knew what they had to bring. In Palo Alto, this meant property was left behind.

“There was kind of a land grab,” Hashimoto says. “People had to sell their possessions for pennies on the dollar because they didn’t have much time.”

She recounts the story of her father’s dog, who her family was forced to leave behind because no one wanted him. The Satos, her mother’s family, fared no better, and had to leave the store behind.

Photographs show the histories of forgotten pasts in bags left abandoned on the curbs of bus stops when the evacuation buses couldn’t fit any more luggage. French remembers a conversation with a friend who witnessed the scene.

“These are kids that people had known at Jordan and Paly, and they had to leave,” French says. “He said there were just tears. These were your friends, and they were being uprooted and sent off to some gosh awful place no one knows.”

The kindness of the Palo Alto community is also remembered by Okazawa, who recalls that religious groups such as the Quakers helped Japanese-Americans on evacuation day by giving them rides and helping to carry belongings.

However, although some in the Palo Alto community may have been kind to the Japanese when they left, there was still a strong undercurrent of racism and fear that affected other communities.

“Many Chinese wore a little button that said ‘I’m Chinese,’” French says. “There were people beaten up because there was such hysteria about the war.”

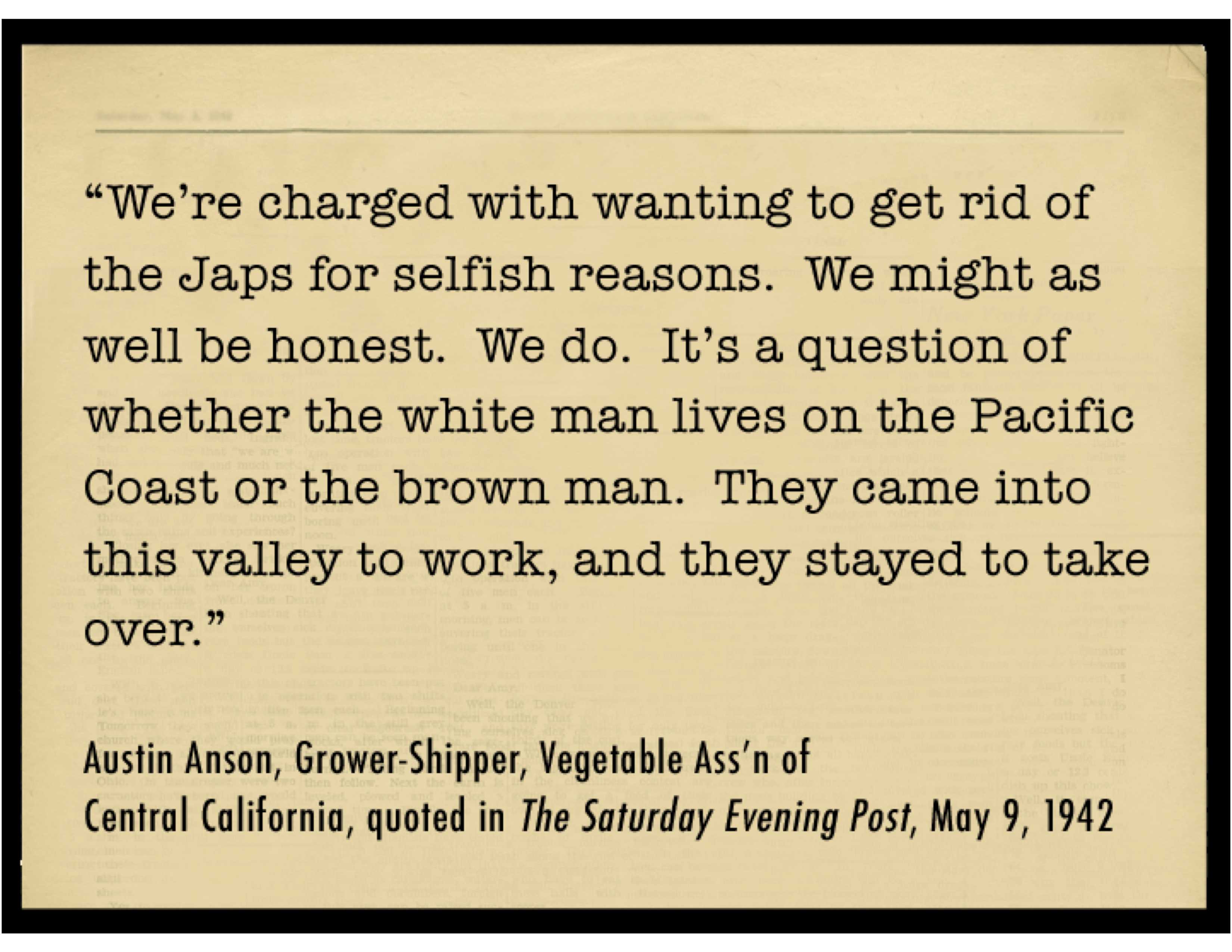

Although the executive order is mostly thought of as being motivated by defense concerns as well as racial tension, historians contend that there was an economic element behind the internment. Hashimoto agrees that internment was partly motivated by economics.

“When you have a small group of a minority and they aren’t considered a threat, you don’t see the prejudice,” Hashimoto says. “When the community starts to get larger in number, when they get organized, they’re seen as a threat. You see that with every minority. They were getting too successful with the nurseries, with the farming and the fisheries, so there was a lot of resentment.”

Paly librarian Rachel Kellerman has assisted in the archiving of Palo Alto’s history. She is working on digitizing the school’s archives and is interested in Japanese-American internment because of what it says about Palo Alto.

“There’s this idea that California has always been a very open and progressive place, but from reading the newspaper archives, there was a strong streak of discrimination that ran through California and our town,” Kellerman says. “It’s really important to go back in time, because the history becomes more alive when it happens in your backyard.”

The Camps

Walking into Tanforan Shopping Center in San Bruno, 30 minutes from Palo Alto, one wouldn’t know that 70 years ago, it was a racetrack, home of the racehorse Seabiscuit. The Seabiscuit statue is hard to miss, as it overshadows the small plaque commemorating the Japanese-American internment which is tucked off to the side, shoved out of the collective memory of the American public.

In 1942, the racetrack served as a transition center on the way east to internment camps for thousands.The Japanese-Americans from San Mateo County went to Tanforan, while those from Santa Clara County went to the Santa Anita. From those centers, Japanese-Americans were sent to residential internment camps further east. Most Palo Altans went to Heart Mountain, Wyo., while others, Okazawa among them, went to separate camps.

“That’s how they broke people up,” Hashimoto says. “Soyo’s husband was a first-year Stanford medical student … so she ended up in Manzanar [Southern California]. When I asked her if she knew anyone there, she said no.”

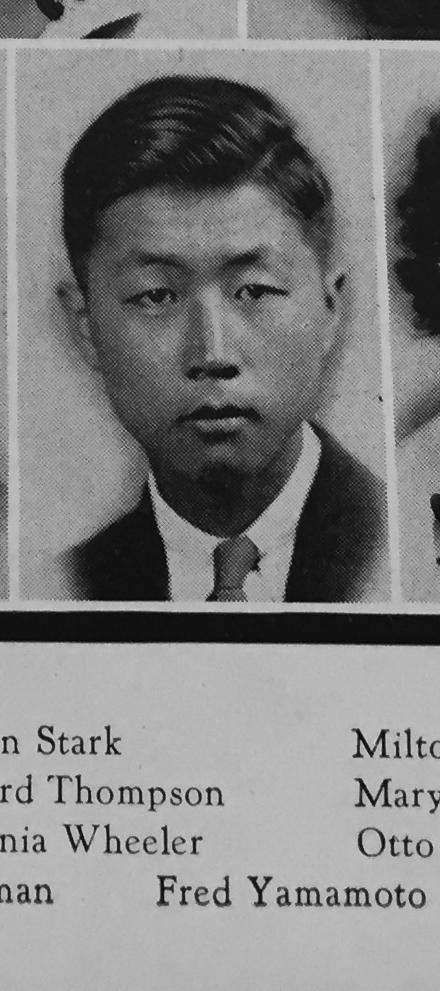

Back: Kiyo, Fred, Tad Tani, Frank Shimada, Henry “Hammy” Hamasaki, Saku Taketa

Front: Riyo, Mary, Jack,, Eldan

Kneeling: Ben Kamada, Frank Furuichi

Because Ishimatsu had moved to Sacramento in an attempt to evade interment, her family was sent to a camp in Jerome, Ark. instead of Heart Mountain like the majority of Palo Alto residents.

“It was a time of doing without many things,” Ishimatsu says. “Everybody had rations to contend with at that time. It was a matter of making do with what we had.”

At the time, Japanese-Americans were initially told they were being interned for their own protection, Ishimatsu recalls that illusion being broken.

“We go to camp and the guns are all turned in towards us,” Ishimatsu says. “If they were protecting us, the guns should have been pointing outside of camp, but they were all pointed inward.”

Even while interned, however, Ishimatsu still recalls how patriotic the Japanese-Americans were.

“There were two kinds of people, but the majority were very patriotic,” Ishimatsu says. “We were all raised in America, we studied American history and we knew more about American history and life than we did of Japan, which was a strange country to us.”

The injustice of the situation was clear to Ishimatsu. One of her most vivid memories is of watching a parade of young Boy and Girl Scouts in the camp.

“I think it was very ironic,” Ishimatsu says. “Here we are, all prisoners behind barbed wire fences and a military guard surrounding us, and here we have young people doing a parade with their American flags flying.”

The Modern Fight for Freedom

With two origami cranes pinned to her shirt and a picture of a bomb exploding stretched across the screen in the Media Arts Center, Karen Korematsu discusses her father’s legacy to a crowd of students and staff at Paly during Tutorial.

Fred Korematsu, an Oakland-born Japanese-American young man, refused to acquiesce to the Japanese internment policy. When he was discovered, arrested and convicted of a federal felony, he opened a case that eventually reached the Supreme Court and that still stands today as one of the many reminders of racial prejudice during times of war.

“Fred Korematsu … really stood up against the government against all odds and really made a difference in the face of challenges from his own community who didn’t want anything to do with him and even his own government,” Karen Korematsu says.

Her father, who was eventually arrested and sent to an internment camp in Topaz, Utah, faced discrimination from both the American public and the Japanese-American community. Other Japanese -American families feared that by associating with him they would be deemed unpatriotic and a threat to security. He was shunned.

“They [the Japanese-American community] decided that my father shouldn’t carry on with his court case,” Karen says. “Well, my father did what my father wanted to do. He just really believed that if he could get all the way to the Supreme Court that they would see that this was wrong.”

Ostracized by his community, Korematsu ate and worked in solitude. Nevertheless, he persevered, bringing his case to the Supreme Court, only to be rebuffed by a vote of six to three.

For the next 30 years of his life, he carried the burden of being a federally-convicted felon, even after the war was distant and his probation was long completed.

“He tried several years later to get his real estate license,” Karen Korematsu says. “Because he wanted to help people who had faced racial discrimination like he did. Because he had [a federal conviction] he was denied his real estate license, and he was really, really hurt.”

In the 1970s and 1980s, the government came under increased scrutiny for its racially charged actions, culminating in the overturning of his conviction in 1983. Lawyers found that the Department of Justice had knowingly misled the Supreme Court to believe that the Japanese-American community posed a much larger threat.

“As the Justice Department and the FBI illustrated, the threat from the Japanese citizenry simply did not exist,” says David Rapaport, Paly U.S. History teacher and a Korematsu Institute partner in education. “The threat was from Japan’s military, based in Japan. There was not a single case of espionage prosecuted on American soil during WWII of a Japanese person.”

Rapaport, who first met Korematsu over 20 years ago, started working with the activist to promote education about the Japanese-American internment in 2013.

“You have to take a stand,” Rapaport says. “You have to be able to speak up when there’s injustice. Karen’s father did that, and he paid the price. Now Karen is building on his legacy to keep the awareness that other groups may experience the same kind of discrimination that her dad did some 70 years ago.”

Coming Home

For the Japanese-American community, coming home was a bittersweet affair. Given only a matter of days to pack up, they had often resorted to leaving their personal property in the hands of their white neighbors.

“They didn’t know what was going to happen,” French says.

Photo by Gabriela Rossner.

At the time Ishimatsu was released, Japanese-Americans weren’t allowed to return to California, so she settled in Chicago as did many other Palo Altans, including the Satos. Once California was re-opened to Japanese-Americans, Ishimatsu still did not return home to Palo Alto.

“We had nothing to come back to,” Ishimatsu says. “So there was no reason for us to come back.”

The end of the war did not signify the end of anti-Japanese sentiment, however,.The archives are littered with accounts of Japanese-Americans being denied the ability to buy property, as well as being treated poorly by fellow Palo Altans.

For Fred Korematsu, his return also came with a stigma within the Japanese-American community. Today hailed as a civil rights hero, he never once spoke with his daughter during her childhood about what had happened to him and the Japanese-American community during the war.

“I found out when I was 16 in history class,” Karen Korematsu says. “I didn’t believe it. My father never talked about it. That was the culture.”

Lessons From History

The reluctance to discuss Japanese internment was not limited to the Japanese-American community and Fred Korematsu. Rapaport recalls a fellow student in his high school English class asking why it wasn’t being taught. His teacher replied that it would make the U.S. look bad.

“When this gal talked about her father’s story not being represented in the high school history book, that created an awareness for me that has never left,” Rapaport says.

Rapaport resolved to spread awareness through his teaching, recording interviews with prominent civil rights activists and partnering with the Korematsu Institute.

“I see my role as an ambassador to spread the philosophy of social justice that the foundation represents,” Rapaport says. “I try to have as much direct contact with students and important and influential people who have worked for social justice. I take a lot of pride in being able to continue their [activists’] stories.”

Kellerman also hopes to keep the stories of Japanese-Americans alive. The digitization of the archives, which includes everything from editions of the Campaniles from the 1930s to the latest Verde, is key.

“What I think is really important about reading archives and listening to people from the time period is to be able to draw your own conclusions about it, and then to be able to place that behavior in the context of the larger world,” Kellerman says. “That builds a lot of insight and empathy.”

While Japanese-American incarceration may seem largely irrelevant, many believe that history has a way of repeating itself. Korematsu informed the Paly crowd that she was dismayed to hear the rhetoric surrounding refugees and the Muslim-American community.

“When I heard the Mayor of Roanoke, Va. make the statement about rounding up Syrian refugees and referring to President Roosevelt’s Executive Order 9066, which totally has been discredited, then you think, ‘Well, here you have a person who is an elected official who obviously didn’t learn lessons of history and we’ve got a long ways to go in education,’” Korematsu says. “Clearly when you see and hear adults make these outrageous mistakes and really points of total racial discrimination then it’s like, ‘Well okay I’ve got a reason to keep on going.’”

Education, Korematsu believes, is key to ensuring that history doesn’t repeat itself. Her father’s later years and her life have been spent trying to teach Americans about the lessons of Japanese-American internment, with varying success.

“My father always believed in education,” Korematsu says. “He crisscrossed the United States and spoke to young people like you and organizations because he didn’t want something like the Japanese-American incarceration to happen again. He felt like education was one of the key ways to prevent that, hopefully. We come very close to making the same mistakes because it seems like people are very short-minded.”

One of the ways by which Korematsu hopes to spread awareness and education is with Fred Korematsu Day, a day she hopes becomes nationally recognized. Fred Korematsu Day, which falls on Jan. 30, her father’s birthday, is currently recognized in six states. On Saturday Jan. 30 in San Francisco, community members and esteemed guests gathered to commemorate Korematsu. As part of the event, a panel of high school students from Oakland Tech High School, Castlemont High School and Paly spoke with California Supreme Court Justice Mariano-Florentino Cuéllar about racism. Paly junior Sean Romeo was especially touched by the opportunity.

“There were a lot of amazing, important people discussing this issue [internment] and how it ties to bigotry and racism and all sorts of issues today, so I was really glad to be offered this opportunity,” Romeo says. “There were so many different kinds of perspectives on all sorts of issues that matter to us today that relate to what Mr. Korematsu stood for.”

Born in Japan to a Japanese mother and American father, the story of internment is something that Romeo has strived to learn more about. As a student in Rapaport’s U.S. History class, he has taken advantage of any opportunity to educate himself about Japanese-American internment, including attending the presentation by Korematsu at Paly.

“We don’t really bother to learn about things that make us uncomfortable and that we’re not really familiar with,” Romeo says. “If we can make a discussion out of what’s happening, I think that would be really great for the future.”

Although it has been 70 years since her internment, the events that Ishimatsu witnessed and lived still continue to shape her life. Even though her memories remain with her, she has lived her life trying to let go of the past while simultaneously trying to make the best out of what she is given

“If I do that [resent America], I’ll always be angry, and there’s no advantage to being angry over something that happened,” Ishimatsu says. “I’ve made the most of my life after that. I always made sure that they [my children] didn’t face what I had faced, because I didn’t want any discrimination of any kind rearing its head at my children. I felt I had already paid for that.”